Influence: Science and Practice (10 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Reciprocal Concessions

There is a second way to employ the reciprocity rule to get someone to comply with a request. It is more subtle than the direct route of providing that person with a favor and then asking for one in return, yet in some ways it is much more effective. A personal experience I had a few years ago gave me firsthand evidence of just how well this compliance technique works.

I was walking down the street when I was approached by an 11- or 12-year-old boy. He introduced himself and said he was selling tickets to the annual Boy Scouts Circus to be held on the upcoming Saturday night. He asked if I wished to buy any tickets at $5 apiece. Since one of the last places I wanted to spend Saturday evening was with the Boy Scouts, I declined. “Well,” he said, if you don’t want to buy any tickets, how about buying some of our chocolate bars? They’re only $1 each.” I bought a couple and, right away, realized that something noteworthy had happened. I knew that to be the case because (a) I do not like chocolate bars; (b) I do like dollars; (c) I was standing there with two of his chocolate bars; and (d) he was walking away with two of my dollars.

READER’S REPORT 2.3

From a State of Oregon Employee

The person who used to have my job told me during my training that I would like working for my boss because he is a very nice and generous person. She said that he always gave her flowers and other gifts on different occasions. She decided to stop working because she was going to have a child and wanted to stay home; otherwise I am sure she would have stayed on at this job for many more years.

I have been working for this same boss for six years now, and I have experienced the same thing. He gives me and my son gifts for Christmas and gives me presents on my birthday. It has been over two years since I have reached the top of my classification for a salary increase. There is no promotion for the type of job I have and my only choice is to take a test with the state system and reapply to move to another department or maybe find another job in a private company. But I find myself resisting trying to find another job or move to another department. My boss is reaching retirement age and I am thinking maybe I will be able to move out after he retires because for now I feel obligated to stay since he has been so nice to me.

Author’s note:

I am struck by this reader’s language in describing her current employment options, saying that she “will be able” to move to another job only after her boss retires. It seems that his small kindnesses have nurtured a binding sense of obligation that has made her unable to seek a better paying position. There is an obvious lesson here for managers wishing to instill loyalty in employees. But there is a larger lesson for all of us, as well: Little things are not always little—not when they link to the big rules of life, like reciprocity.

To try to understand precisely what had happened, I went to my office and called a meeting of my research assistants. In discussing the situation, we began to see how the reciprocity rule was implicated in my compliance with the request to buy the candy bars. The general rule says that a person who acts in a certain way toward us is entitled to a similar return action. We have already seen that one consequence of the rule is an obligation to repay favors we have received. Another consequence of the rule, however, is an obligation to make a concession to someone who has made a concession to us. As my research group thought about it, we realized

that was exactly the position the Boy Scout had put me in. His request that I purchase some $1 chocolate bars had been put in the form of a concession on his part; it was presented as a retreat from his request that I buy some $5 tickets. If I were to live up to the dictates of the reciprocation rule, there had to be a concession on my part. As we have seen, there was such a concession: I changed from noncompliant to compliant when he moved from a larger to a smaller request, even though I was not really interested in

either

of the things he offered.

It was a classic example of the way a weapon of influence can infuse a compliance request with its power. I had been moved to buy something, not because of any favorable feelings toward the item, but because the purchase request had been presented in a way that drew force from the reciprocity rule. It had not mattered that I do not like chocolate bars; the Boy Scout had made a concession to me,

click

, and

whirr

, I responded with a concession of my own. Of course, the tendency to reciprocate with a concession is not so strong that it will work in all instances on all people; none of the weapons of influence considered in this book is that strong. However, in my exchange with the Boy Scout, the tendency had been sufficiently powerful to leave me in mystified possession of a pair of unwanted and overpriced candy bars.

Why should I feel obliged to reciprocate a concession? The answer rests once again in the benefit of such a tendency to the society. It is in the interest of any human group to have its members working together toward the achievement of common goals. However, in many social interactions the participants begin with requirements and demands that are unacceptable to one another. Thus, the society must arrange to have these initial, incompatible desires set aside for the sake of socially beneficial cooperation. This is accomplished through procedures that promote compromise. Mutual concession is one important such procedure.

The reciprocation rule brings about mutual concession in two ways. The first is obvious; it pressures the recipient of an already-made concession to respond in kind. The second, while not so obvious, is pivotally important. Because of a recipient’s obligation to reciprocate, people are freed to make the

initial

concession and, thereby, to begin the beneficial process of exchange. After all, if there were no social obligation to reciprocate a concession, who would want to make the first sacrifice? To do so would be to risk giving up something and getting nothing back. However, with the rule in effect, we can feel safe making the first sacrifice to our partner, who is obligated to offer a return sacrifice.

Rejection-Then-Retreat

Because the rule for reciprocation governs the compromise process, it is possible to use an initial concession as part of a highly effective compliance technique. The technique is a simple one that we will call the rejection-then-retreat technique, although it is also known as the door-in-the-face technique. Suppose you want me to agree to a certain request. One way to increase the chances that I will comply is first to make a larger request of me, one that I will most likely turn down. Then, after I have refused, you make the smaller request that you were really interested in all along. Provided that you structured your requests skillfully, I should view your second request as a concession to me and should feel inclined to respond with a concession of my own—compliance with your second request.

Was that the way the Boy Scout got me to buy his candy bars? Was his retreat from the $5 request to the $1 request an artificial one that was intentionally designed to sell candy bars? As one who has still refused to discard even his first Scout merit badge, I genuinely hope not. Whether or not the large-request-then-small-request sequence was planned, its effect was the same. It worked! Because it works, the rejection-then-retreat technique can and will be used

purposely

by certain people to get their way. First let’s examine how this tactic can be used as a reliable compliance device. Later we will see how it is already being used. Finally we can turn to a pair of little-known features of the technique that make it one of the most influential compliance tactics available.

Remember that after my encounter with the Boy Scout, I called my research assistants together to try to understand what had happened to me—and, as it turned out, to eat the evidence. Actually, we did more than that. We designed an experiment to test the effectiveness of the procedure of moving to a desired request after a larger preliminary request had been refused. We had two purposes in conducting the experiment. First, we wanted to see whether this procedure worked on people besides me. (It certainly seemed that the tactic had been effective on me earlier in the day, but then I have a history of falling for compliance tricks of all sorts.) So the question remained, “Does the rejection-then-retreat technique work on enough people to make it a useful procedure for gaining compliance?” If so, it would definitely be something to be aware of in the future. Our second reason for doing the study was to determine how powerful a compliance device the technique was. Could it bring about compliance with a genuinely sizable request? In other words, did the

smaller

request to which the requester retreated have to be a

small

request? If our thinking about what caused the technique to be effective was correct, the second request did not actually have to be small; it only had to be smaller than the initial one. It was our suspicion that the critical aspect of a requester’s retreat from a larger to a smaller favor was its appearance as a concession. So the second request could be an objectively large one—as long as it was smaller than the first request– and the technique would still work.

After a bit of thought, we decided to try the technique on a request that we felt few people would agree to perform. Posing as representatives of the “County Youth Counseling Program,” we approached college students walking on campus and asked if they would be willing to chaperon a group of juvenile delinquents on a day trip to the zoo. This idea of being responsible for a group of juvenile delinquents of unspecified age for hours in a public place without pay was hardly an inviting one for these students. As we expected, the great majority (83 percent) refused. Yet we obtained very different results from a similar sample of college students who were asked the very same question with one difference. Before we invited them to serve as unpaid chaperons on the zoo trip, we asked them for an even larger favor—to spend two hours per week as counselors to juvenile delinquents for a minimum of two years. It was only after they refused this extreme request, as all did, that we made the small, zoo-trip request. But presenting the zoo trip as a retreat from our initial request, our success rate increased dramatically. Three times as many of the students approached in this manner volunteered to serve as zoo chaperons (Cialdini, Vincent, Lewis, Catalan, Wheeler, & Darby, 1975).

Be assured that any strategy able to triple the percentage of compliance with a substantial request (from 17 to 50 percent in our experiment) will be used often in a variety of natural settings. Labor negotiators, for instance, often use the tactic of making extreme demands that they do not expect to win but from which they can retreat and draw real concessions from the opposing side. It would appear, then, that the procedure would be more effective the larger the initial request, since there would be more room available for illusory concessions. This is true only up to a point, however. Research conducted at BarIlan University in Israel on the rejection-then-retreat technique shows that if the first set of demands is so extreme as to be seen as unreasonable, the tactic backfires (Schwarzwald, Raz, & Zvibel, 1979). In such cases, the party who has made the extreme first request is not seen to be bargaining in good faith. Any subsequent retreat from that wholly unrealistic initial position is not viewed as a genuine concession and, thus, is not reciprocated. The truly gifted negotiator, then, is one whose initial position is exaggerated just enough to allow for a series of small reciprocal concessions and counteroffers that will yield a desirable final offer from the opponent (Thompson, 1990).

I witnessed another form of the rejection-then-retreat technique in my investigations of door-to-door sales operations. These organizations used a less engineered, more opportunistic version of the tactic. Of course, the most important goal for a door-to-door salesperson is to make the sale. However, the training programs of each of the companies I investigated emphasized that a second important goal was to obtain from prospects the names of referrals—friends, relatives, or neighbors, on whom the salesperson could call. For a variety of reasons, which we will discuss in

Chapter 5

, the percentage of successful door-to-door sales increases impressively when the sales representative is able to mention the name of a familiar person who “recommended” the sales visit.

Never as a sales trainee was I taught to get the sales pitch refused so that I could then retreat to a request for referrals. In several such programs, though, I was trained to take advantage of the opportunity to secure referrals offered by a customer’s purchase refusal: “Well, if it is your feeling that a fine set of encyclopedias is not right for you at this time, perhaps you could help me by giving me the names of some others who might wish to take advantage of our company’s great offer. What would be the names of some of these people you know?” Many individuals who would not otherwise subject their friends to a high-pressure sales presentation do agree to supply referrals when the request is presented as a concession from a purchase request they have just refused.

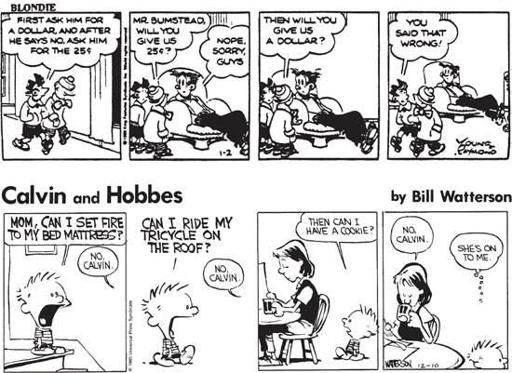

Right and Wrong Ways to Use the Rejection-Then-Retreat Tactic

The extreme request has to go first, and it can’t be too extreme.

Blondie reprinted with permission of King Features Syndicate, Inc.; Calvin and Hobbes, copyright © 1985 by Bill Watterson. Distributed by Universal Press Syndicate. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.