Influence: Science and Practice (53 page)

Read Influence: Science and Practice Online

Authors: Robert B. Cialdini

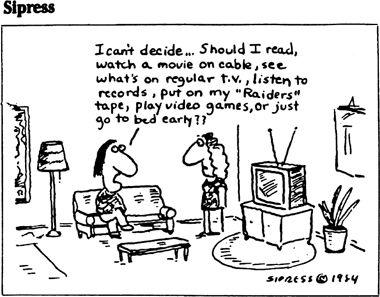

Opting Out of the Options

Too many options can prove wearisome.

©

1984, David Sipress, from Wishful Thinking, © 1987, by Harper and Row

.

Just one decade later,

Time

magazine signaled that Macrae’s future age had arrived by naming a machine, the personal computer, as its Man of the Year.

Time’s

editors defended their choice by citing the consumer “stampede” to purchase small computers and by arguing that “America [and], in a larger perspective, the entire world will never be the same.” Macrae’s vision is presently being realized. Millions of ordinary “duffers” are sitting in front of computers with the potential to present and analyze enough data to bury an Einstein.

Modern day visionaries—like Bill Gates, chairman of Microsoft—agree with Macrae, asserting that we are creating an array of devices capable of delivering a universe of information “to anyone, anywhere, anytime” (Davidson, 1999). But notice something telling: Our modern era, often termed The Information Age, has never been called The Knowledge Age. Information does not translate directly into knowledge. It must first be processed—accessed, absorbed, comprehended, integrated, and retained.

Shortcuts Shall Be Sacred

Because technology can evolve much faster than we can, our natural capacity to process information is likely to be increasingly inadequate to handle the

abundance of change, choice, and challenge that is characteristic of modern life. More and more frequently, we will find ourselves in the position of lower animals—with a mental apparatus that is unequipped to deal thoroughly with the intricacy and richness of the outside environment. Unlike the lower animals, whose cognitive powers have always been relatively deficient, we have created our own deficiency by constructing a radically more complex world. The consequence of our new deficiency is the same as that of the animals’ long-standing one: when making a decision, we will less frequently engage in a fully considered analysis of the total situation. In response to this “paralysis of analysis,” we will revert increasingly to a focus on a single, usually reliable feature of the situation.

2

2

Even trial judges employ this shortcut approach rather than the considered and contemplative one we expect from them. In bail determinations for instance, they are more likely to base their decisions on the earlier choice of a prosecutor, police officer, or prior court than on a more complex analysis that includes factors related to due process (Dhami, 2003).

When those single features are truly reliable, there is nothing inherently wrong with the shortcut approach of narrowed attention and automatic responding to a particular piece of information. The problem comes when something causes the normally trustworthy cues to counsel us poorly, to lead us to erroneous actions and wrongheaded decisions. As we have seen, one such cause is the trickery of certain compliance practitioners, who seek to profit from the mindless and mechanical nature of shortcut responding. If, as it seems, the frequency of shortcut responding is increasing with the pace and form of modern life, we can be sure that the frequency of this trickery is destined to increase as well.

What can we do about the expected intensified attack on our system of shortcuts? More than evasive action, I urge forceful counterassault; however, there is an important qualification. Compliance professionals who play fairly by the rules of shortcut responding are not to be considered the enemy; to the contrary, they are our allies in an efficient and adaptive process of exchange. The proper targets for counter-aggression are only those individuals who falsify, counterfeit, or misrepresent the evidence that naturally cues our shortcut responses.

Let’s take an illustration from what is perhaps our most frequently used shortcut. According to the principle of social proof, we often decide to do what other people like us are doing. It makes all kinds of sense since, most of the time, an action that is popular in a given situation is also functional and appropriate. Thus, an advertiser who, without using deceptive statistics, provides information that a brand of toothpaste is the largest selling has offered us valuable evidence about the quality of the product and the probability that we will like it. Provided that we are in the market for a tube of good toothpaste, we might want to rely on that single piece of information, popularity, to decide to try it. This strategy will likely steer us right, will unlikely steer us far wrong, and will conserve our cognitive energies for dealing with the rest of our increasingly information-laden, decision-overloaded

environment. The advertiser who allows us to use effectively this efficient strategy is hardly our antagonist but rather our cooperating partner.

The story becomes quite different, however, when a compliance practitioner tries to stimulate a shortcut response by giving us a fraudulent signal for it. The enemy is an advertiser who seeks to create an image of popularity for a brand of toothpaste by, say, constructing a series of staged “unrehearsed interview” commercials in which an array of actors posing as ordinary citizens praises the product. Here, where the evidence of popularity is counterfeit, we, the principle of social proof, and our shortcut response to it, are all being exploited. In an earlier chapter, I recommended against the purchase of any product featured in a faked “unrehearsed interview” ad and urged that we send the product manufacturers letters detailing the reason and suggesting that they dismiss their advertising agency. I also recommended extending this aggressive stance to any situation in which a compliance professional abuses the principle of social proof (or any other weapon of influence) in this manner. We should refuse to watch TV programs that use canned laughter. If we see a bartender begin a shift by salting the tip jar with a bill or two, that bartender should get no tip from us. If, after waiting in line outside a nightclub, we discover from the amount of available space that the wait was designed to impress passersby with false evidence of the club’s popularity, we should leave immediately and announce our reason to those still in line. In short, we should be willing to use boycott, threat, confrontation, censure, tirade, nearly anything, to retaliate.

I don’t consider myself pugnacious by nature, but I actively advocate such belligerent actions because in a way I am at war with the exploiters. We all are. It is important to recognize, however, that their motive for profit is not the cause for hostilities; that motive, after all, is something we each share to an extent. The real treachery, and what we cannot tolerate, is any attempt to make their profit in a way that threatens the reliability of our shortcuts. The blitz of modern daily life demands that we have faithful shortcuts, sound rules of thumb in order to handle it all. These are no longer luxuries; they are out-and-out necessities that figure to become increasingly vital as the pulse quickens. That is why we should want to retaliate whenever we see someone betraying one of our rules of thumb for profit. We want that rule to be as effective as possible. To the degree that its fitness for duty is regularly undercut by the tricks of a profiteer, we naturally will use it less and will be less able to cope efficiently with the decisional burdens of our day. That we cannot allow without a fight. The stakes are far too high.

Summary

Modern life is different from any earlier time. Because of remarkable technological advances, information is burgeoning, choices and alternatives are expanding, knowledge is exploding. In this avalanche of change and choice, we have had to adjust. One fundamental adjustment has come in the way we make decisions. Although we all wish to make the most thoughtful, fully considered decision possible in any situation, the changing form and accelerating pace of modern life frequently deprive us of the proper conditions for such a careful analysis of all the relevant pros and cons. More and more, we are forced to resort to another decision-making approach—a shortcut approach in which the decision to comply (or agree or believe or buy) is made on the basis of a single, usually reliable piece of information. The most reliable and, therefore, most popular such single triggers for compliance are those described throughout this book. They are commitments, opportunities for reciprocation, the compliant behavior of similar others, feelings of liking or friendship, authority directives, and scarcity information.

Because of the increasing tendency for cognitive overload in our society, the prevalence of shortcut decision making is likely to increase proportionately. Compliance professionals who infuse their requests with one or another of the triggers of influence are more likely to be successful. The use of these triggers by practitioners is not necessarily exploitative. It only becomes so when the trigger is not a natural feature of the situation but is fabricated by the practitioner. In order to retain the beneficial character of shortcut response, it is important to oppose such fabrication by all appropriate means.

Study Questions

Critical Thinking

- Pick any three of the weapons of influence described in this book. Discuss in each case how the weapon could be used to enhance compliance in what you would consider an exploitative manner and in what you would consider a nonexploitative manner.

- For each of the three weapons of influence you choose, describe the way you would defend yourself should the weapon be used against you in an exploitative fashion.

- Describe the three most important lessons that you have learned about the influence process from this book.

References

Aaker, D. A. (1991).

Managing brand equity.

New York: Free Press.

Abrams, D., Wetherell, M., Cochrane, S., Hogg, M. A., & Turner, J. C. (1990). Knowing what to think by knowing who you are.

British Journal of Social Psychology, 29

, 97–119.

Adams, G. R. (1977). Physical attractiveness research: Toward a developmental social psychology of beauty.

Human Development, 20

, 217–239.

Albarracin, D., & Wyer, R. S. (2001). Elaborative and nonelaborative processing of a behavior-related communication.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27

, 691–705.

Allgeier, A. R., Byrne, D., Brooks, B., & Revnes, D. (1979). The waffle phenomenon: Negative evaluations of those who shift attitudinally.

Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 9

, 170–182.

Allison, S. T., & Messick, D. M. (1988). The feature-positive effect, attitude strength, and degree of perceived concensus.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 14

, 231–241.

Allison, S. T., Mackie, D. M., Muller, M. M., & Worth, L. T. (1993). Sequential correspondence biases and perceptions of change.

Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19

, 151–157.