Indigo (31 page)

Authors: Clemens J. Setz

(Source not ascertainable)

3.

The Man with the Lightbulb Head

[GREEN FOLDER]

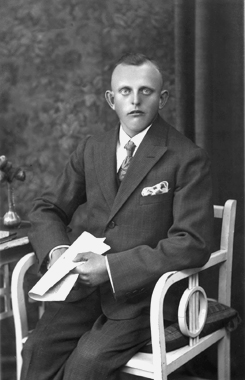

Charles Alistair Adam Ferenz-Hollereith, Jr., lived from 1946 to 2003. He was the son of Luisa Ferenzi and Adam Hollereith, who emigrated in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War from Switzerland to the United States. (The

i

in Luisa's surname was collected as a customs duty, so to speak, by an American official on their arrival.) He was born in Boston. Until his death from three strokes in relatively close succession, he was a White House advisor on safety and health issues, previously he had worked for several decades at the CIA. The photo on his Wikipedia page shows a man with a strangely lightbulb-shaped face, a quaint shock of hair that sprouts like a medieval helmet plume from the middle of his head, and a slightly perplexed-looking expression. Although the picture, according to the caption, was taken in 1963, it seems older, as if it came from another era. This impression of an existence slightly displaced in time and history was in fact defining and characteristic of the life of Dr. Ferenz-Hollereith. Of many people it is said that they were ahead of their time. That definitely does not apply to Ferenz-Hollereith. He lived to a great extent in the past, was a man of the fifties through and through, a time that in the United States brought forth a joy in medical experimentation that was completely novel in style and character, yes, it's safe to say, an entirely new spirit began to waft at that time through the psychiatric clinics and military hospitals. This spirit wafted directly from the past into the present, basically it was a sort of whirlwind, which did not so much drive things further in a particular direction as it made them revolve around themselves, in ever narrowing orbits: the scenes of systematic destruction and murder discovered and documented in the concentration camps liberated by the Allied forces, the Nazi doctors later treated with awe and dread, who were brought to America and were there to do essentially only one thing, that is, to talk, report, describe, the mysterious pioneering spirit that flared up in experiments with darkness and sensory deprivationâa snowstorm of new ideas pulling at the edges of the psyche. From this emerged, somewhat belatedly, after a time lag, Charles Ferenz-Hollereith. He wrote his dissertation on Walter Freeman, and many regard this paper as an attempted rehabilitation of that controversial physician, who has gone down in history as father of the modern icepick lobotomy. Shortly after Ferenz-Hollereith began working at the CIA, he apparently specialized (at least according to Zone [1994] and Helman [2003], Helman even presents some documentary evidence) in examining outdated medical experiments for their scientific content, their usability, and perhaps even their repeatability. An example: In the forties and fifties, huge numbers of cats, dogs, and monkeys were fed LSD and observed coping with disorientation, rapidly increasing panic, and disturbed motor activity. Shortly thereafter, these experiments were repeated with human test subjects, mainly soldiers who had volunteered. Ferenz-Hollereith wonderedâor, as Zone portrays it, received from his superiors the order to wonderâwhether the original animal experiments could perhaps be used to clear up other matters of scientific dispute. In the original series of experiments, something might have been overlooked.

So much for the fruits of the three-hour phone call with Oliver Baumherr. During the conversation Julia came into the room several times. Once she put a hand on my shoulder from behind and left it there until I jerked forward because Herr Baumherr had been saying something incredibly interesting. When I turned around, she was no longer standing behind me. I heard the apartment door close.

As we were saying goodbye, Oliver Baumherr invited me to visit him in Vienna. He had read my articles back then with great interest.

Subway Wind

On the train to Vienna I listened for two hours to the wild

Studies for Player Piano

by Conlon Nancarrow, which really woke me up and gave me self-confidence. Then I took the U1 toward Karlsplatz. The subway announced itself by the characteristic tunnel wind, an oddly meaningless movement of air, which smells and tastes the same in all metropolises of the world. Years ago I had read in an article that the loose hair swept by the tunnel wind from the heads of the people waiting on the platform collects over the years in the tunnel, in the strangest and most inaccessible places, and now and then bursts forth again and rolls along as a gossamer phantom train in front of the real train. In the nineties, huge hairballs had to be removed from the London Underground, which would have hindered the smooth running of the trains, and during the inspections they had also discovered nests, large enough even for a curled-up person, which had presumably been built by tunnel rats inspired by the oversupply of soft and ideally supple nesting material to construct these baroque dwellings. An entrance to a disused side passage or safety tunnel had been clogged by a sort of spider web of interwoven human hair, and the workers almost hadn't managed to remove it. And then there had, of course, also been the homeless man named Fred, for several days his picture had filled the newspapers, a person residing for years in the galleries off the large connecting tunnel, who had made himself a cap out of the hair flying everywhere through the air. This had later been stolen from him by a journalist, it was said, and it actually resurfaced not long after in a dubious auction house, albeit described incorrectly or with intent to deceive as a healing artifact of an extinct nomadic tribe from Niger.

On the phone Julia was a bit disgusted by my improvised description of a gigantic hairball, which had flown through the tunnel, directly past us. But she also laughed and asked what shape it had been.

â Like the Apollo 11 lunar module, I said.

She advised me not to listen to so much Nancarrow when traveling, that crazy music just made me unnecessarily high. Before I could ask how she knew what I had been listening to, she hung up.

APUIP

The man who opened the door for me was quite small and seemed squat and compact in an almost moving way. Immediately I developed a strong urge to pick him up, carefully roll him, and push him through a circular opening; the skin of his face looked as if made to be touched.

Oliver Baumherr was chairman of an organization with a bizarre name: Association for the Peaceful Use of Indigo Potential. Oftenâto Baumherr's chagrinâthe name was altered to Association for the Peaceful Use of Indigo Children, he told me. Yes, now that I heard it, I realized that I had come across that phrase before, somewhere, in a magazine article.

When I mentioned this memory to him, he pulled a sheet of paper toward himself and picked up a pen.

â What article was that?

â I don't remember.

â Was it by that wretched Häusler-Zinnbret?

â I'm sorry, I really can't recall.

â But you can check for me?

I had to think for a while about how to respond to that. It was clear that I had touched a sore spot.

â No, I don't think so. I wouldn't know where to look for it.

â Was it in print? In a book? Or on the Internet?

I shrugged.

â But people usually remember the medium at least. Because if it were in a book, for example,

I

could even name the author for you, for there aren't that many to choose from, I couldâ

â I don't remember. Really.

He seemed to return a bit to reality, only a single step separated him from the present situation: he and I, in his Vienna apartment, on Walfischgasse 12 in the first district. It was Monday, five o'clock in the evening. (In Graz I hadn't been able to get out of school early.) Oliver Baumherr had at first stood opposite me in a bathrobe, had immediately apologized for how he was dressed, and had disappeared for several minutes. He had come back in a tracksuit, as might be worn to go jogging. He had asked whether I would like tea, and I had said yes. But after twenty minutes of conversation, he had apparently forgotten the tea. I had trouble imagining the management of an association in the hands of this obviously disorganized man.

â When did you found your association? I asked, to steer the conversation in another direction.

He drummed the pen on the blank sheet of paper that lay between us, sucked air through his teeth, and leaned back.

â It's not easy, he said. For me. And for the others. You have to understand that, Herr Setz.

I nodded.

â You don't know what it's like when you're met with hostility from all sides because of a cause you've devoted yourself to. It's terrible what happens to them, you know? Absolutely terrible, awful, horrible, you can't . . . well, you can't even imagine it.

â To the I . . . to the children?

â Yes.

â What happens to them?

He put down his pen. He pursed his lips, then he said:

â You know, I hadn't expected you to ask about Ferenz on the phone. That's never happened to me before. You were at Helianau?

â Yes.

â For how long?

â I was actually supposed to be there for six months, but then I had a . . . falling-out with the principal there.

â Glad to hear it.

He nodded gravely as he said that.

â Ferenz is not simply a person, that is . . . to begin with, he was, of course. But I told you about Dr. Ferenz-Hollereith to test your reaction. That's all. Nowadays it's more a principle. A principle that is upheld by several people. In their eyes Ferenz is something special. An artist, so to speak.

Oliver Baumherr licked his lips and looked up at the chandelier that hung over our heads.

â But he's dead now, isn't he?

â Not the principle. But the person Ferenz-Hollereith, he is dead. Well and truly dead.

â Is he actually the inventor of the so-called Hollereith treatment? I asked.

Oliver Baumherr clicked his tongue.

â Ah, total nonsense, the Hollereith treatment is a myth. Those sweat cures, with which you are toughened for . . . what do I know, the financial world, life, toughness, a secret society, what do I know? Nonsense, Internet chatter. Just like those MKUltra projects in the United States, which basically only constitute a platform for schizophrenics and recognition-seekers, who imagine that the government trained them in their childhood to be murderers.

I waited for him to go on.

â You're not even protesting, he said.

â Should I be?

â But how long were you going to let me babble on like that?

â For a long time. And I would have taken everything down.

He laughed and clapped.

â Touché, touché, hahaha! Very good.

He rubbed his hands together and reflected. Then he laughed again and said:

â What would you have done if I had said the same thing about the Holocaust, that it's all just a myth, gas chambers never really existed, and so on?

â I probably also would have taken notes and . . . and maybe asked whether I had understood you correctly.

â No, no, no, it doesn't work like that, he said. You can't do that, that's cowardly. You're not here to take notes, after all, a dictation machine could do that better than you. I can fill a MiniDisc with babble for you and send it to you. It doesn't work like that.

I didn't know how to respond.

â How do you feel now? he asked. Like a cornered rat?

â No. I think you're right. I probably would have protested eventually.

â Eventually! Ah, that's easy to say in hindsight, of course. But you were at Helianau. Didn't you take notice there of . . .

â Of?

â Sweat cures.

â Yes, that is, no, I didn't see it directly, but Frau Dr. Häuslâ

â Ah, said Oliver Baumherr, not that name! Terrible!

â She mentioned it, anyway.

â Awful woman. Doesn't have the slightest idea.

â About what?

Oliver Baumherr shook his head, and I again felt like kneading his pleasant roundness. Then he said:

â Have you seen that video that is ubiquitous . . . of that elephant painting flowers?

â What? No.

â Well, you see some elephant, somewhere in Thailand. In a Thailand zoo, to be precise. It has a brush in its trunk and is painting a picture on a canvas with it. Of an elephant with a flower in its trunk. And then of a flower. And again a flower. Wait, I'll show it to you.

â I think I actually have seen it, I lied.

â Okay, but do you also know how that's done? Is this elephant all right, or is it tortured until it has mastered this trick? Everything okay?

â Oh . . . yeah, I just feel . . . a bit dizzy. The long train ride.

â Would you like a glass of water?

â Yes, please.

Oliver Baumherr got me a glass and put it down in front of me.

â What we know about the relocated children is more than what is known about this elephant. They are well treated. Relatively speaking, at least. They're provided for, they aren't tortured, they're merely planted in a particular group that is to be destabilized. What do I know, in a school, for example, which is located next to a strategically important building. Or in a prison camp. There they sit in a room next to the cells. The adjacent room itself is beautifully furnished. Their parents are nearby. Usually they even move with them.