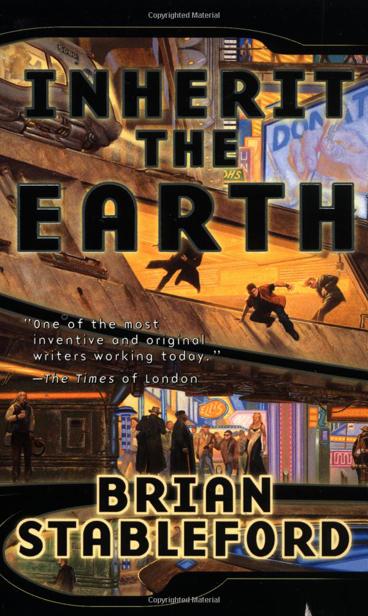

Inherit the Earth

Authors: Brian Stableford

BRIAN STABLEFORD

This is a work of fiction. All the characters and events portrayed in this novel are either fictitious or are used fictitiously.

INHERIT THE EARTH

Copyright © 1998 by Brian Stableford

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or portions thereof, in any form.

A much shorter and substantially different version of this novel entitled “Inherit the Earth” appeared in the July 1995 issue of

Analog

.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Edited by David G. Hartwell

Designed by Nancy Resnick

A Tor Book

Published by Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10010

Tor Books on the World Wide Web:

http://www.tor.com

Tor® is a registered trademark of Tom Doherty Associates, Inc.

ISBN 978-0-312-86493-4

First Edition: September 1998

Printed in the United States of America

0 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jane, and all those who toil in the forge of the will

I am grateful to Stanley Schmidt, the editor of

Analog

, for buying the shorter version of this story, thus establishing its ideative seed and its commercial credentials. I am grateful to David Hartwell for suggesting that I rewrite the final section so drastically as to obliterate any lingering similarity to the ending of the earlier version, thus proving my versatility. I should also like to pay my respects to Eric Thacker and Anthony Earnshaw, who provided their illustrated novel

Wintersol

with a dedication that would otherwise have been ideal for this book: “To the meek, who will only inherit the Earth by forging the Will.”

One

OneS

ilas Arnett stood on the bedroom balcony, a wineglass in his hand, bathing in the ruddy light of the evening sun. He watched the Pacific breakers tumbling lazily over the shingle strand. The ocean was in slow retreat from the ragged line of wrack that marked the height of the tide. The dark strip of dead weed was punctuated by shards of white plastic, red bottle tops and other packaging materials not yet redeemed by the hungry beach cleaners. They would be long gone by morning—one more small achievement in the great and noble cause of depollution.

Glimpsing movement from the corner of his eye, Silas looked up into the deepening blue of the sky.

High above the house a lone wing glider was playing games with the wayward thermals disturbed by the freshening sea breeze. His huge wings were painted in the image of a bird’s, each pinion feather carefully outlined, but the colors were acrylic-bright, brazenly etched in reds and yellows. Now that the gaudier birds of old were being brought back from the temporary mists of extinction mere humans could no longer hope to outdo them in splendor, but no actual bird had ever been as huge as this pretender.

Silas frowned slightly as he watched the glider swoop and soar. The conditions were too capricious to allow safe stunting, but the soaring man was careless of the danger. Again and again

he dived toward the chalky cliff face that loomed above the ledge on which the house was set, only wheeling away at the last possible moment. Silas caught his breath as the glider attempted a loop which no bird had ever been equipped by instinct to perform, then felt a momentary thrill of irritation at the ease with which his admiration had been commanded.

Nowadays, a careless Icarus would almost certainly survive a fluttering fall from such a height, provided that he had the best internal technology that money could buy. Even the pain would quickly be soothed; its brutal flaring would merely serve as a trigger to unleash the resources of his covert superhumanity. Flirtation with catastrophe was mere sport for the children of the revolution.

Silas’s sentimental education had taken place in an earlier era, when the spectrum of everyday risks had been very different. His days with Conrad Helier had made him rich, so he now had all the benefits that the best nanotech repairmen could deliver, but his reflexes could not be retrained to trust them absolutely. The bird man was evidently young as well as rich:

authentically

young. Whatever PicoCon’s multitudinous ads might claim, the difference between the truly young and the allegedly rejuvenated Architects of Destiny was real and profound.

“Why does the sun look bigger when it’s close to the horizon?”

Silas had not heard his guest come up behind him; she was barefoot, and her feet made no sound on the thick carpet. He turned to look at her.

She was wearing nothing but a huge white towel, wrapped twice around her slender frame. The thickness of the towel accentuated her slimness—another product of authentic youth. Nanotech had conquered obesity, but it couldn’t restore the full muscle tone of the subcutaneous tissues; middle age still spread a man’s midriff, if only slightly, and no power on earth could give a man as old as Silas the waist he had possessed a hundred years before.

Catherine Praill was as young as she looked; she had not yet

reached her full maturity, although nothing remained for the processes of nature to do, save to etch the features of her body a little more clearly. The softness of her flesh, its subtle lack of focus, seemed to Arnett to be very beautiful, because it was not an effect of artifice. He was old-fashioned, in every sense of the word, and unrepentant of his tastes. He loved youth, and he loved the last vestiges which still remained to humankind of the natural processes of growth and completion. He had devoted the greater part of his life to the overthrow of nature’s tyranny, but he still felt entitled to his affection for its art.

“I don’t know,” he said, a little belatedly. “It’s an optical illusion. I can’t explain it.”

“You don’t know!” There was nothing mocking in her laughter, nothing contrived in her surprise. He was more than a hundred years older than she was; he was supposed to know everything that was known, to understand everything that could be understood. In her innocence, she expected nothing less of him than infinite wisdom and perfect competence. Men of his age were almost rare enough nowadays to be the stuff of legend.

He bowed his head as if in shame, then took a penitent sip from the wineglass as she looked up into his eyes. She was a full twenty centimeters shorter than he. Either height was becoming unfashionable again or she was exercising a kind of caution rare in the young, born of the awareness that it was far easier to add height than to shed it if and when one decided that it was time for a change.

“I gave up trying to hold all the world’s wisdom in my head a long time ago,” he told her. “When all the answers are at arm’s length, you don’t need to keep them any closer.” It was a lie, and she knew it. She had grown up with the omniscient Net, and she knew that its everpresence made ignorance more dangerous, not less—but she didn’t contradict him. She only smiled.

Silas couldn’t decipher her smile. There was more than amusement in it, but he couldn’t read the remainder. He was glad of that small margin of mystery; in almost every other respect, he could read her far better than she read him. To her, he must be

a paradox wrapped in an enigma—and that was the reason she was here.

Women of Cathy’s age, still on the threshold of the society of the finished, were only a little less numerous than men of his antiquity, but that did not make the two of them equal in their exoticism. Silas knew well enough what to expect of Cathy—he had always had women of her kind around him, even in the worst of the plague years—but men of his age were new in the world, and they would continue to establish new precedents until the last of his generation finally passed away. No one knew how long that might take; PicoCon’s new rejuve technologies were almost entirely cosmetic, but the next generation would surely reach more deeply into a man’s essential being.

“Perhaps I did know the answer, once,” he told her, not knowing or caring whether it might be true. “Fortunately, a man’s memory gets better and better with age, becoming utterly ruthless in discarding the trivia while taking care to preserve only that which is truly precious.” Pompous old fool! he thought, even as the final phrase slid from his tongue—but he knew that Cathy probably wouldn’t mind, and wouldn’t complain even if she did. To her, this encounter must seem untrivial—perhaps even truly precious, but certainly an experience to be savored and remembered. He was the oldest man she had ever known; it was entirely possible that she would never have intimate knowledge of anyone born before him. It was different for Silas, even though such moments as this still felt fresh and hopeful and intriguing. He had done it all a thousand times before, and no matter how light and lively and curious the stream of his consciousness remained while the affair was in progress, it would only be precious while it lasted.