India Discovered (23 page)

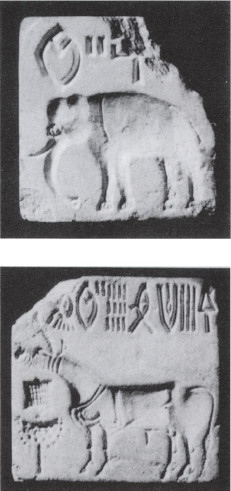

To the discovery of India’s past was added a proto-historical dimension with the twentieth century excavation of an urban civilization dating from 2500 – 1500 BC. The ‘Harappan’ or ‘Indus Valley’ culture, although widespread and highly sophisticated (witness the statuette of a ‘dancing girl’), is likely to remain somewhat enigmatic until the pictographic script (as found on steatite seals, can be read.

If our poets had sung them [wrote Havell of the Rajput palaces], our painters pictured them, our heroes and famous men had lived in them, their romantic beauty would be on every man’s lips in Europe. Libraries of architectural treatises would have been written on them.

Bishop Heber had been equally impressed when he toured the palace of Amber a century earlier.

I have seen many royal palaces containing larger and more stately rooms – many the architecture of which was in purer taste, and some which have covered a greater extent of ground – but for varied and picturesque effect, for richness of carving, for wild beauty of situation, for the number and romantic singularity of the apartments, and the strangeness of finding such a building in such a place, I am unable to compare anything with Amber&. The idea of an enchanted castle occurred, I believe, to all of us, and I could not help thinking what magnificent use Ariosto or Sir Walter Scott would have made of such a building.

Even Fergusson was not blind to the romantic appeal of the Rajput palaces. He praised their settings and lack of affectation. But there was no room for them in his scheme of things.

There are some twenty or thirty royal residences in central India, all of which have points of interest and beauty; some for their extent, others for their locality, but every one of which would require a volume to describe in detail.

He contented himself with a description of only the more obvious examples – Gwalior, Amber, Udaipur and Dig – and could only mention the two great palaces of Orchha

and Datia. Havell went into more detail, noting the way these buildings seemed to grow organically out of the rocks on which they stood ‘without self-conscious striving after effect’. Thus, above all, their romantic appeal; but there is also a grandeur and an elegance of detail beside which the Moghul palaces pale into mere prettiness. Here was Hindu architecture both more virile and more noble than

its Islamic equivalent.

Sir Edwin Lutyens, the architect of New Delhi, thought the palace of Datia one of the most architecturally interesting buildings in India. It is also one of the most impressive. Conceived as a single unit, unlike the Moghul palaces, it towers above the little town of Datia like the work of an extinct race of giants. Each side is about 100 yards long and rises from the

bare rock so subtly that it is hard to tell where nature’s work ends and man’s begins. The impression is of immense strength, and only the skyline of flattened domes and cupolas gives any hint of the treasures within. There, the first two storeys are dark and cool, hot weather retreats; then suddenly one emerges into the light and a fairyland of pillared walkways, verandahs and pavilions. Paintings

and mosaics adorn the walls, and the verandahs are screened with several hundred feet of the most intricately fretted stone windows.

Datia was built by Rajah Bir Singh Deo in the seventeenth century. The palaces of Orchha were also his work, and here there are more painted halls and dappled pavilions as well as some of the finest carved brackets. But in this case the setting is one of ruination

– miles of crumbling stables, overgrown gardens and forgotten temples. Somehow it seems more in keeping with these now forlorn masterpieces. Several thousand people a day visit the Moghul palaces of Delhi and Agra; scarcely a single soul disturbs the rats and the bats at Datia and Orchha. Havell’s rhapsodies and Lutyens’ admiration have changed nothing. It says much for the formative and lasting

character of James Fergusson’s work that they have yet to find their true place in the scheme of India’s monuments.

CHAPTER TEN

A Subject of Frequent Remark

Sixty miles west of Datia and Gwalior, the long hill fortress of Narwar rises in shaggy scarps above scrubland. A neat white village nestles against its flank, from whence a broad path, paved with slabs of red sandstone, winds up the hill. The steps are shallow enough for cavalry to clatter up and down, and the cusped gateway at the top is big enough to

admit an elephant. Today, only one leaf of the great studded door remains, leaning out precariously from a single hinge. The stately flight of steps beyond is spattered with cow dung, and vegetation sprouts from every crack in the stonework. To left and right on the level summit a scene of bewildering devastation unfolds. Trees grow through the masonry of nameless halls, their roots lifting the stone

floors. A row of pillars leans sideways, like dominoes frozen in fall. In the prickly undergrowth a hole, no bigger than a rabbit’s, reveals vaulted chambers black with bats. And in a sun-filled pavilion projecting out from the cliff-top, where the last of the mirror-work mosaic is flaking from the stucco, herdsmen bivouac amongst their flocks, the smoke of their fire blackening the painted ceiling,

fragments of mirror-work crunching underfoot.

Narwar was a Rajput palace in the sixteenth century, and became one of the six great strongholds of the Moghuls in the seventeenth. It reverted to the Rajputs in the eighteenth, and was still in use at the end of the century. But by the time Cunningham visited it in 1864, it was deserted, with the vegetation already in control. Today, its interest

lies in the fact that nothing much has ever been done to preserve it: it remains much as it was 100 years ago. Real ruins, those that have escaped the attentions of the archaeologist and the conservationist, have a special appeal. The past seems to cling more closely to them. At Narwar nature, and not tourism, has taken over. Lizards scuttle across the white marble of the royal bathrooms, and a vulture

poses, wings draped, on the highest cupola. Here, away from the manicured lawns and the two rupees admission charge, one senses the romantic beauty of sheer desolation and the very real excitement of archaeological discovery.

In the nineteenth century the neglected state of sites like Narwar was the rule rather than the exception. Thomas Twining, the young man who was privileged to dine with

Sir William and Lady Jones in Calcutta, visited Agra and Delhi in the 1790s.

As we advanced [into Delhi] the ruins became more thickly scattered around us, and at length covered the country on every side as far as the eye could see. Houses, palaces, tombs, in different stages of delapidation, composed the striking scene. The desert we had passed was cheerful compared with the view of desolation now before us. After traversing ruined streets without a single inhabitant for a mile, I saw a large mausoleum at a short distance on our right. I made my way over the ruins towards it with a few of my soldiers, leaving the rest of my people on the road. Dismounting and ascending some steps, I came upon a large square terrace flanked with minarets, and having in the centre a beautiful mausoleum surmounted by an elegant dome of white marble. I had seen nothing so beautiful except the Taje Mehal. It was in vain to look about for someone to gratify my curiosity. The once most populous and splendid city of the East now afforded no human being to inform me what king or prince had received this costly sepulchre&. But the name of ‘Humayun’ in Persian letters of black marble, which chance or respect had preserved untouched, made it probable that this was the tomb of this excellent monarch.

It was indeed the tomb of Humayun, son of Babur and second of the Great Moghuls. But so little cherished was this masterpiece of Moghul architecture, then only 300 years old, that even its identity had become a matter of conjecture.

Within a decade of Twining’s visit the British were established in

Delhi. This in itself was no guarantee of a more enlightened policy towards ancient monuments. But the Islamic monuments of Agra and Delhi were safe enough from the terrible depredations of the railway contractors. Their varying fortunes in the nineteenth century had far more to do with swings in official policy.

At first the British Resident and his staff in Delhi were much in awe of their surroundings.

The ruins of all those old Delhis-Indraprastha, the Qutb, Tughlakabad, Ferozabad – were poignant reminders of the transitory nature of dominion. Even in Shahjehanabad (the Old Delhi of today) the signs of decay were already there. A Moghul emperor still lived in the Red Fort, the court ritual was still minutely observed. But the reality of power and the sources of wealth had passed away.

The imperial treasury was being milked by several hundred dependent relatives and favourites; the palace itself was becoming a shanty town for all these scroungers. In 1825 Bishop Heber found the Diwan-i-Am, the colonnaded audience hall, choked with lumber, and the imperial throne so deep in pigeon droppings that its mosaics were scarcely visible. Pipal trees were sprouting from the walls of the

little Pearl Mosque and in the Diwan-i-Khas, or private audience chamber, half the precious stones in the floral inlays had been prised from their white marble setting. ‘All was desolate, dirty and forlorn’, and in the formal gardens ‘the bath and fountain were dry, the inlaid pavement hid with lumber and gardener’s sweepings, and the walls stained with the dung of birds and bats’.

The Bishop’s

next port of call was Agra. As he approached the city he passed by the massive tomb of Akbar at Sikandra, ‘the most splendid building in its way that I have seen in India’. Unlike the other Moghul tombs, Akbar’s has no central dome and consists of five diminishing storeys bristling with little domed

chattris.

Fergusson, pursuing his theory that Akbar alone adopted Indian architectural styles,

would suggest that it derived from the lay-out of a Buddhist monastery. Its other distinguishing feature is a colossal gateway with towering minarets at each of its four corners. According to Twining the top sections of all these minarets had snapped off ‘having been struck and thrown down by lightning’; but by the time of Heber’s visit money had been granted for repairs and an officer of Engineers

was already on site.

The 1820s saw the first spurt of energy in this direction, and in Delhi, too, efforts were being made to restore some of the more important buildings. As Garrison Engineer between 1822 and 1830, Major Robert Smith was the man chiefly responsible. He was an artist of repute and a great admirer of Moghul architecture. One of his first assignments was to repair the Jama Masjid,

the great mosque built by Shah Jehan. Its skyline is one of the most dramatic in India and it was the massive dome that, according to a contemporary, most needed Smith’s services.

The dome had several trees growing out of the joinings in the stones, and parts of the back wall had fallen down, and had been taken away by some heathen Hindoo to make himself a tenement; this part was also repaired. Major Smith is particularly well qualified for the charge of restoring such magnificent relics of art, as much by his exquisite judgement and taste in the style of the works, as his acknowledged professional talents, which place him amongst the foremost of his compeers.

No doubt emboldened by this success, Smith moved on to the Qutb Minar. But here, inexplicably, that ‘exquisite taste and judgement’

seemed to desert him. In 1803 the building had been seriously damaged by an earthquake: some of the balustrades were shaken loose, the main doorway collapsed and, worst of all, the crowning cupola fell off. Smith’s job, as well as clearing and landscaping the whole site, was to make good this damage. A sketch that had appeared in an early number of the Asiatic Society’s Journal purported

to show the original cupola; Smith rejected this as too much like ‘a large stone harp’. Instead, he produced his own design – an octagonal stone pavilion, above the dome of which there was to be a smaller wooden cupola and on top of this a short flagstaff.

The work had barely started when Bishop Heber visited the site and delivered his oft quoted dictum ‘These Pathans built like giants and finished

their work like jewellers.’ (He was wrong of course: the builders of the Qutb were not Pathans; the giants were Turks and the jewellers Indians.) But by 1829 Smith’s work was finished and was immediately greeted by a storm of protest. ‘A silly ornament like a parachute, which adds nothing to the beauty of the structure,’ thought one observer. According to another, the pavilion made the whole

thing look top heavy and the wooden cupola was like ‘an umbrella of Chinese form’. The Governor-General was more upset about the flagstaff, ‘an innovation which whether viewed as a matter of taste, or with reference to the feelings of the Moghul court or population of Delhi, has little to recommend it’.

Smith hit back. The emperor liked the flagstaff, especially since his own flag was flown from

it. As for the pavilion, there was no telling precisely what the original had looked like. Moreover, the whole tower was a hotch-potch of inconsistencies, having been built by three different sovereigns and already extensively repaired. His design for the pavilion and cupola was wholly authentic – very similar to the decorative arrangements found on the roof of the nearby tomb of Safdar Jang.