Influence: Science and Practice (30 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

Still another fascinating prediction flows from Phillips’ idea. If the increase in wrecks following suicide stories truly represents a set of copycat deaths, then the imitators should be most likely to copy the suicides of people who are similar to them. The principle of social proof states that we use information about the way others have behaved to help us determine proper conduct for ourselves. As the campus-charity-request experiment showed, we are most influenced in this fashion by the actions of people who are like us.

Therefore, Phillips reasoned, if the principle of social proof is behind the phenomenon, there should be some clear similarity between the victim of the highly publicized suicide and those who cause subsequent wrecks. Realizing that the clearest test of this possibility would come from the records of automobile crashes involving a single car and a lone driver, Phillips compared the age of the suicide-story victim with the ages of the lone drivers killed in single-car crashes immediately after the story appeared in print. Once again the predictions were strikingly accurate: When the newspaper detailed the suicide of a young person, it was young drivers who then piled their cars into trees, poles, and embankments with fatal results; but when the news story concerned an older person’s suicide, older drivers died in such crashes (Phillips, 1980).

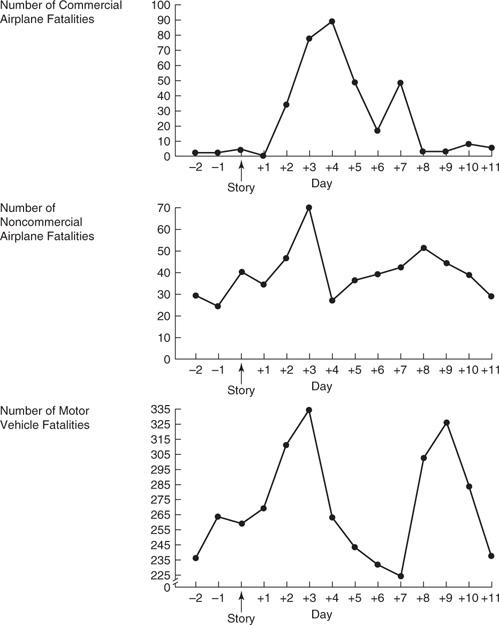

This last statistic is the clincher for me. I am left wholly convinced and, simultaneously, wholly amazed by it. Evidently, the principle of social proof is so wide-ranging and powerful that its domain extends to the fundamental decision for life or death. Phillips’ findings illustrate a distressing tendency for suicide publicity to motivate certain people who are similar to the victim to kill themselves—because they now find the idea of suicide more legitimate. Truly frightening are the data indicating that many innocent people die in the bargain (see

Figure 4.2

).

Figure 4.2

Daily Fluctuation in Number of Accident Fatalities before, on, and after Suicide Story Date

As is apparent from these graphs, the greatest danger exists three to four days following the news story’s publication. After a brief drop-off, there comes another peak approximately one week later. By the eleventh day, there is no hint of an effect. This pattern across various types of data indicates something noteworthy about secret suicides. Those who try to disguise their imitative self-destruction as accidents wait a few days before committing the act—perhaps to build their courage, to plan the incident, or to put their affairs in order. Whatever the reason for the regularity of this pattern, we know that travelers’ safety is most severely jeopardized three to four days after a suicide-murder story and then again, but to a lesser degree, a few days later. We would be well advised, then, to take special care in our travels at these times.

As if the frightening features of Phillips’ suicide data weren’t enough, his additional research (Phillips, 1983) brings more cause for alarm: Homicides in this country have a simulated, copycat character after highly publicized acts of violence. Heavyweight championship prize fights that receive coverage on network evening news appear to produce measurable increases in the United States homicide rate. This analysis of heavyweight championship fights (between 1973 and 1978) is perhaps most compelling in its demonstration of the remarkably specific nature of the imitative aggression that is generated. When such a match was lost by a black fighter, the homicide rate during the following 10 days rose significantly for young black male victims but not young white males. On the other hand, when a white fighter lost a match, it was young white men, but not young black men, who were killed more frequently in the next 10 days. When these results are combined with the parallel findings in Phillips’ suicide data, it is clear that widely publicized aggression has the nasty tendency to spread to similar victims, no matter whether the aggression is inflicted on the self or on another.

Perhaps nowhere are we brought into more dramatic contact with the unsettling side of the principle of social proof than in the realm of copycat crime. Back in the 1970s, our attention was brought to the phenomenon in the form of airplane hijackings, which seemed to spread like airborne viruses. In the 1980s, our focus shifted to product tamperings, such as the famous cases of Tylenol capsules injected with cyanide and Gerber baby food products laced with glass. According to FBI forensic experts, each nationally publicized incident of this sort spawned an average of 30 more incidents (Toufexis, 1993). More recently, we’ve been jolted by the specter of contagious mass murders, occurring first in workplace settings and then, incredibly, in the schools of our nation. For instance, immediately following the bloody rampage by two Littleton, Colorado, high-school students on April 20, 1999, police responded to scores of similar threats, plots, and attempts by troubled students. Two of those attempts proved “successful”: A 14-year-old in Taber, Alberta, and a 15-year-old in Conyers, Georgia, killed or wounded a total of eight classmates within 10 days of the Littleton massacre. In the week following the horrendous murder-suicide attack at Virginia Tech University in April of 2007, newspapers across the country reported more murder-suicide incidents of their own, including 3 in Houston alone (Ruiz, Glenn, & Crowe, 2007). It is instructive that after the Virginia Tech massacre, the next such event of similar magnitude occurred not at a high school, but also at a university, Northern Illinois.

Events of this magnitude demand analysis and explanation. Some common thread needs to be identified to make sense of it all. In the case of the workplace murders, observers noticed how often the killing fields were the backrooms of U.S. post offices. So, the finger of blame was pointed at the “intolerable strains” of the U.S. postal environment. As for the school-based slaughter, commentators remarked on an odd commonality: All the affected schools were located in rural or suburban communities rather than in the ever-simmering cauldrons of inner-city neighborhoods. So, the media instructed us as to the “intolerable strains” of growing up in small town or suburban America. By these accounts, the stressors of U.S. post office environments and of small town American life created the explosive reactions of those who worked and lived there. The explanation is straightforward: Similar social conditions beget similar responses.

Malfunctioning Copier

Five minutes before the start of school on May 20, 1999, 15-year-old Thomas (“TJ”) Solomon opened fire on his classmates, shooting six of them before he was stopped by a heroic teacher. In struggling to comprehend the underlying causes, we must recognize the effect on him of the publicity surrounding a year-long string of similar incidents—first in Jonesboro, Arkansas, then in Springfield Oregon, then in Littleton, Colorado, and then, just two days earlier, in Taber, Alberta. As one of his friends declared in response to the question of why distraught students were suddenly turning murderous at school, “Kids like TJ are seeing it and hearing it all the time now. It’s like the new way out for them” (Cohen, 1999).

But you and I have been down the “similar social conditions” road before in trying to understand anomalous patterns of fatalities. Recall how Phillips (1979) considered the possibility that a set of common social conditions in a particular environment might explain a rash of suicides there? It wasn’t a satisfactory explanation for the suicides; and I don’t think it is a satisfactory account for the murder sprees, either. Let’s see if we can locate a better alternative by first trying to regain contact with reality: The “intolerable strains” of working at the post office or of living in rural/suburban America!? Compared to working in the coal mines or compared to living on the gang-ruled, mean streets of inner cities? Come on. Certainly the environments where the mass slaying occurred have their tensions. But they appear no more severe (and often appear less severe) than many other environments where such incidents have not taken place. No, the similar social conditions theory doesn’t offer a plausible account.

Then what does? I’d nod right at the principle of social proof, which asserts that people, especially when they are unsure of themselves, follow the lead of similar others. Who is more similar to a disgruntled postal employee than another disgruntled postal employee? And who is more similar to troubled small town American teenagers than other troubled small town American teenagers? It is a regrettable constant of modern life that many people live their lives in psychological pain. How they deal with the pain depends on numerous factors, one of which is a recognition of how others

just like them

have chosen to deal with it. As we saw in Phillips’ data, a highly publicized suicide prompts copycat suicides from similar others—from

copies

of the cat. I believe the same can be said for a highly publicized multiple murder. As is the case for suicide stories, media officials need to think deeply about how and how prominently to present reports of killing sprees. Such reports are not only riveting, sensational, and newsworthy, they are malignant.

Monkey Island

Work like Phillips’ helps us appreciate the awesome influence of the behavior of similar others. Once the enormity of that force is recognized, it becomes possible to understand perhaps the most spectacular act of compliance of our time—the mass suicide at Jonestown, Guyana. Certain crucial features of the event deserve review.

The People’s Temple was a cultlike organization that was based in San Francisco and drew its recruits from the poor of that city. In 1977, the Reverend Jim Jones—who was the group’s undisputed political, social, and spiritual leader—moved the bulk of the membership with him to a jungle settlement in Guyana, South America. There, the People’s Temple existed in relative obscurity until November 18, 1978, when Congressmen Leo R. Ryan of California (who had gone to Guyana to investigate the cult), three members of Ryan’s fact-finding party, and a cult defector were murdered as they tried to leave Jonestown by plane. Convinced that he would be arrested and implicated in the killings and that the demise of the People’s Temple would result, Jones sought to control the end of the Temple in his own way. He gathered the entire community around him and issued a call for each person’s death to be done in a unified act of self-destruction.

The first response was that of a young woman who calmly approached the now famous vat of strawberry-flavored poison, administered one dose to her baby, one to herself, and then sat down in a field, where she and her child died in convulsions within four minutes. Others followed steadily in turn. Although a handful of Jonestowners escaped and a few others are reported to have resisted, the survivors claim that the great majority of the 910 people who died did so in an orderly, willful fashion.

News of the event shocked the world. The broadcast media and the papers provided a barrage of reports, updates, and analyses. For days, conversations were full of the topic, “How many have they found dead now?” “A guy who escaped said they were drinking the poison like they were hypnotized or something.”“What were they doing down in South America, anyway?” “It’s so hard to believe. What caused it?”

Yes, “What caused it?”—the critical question. How are we to account for this most astounding of compliant acts? Various explanations have been offered. Some have focused on the charisma of Jim Jones, a man whose style allowed him to be loved like a savior, trusted like a father, and treated like an emperor. Other explanations have pointed to the kind of people who were attracted to the People’s Temple. They were mostly poor and uneducated individuals who were willing to give up their freedoms of thought and action for the safety of a place where all decisions would be made for them. Still other explanations have emphasized the quasi-religious nature of the People’s Temple, in which unquestioned faith in the cult’s leader was assigned highest priority.

No doubt each of these features of Jonestown has merit in explaining what happened there, but I do not find them sufficient. After all, the world abounds with cults populated by dependent people who are led by a charismatic figure. What’s more, there has never been a shortage of this combination of circumstances in the past. Yet virtually nowhere do we find evidence of an event even approximating the Jonestown incident among such groups. There must be something else that was critical.