Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation (43 page)

Read Indonesia, Etc.: Exploring the Improbable Nation Online

Authors: Elizabeth Pisani

Once a year, Rimba families spend one day clearing land in the forest. They hack trees down with an axe, burn off the remaining scrub to fertilize the soil and plant cassava, sweet-potatoes and other staples. Much of the rest of the diet comes from hunting (frogs, fish, bears and many other animals besides). When we were ordering food at a nasi Padang place in the trans town, I suggested chicken. Gentar stuck out his tongue in disgust: no real Rimba will eat an animal that has been raised by man, he said. The Rimba gather plants and roots to eat, as well as honey, rattan and wild rubber to sell. As transmigrants and plantation workers began to seep into the lands that were once Rimba territory, the market for these products grew and the Rimba began to ‘know money’, a period Mijak dates from the mid-1990s.

Cash from wild rubber meant that people could buy chainsaws, and that made nonsense of the rules through which the Rimba had always restricted deforestation: overnight, the amount of land a family could clear in a day increased by over tenfold. More cleared land also meant the Rimba could plant rubber trees and generate more cash. And when it’s planted with rubber, the cleared forest does not revert to jungle as it used to when families used small plots for rice and vegetables for just a year or two before moving on.

Rubber equals cash equals chainsaws equals more rubber and more cash, equals a motorbike to get between market and new plantation more easily, equals more time in town, thus rice, sugar and cheezy potato snacks in rainbow packages as well as petrol and rubber seedlings, so more need for cash, so more trees cut and rubber planted, and so it goes around.

Gentar filched a cooking pot from the abandoned camp and we wandered on through the forest a bit until we hit a river. With astounding efficiency, he snapped a few twigs into a perfect campfire – Mijak sat tidily on a plastic bag and watched – and soon we were lunching on instant noodles, brought in from the trans town.

After that, it was time for a siesta. We climbed up into someone’s ‘house’. The open bamboo platform stood at about chest height. Beneath it hung a chainsaw. At one end of the platform sat a big cardboard carton that until recently held a television set. Bits of broken styrofoam were strewn on the forest floor around the hut. I pointed to the carton and raised my eyebrow, questioning. ‘It’s a TV’, Gentar said flatly. Watched with what electricity? ‘A generator’.

Gentar’s wife told me later that when Gentar was away in Jakarta, leaving her bikeless, she and the three kids had spent six hours walking from their forest camp down to the plantation where I met them. ‘Like the old days,’ she said. Now that nearly everyone had motorbikes, she said, things were much easier. But if motorbikes are followed by television sets and generators, it seems to me that moving about will soon be more difficult than ever. If the rubber prices stay high, consumerism might put an end to the nomadic life even before deforestation does.

On the long drive home through the plantation, I spotted one tree standing majestically high above the dreary spikes of the oil palms. Small wooden pegs stuck out at intervals up its trunk. ‘Our honey tree,’ said Gentar. For generations, bees have congregated in particular trees, yielding small-celled forest honeycomb which the Rimba collect in a quasi-religious ritual. The community had protected the tree when the chainsaws came. But: ‘The bees don’t want to go there any more. There’s nothing for them around here.’

After dark, Mijak and I lolled around in our little shelter, talking of the future. Mijak said his goal was to achieve secure land rights, ‘so that the Rimba can continue to live in the forest according to their adat’. I asked if that’s what he really wanted, to live in the forest. ‘That’s different,’ he shot back. ‘I’m Muslim now. My private hopes are something separate.’

Gentar padded over to join us as Mijak unfolded his private dreams. First, he would go to an organic-farming school run by a friend of Butet’s in Java. He’d buy a couple of hectares of land, not too far from Gentar’s, and put them under rubber as security for his children. Then he would go to college and study law. In his second year, he would get married ‘but not to a Rimba girl. Firstly, we’d have different religions, and secondly, I already know how the world works and she wouldn’t know anything . . .’ Gentar and I were already pulling faces, but Mijak was not done with his plans. ‘Then we’ll have two children, first a boy, then a girl, and then . . .’

Gentar shrieked with laughter. ‘Wah, first a boy, then a girl. Why did you need to go and get a religion? You’ve already become God . . .!’

Gentar had promised his own parents that he would never leave the forest or the Rimba way of life. And so it has been. He married the girl from the tree next door, hunts frogs at night, and is one of the most infectiously happy people I have ever met. Not in an unthinking, Noble Savage sort of way. More in a considered, what-more-do-I-need? way.

He is acutely aware of the threat to his lifestyle posed both by the annihilation of the forest on the one hand and the excessive zeal of what he calls the ‘tree-loving NGOs’ on the other. But for now he can still play with his children, tease his friends and sell his rubber. ‘I saw those people in Jakarta just sitting in their cars all day,’ he said. ‘How is that better than sitting under a tree?’

As we left the forest, Mijak asked me what month it was. In speech, many Indonesians just refer to the months by their numbers. Month five, I said. Right, he said. Then: ‘Does that mean June?’ No, it’s May. ‘Ah.’ Pause. ‘So what comes after May?’ This young man who can quote Conservation Law 5/1990 and Spatial Planning Law 26/2007 but who was raised in a world where time is marked off as durian season or honey season, could not list the months in order.

In theory, the NGO that Mijak and his friends have set up to defend the rights of his fellow Rimba should allow him to plant one clean-sneakered foot in the world of cappuccinos, land titles and ‘civilized’ religion, while keeping the other, muddier foot in the world of frog-hunting and bear dinners. But it does not seem likely that the world of Bapak Seribu and his Forest Terminators can coexist for long with that of the Rimba and their honey trees. Mijak can only defend the Rimba’s traditional way of life if he fights his battles by rules determined out in The Light. To do that successfully, he has to fit into that world himself, he must blend into modern Indonesia, where there’s no longer any room for the Rimba cosmology.

When we met his headman in the forest, Mijak had shown him every respect. Afterwards, though, he had grown despondent. ‘The elders talk on and on about adat,’ said Mijak. ‘But they don’t realize that Rimba adat is worthless out there in The Light.’

I sympathized with Mijak as he tried to coexist in very different worlds. My atheist, divorced, unemployed, itinerant reality presented no problem when I was in Jakarta. But in other parts of the country, I had to smooth those things away if I wanted to be accepted into people’s homes and lives. For months now, I had been lying about myself dozens of times a day. I was on long leave from the Ministry of Health. I lived in Jakarta with an Indonesian husband who worked in the private sector, a Muslim. I was a practising Catholic; my husband and I respected one another’s faiths, and it didn’t pose too many problems because we had no kids.

My childlessness was the only thing about the made-up me that was entirely true. I knew it would cause comment, but I hadn’t guessed how much. From the fat woman in the jilbab I’d get: ‘What do you mean, no kids? You mean not yet.’ Then, after a look at the wisps of white at my temples. ‘How old are you?’ Then someone with a pock-marked face would butt in: ‘Where have you been for treatment? You should go to Singapore, they can do anything in Singapore!’ An elbow to pockmark’s ribs: ‘No, wait, she should meet my cousin, he has a special medicine. Three women in the village got pregnant after he gave them the special treatment.’

From the men: ‘What do you mean, no kids? Why don’t you go out and get one?’ Some thin, wolfish man would narrow his eyes. ‘I suppose your husband has left you, has he? How many children does he have with his younger wife?’

I can’t tell people that I’ve never wanted kids. That would

definitely

not be acceptable. So I respond by looking self-pitying, pious and mystified all at the same time. I point heavenwards, indicate that they should ask the Good Lord why I have not been graced with offspring, and shrug to show that I am resigned to my fate. Still, it gets wearing, having your ovaries interrogated by strangers day after day. About a week after emerging from the Rimba’s devastated forests, I was having breakfast in Tanjung Pandan, the main town in Belitung, a tin-producing island off the east coast of Sumatra. It’s a prosperous town of Chinese shop-houses and colonial-era bungalows. From the photo on the wall, I judged that the coffee shop I was in had not changed since it was established in the 1940s.

The owner, dressed in nylon shorts, a string vest, plastic sandals – the uniform of Chinese traders when they are just minding the shop – was counting grubby 1,000 rupiah notes into the drawer of a teak desk. He welcomed me to sit with him and his friends, and we ran through the script. ‘

Dari mana?

’: Where are you from? ‘Wah, Inggris, Manchester United! But your Indonesian is so good. Where is your husband from? . . .’ When we got to the ‘How many kids?’ it just popped out of my mouth: ‘Two. They’re already grown up,’ and the conversation moved on. I kicked myself for not having invented children months earlier.

After his friends left, the coffee shop owner introduced himself as Ishak Holidi, a member of the local parliament. The coffee shop is a family business and a good place to keep in touch with what people are thinking and talking about, he said. We talked for a couple of hours about local government, investment in education, political accountability, policies to reduce dependence on mining. The next morning, when I went in for breakfast, Pak Ishak was dressed for work. He waved me over. ‘We’re celebrities now,’ he laughed. He handed me the local newspaper. There we were, he and I, grinning stupidly at someone’s camera phone, over a headline that read ‘FOREIGN VISITOR PRONOUNCES BELITUNG CAKES DELICIOUS’. And in the story: ‘Elizabeth, mother of two . . .’

My non-existent children caused me other headaches too. With men, they put a full stop to the fertility question quite quickly. But women expected my children to have names, genders, ages, occupations, whole back stories of their own. It proved to be a lot of effort and I soon went back to being childless.

*

This is a good example of the misunderstandings that may arise because of the vagaries of Indonesian, which often dispenses with the subject of a verb. Mijak actually said: ‘Second, don’t know how.’ I have inferred the ‘they’, but he could equally have meant ‘we’. He used both in talking of his own tribe, depending on the circumstance.

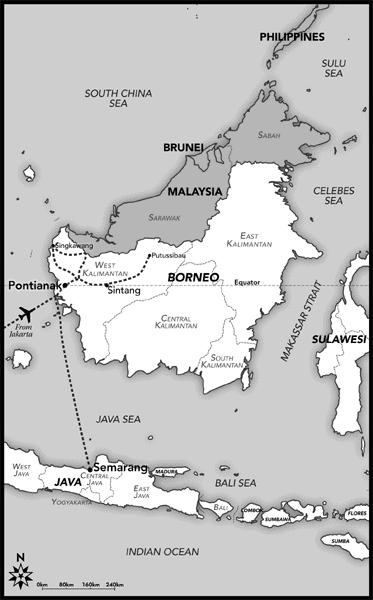

Map K: K

ALIMANTAN

(B

ORNEO

)

Miss Equator stood ramrod straight in the blazing midday sun, sweat trailing in rivulets down her powdered face. Balanced precariously on her head was a large silver globe shot through with an arrow. It was a styrofoam-and-tinfoil replica of the monument that towered above her.

After another brief pit-stop in Jakarta, I had flown to Pontianak, the largest city in West Kalimantan and the only city in the world that sits exactly on the equator, and it was the day of the autumn equinox, the day when, as the sun reaches its zenith, people’s shadows disappear. At the equator monument, built by the Dutch in 1908 and massively expanded by a proud local government only recently, gaggles of visitors to the equinox festival jostled forward to have their photos taken with the shadowless beauty queen.

The Mayor of Pontianak attended the festivities wearing a pearl-grey silk outfit, his waistcloth positively stiff with gold thread; his wife’s sarong was embroidered to match. They were protected from the sun by a giant umbrella twirled overhead by a batik-clad flunky, and looked for all the world like a pre-colonial era Sultan and his wife.