Influence: Science and Practice (45 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

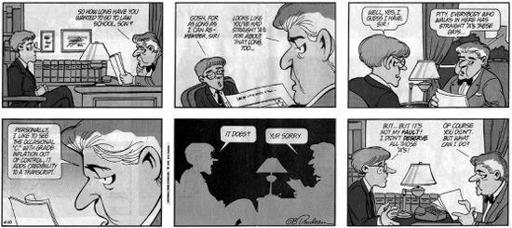

Doonesbury/Gary Trudeau

A Spoonful of Medicine Makes the Sugar Go Down

Besides its capacity to combat the perception of grade inflation, a weakness can become a strength in a variety of other situations. For example, one study found that letters of recommendation sent to the personnel directors of major corporations produced the most favorable results for job candidates when the letters contained one unflattering comment about the candidate in an otherwise wholly positive set of specific remarks (Knouse, 1983).

DOONESBURY

© 1994 G.B. Trudeau. Reprinted with permission of UNIVERSAL PRESS SYNDICATE. All rights reserved.

I have seen this approach used with remarkable effect in a place that few of us recognize as a compliance setting—a restaurant. It is no secret that, because of shamelessly low wages, servers in restaurants must supplement their earnings with tips. Leaving the

sine qua non

of good service aside, the most successful waiters and waitresses know certain tricks for increasing tips. They also know that the larger a customer’s bill, the larger the amount of money they are likely to receive in a standard gratuity. In these two regards, then—building the size of the customer’s charge and building the percentage of that charge that is given as a tip—servers regularly act as compliance agents.

Hoping to find out how they operate, I applied for a position as a waiter at several fairly expensive restaurants. Without experience, though, the best I could do was to land a busboy job that, as things turned out, provided me a propitious vantage point from which to watch and analyze the action. Before long, I realized what the other employees already knew: that the most successful waiter in the place was Vincent who somehow arranged for patrons to order more and tip higher. The other servers were not even close to him in weekly earnings.

So I began to linger in my duties around Vincent’s tables to observe his technique. I quickly learned that his style was to have no single style. He had a repertoire of approaches, each ready to be used under the appropriate circumstances. When the customers were a family, he was effervescent—even slightly clownish—directing his remarks as often to the children as the adults. With a young couple on a date, he became formal and a bit imperious in an attempt to intimidate the young man (to whom he spoke exclusively) into ordering and tipping lavishly. With an older, married couple, he retained the formality but dropped the superior air in favor of a respectful orientation to both members of the couple. Should the patron be dining alone, Vincent selected a friendly demeanor—cordial, conversational, and warm.

Vincent reserved the trick of seeming to argue against his own interests for large parties of 8 to 12 people. His technique was veined with genius. When it was time for the first person, normally a woman, to order, he went into his act. No matter what she elected, Vincent reacted identically: His brow furrowed, his hand hovered above his order pad, and after looking quickly over his shoulder for the manager, he leaned conspiratorially toward the table to report for all to hear “I’m afraid that is not as good tonight as it normally is. Might I recommend instead the ___ or the ___?” (At this point, Vincent suggested a pair of menu items that were slightly less expensive than the dish the patron had selected initially.) “They are both excellent tonight.”

With this single maneuver, Vincent engaged several important principles of influence. First, even those who did not take his suggestions felt that Vincent had done them a favor by offering valuable information to help them order. Everyone felt grateful, and consequently, the rule for reciprocity would work in his favor when it came time for them to decide on his gratuity. Besides hiking the percentage of his tip, Vincent’s maneuver also placed him in a favorable position to increase the size of the party’s order. It established him as an authority on the current stores of the house: he clearly knew what was and wasn’t good that night. More-over—and here is where seeming to argue against his own interests comes in—it proved him to be a trustworthy informant because he recommended dishes that were slightly

less

expensive than the one originally ordered. Rather than trying to line his own pockets, he seemed to have the customers’ best interests at heart.

To all appearances, he was at once knowledgeable and honest, a combination that gave him great credibility. Vincent was quick to exploit the advantage of this credible image. When the party had finished giving their food orders, he would say, “Very well, and would you like me to suggest or select wine to go with your meals?” As I watched the scene repeated almost nightly, there was a notable consistency to the customer’s reaction—smiles, nods, and, for the most part, general assent.

Even from my vantage point, I could read their thoughts from their faces. “Sure,” the customers seemed to say, “You know what’s good here, and you’re obviously on our side. Tell us what to get.” Looking pleased, Vincent, who did know his vintages, would respond with some excellent (and costly) choices. He was similarly persuasive when it came time for dessert decisions. Patrons who otherwise would have passed up the dessert course or shared with a friend were swayed to partake fully by Vincent’s rapturous descriptions of the baked Alaska and chocolate mousse. Who, after all, is more believable than a demonstrated expert of proven sincerity?

READER’S REPORT 6.3

From a Former CEO of a Fortune 500 Company

In a business school class I developed for aspiring CEOs, I teach the practice of acknowledging failure as a way to advance one’s career. One of my former students has taken the lesson to heart by making his role in a dot-com company failure a prominent part of his résumé—detailing on paper what he learned from the experience. Before, he tried to bury the failure, which generated no real career success. Since, he has been selected for multiple prestigious positions.

Author’s note:

This strategy of taking due responsibility for a failure doesn’t just work for individuals within an organization. It appears to work for the organizations themselves. Research shows that companies that take blame for poor outcomes in annual reports have higher stock prices one year later than companies that don’t take blame for poor outcomes (Lee, Peterson, & Tiedens, 2004).

By combining the factors of reciprocity and credible authority into a single, elegant maneuver, Vincent was able to inflate substantially both the percentage of his tip and the base charge on which it was figured. His proceeds from this trick were handsome indeed. Notice, though, that much of his profit came from an apparent lack of concern for personal profit. Seeming to argue against his financial interests served those interests extremely well.

Summary

In the Milgram studies of obedience we can see evidence of strong pressure in our society for compliance with the requests of an authority. Acting contrary to their own preferences, many normal, psychologically healthy individuals were willing to deliver dangerous and severe levels of pain to another person because they were directed to do so by an authority figure. The strength of this tendency to obey legitimate authorities comes from systematic socialization practices designed to instill in members of society the perception that such obedience constitutes correct conduct. In addition, it is frequently adaptive to obey the dictates of genuine authorities because such individuals usually possess high levels of knowledge, wisdom, and power. For these reasons, deference to authorities can occur in a mindless fashion as a kind of decision-making shortcut.

When reacting to authority in an automatic fashion, there is a tendency to do so in response to the mere symbols of authority rather than to its substance. Three kinds of symbols that have been shown by research to be effective in this regard are titles, clothing, and automobiles. In separate studies investigating the influence of these symbols, individuals possessing one or another of them (and no other legitimizing credentials) were accorded more deference or obedience by those they encountered. Moreover, in each instance, individuals who deferred or obeyed underestimated the effect of authority pressures on their behaviors.

It is possible to defend ourselves against the detrimental effects of authority influence by asking two questions: Is this authority truly an expert? How truthful can we expect this expert to be? The first question directs our attention away from symbols and toward evidence for authority status. The second advises us to consider not just the expert’s knowledge in the situation but also his or her trustworthiness. With regard to this second consideration, we should be alert to the trust-enhancing tactic in which communicators first provide some mildly negative information about themselves. Through this strategy they create a perception of honesty that makes all subsequent information seem more credible to observers.

Study Questions

Content Mastery

- What, in your opinion, is Milgram’s most persuasive evidence for his argument that the willingness of subjects in his experiments to harm another results from a strong tendency to obey authority figures?

- What does the research indicate about our ability to recognize the influence of authority pressures on our actions? Cite evidence to support your position.

- Which are the three most influential symbols of authority, according to the research discussed in the chapter? Give examples from your own experience of the way you have seen at least two of these symbols work.

Critical Thinking

- In

Chapter 1

, we came across a disturbing phenomenon called

Captainitis

, in which junior members of a flight crew pay no attention to the captain’s errors or are reluctant to mention them. If you were an airplane captain what would you do to reduce this potentially disastrous tendency? - Why do you suppose the relationship between size and status developed as it has in human society? Do you see any reason why this relationship might change in the future? If so, by what processes?

- Suppose you held a position in an advertising agency in which your job was to create a TV commercial for a product that had several good features and one weak feature. If you wanted the audience to believe in the good features, would you mention the weak one? If you did mention it, would you do so at the beginning, middle, or end of the commercial? What is the reason for your choice?

- How does the photograph that opens this chapter reflect the topic of the chapter?