Read Insects Are Just Like You and Me Except Some of Them Have Wings Online

Authors: Kuzhali Manickavel

Insects Are Just Like You and Me Except Some of Them Have Wings (7 page)

Every day at 4 p.m. we drink coffee at the railway station. We burn our fingers and tongues while the Chennai-Mayavaram Express stretches along the tracks like a dead snake.

“That fraud banana woman asked thirty rupees for a bunch today,” says Selva.

“What did you say?”

“I said ‘fuck off’. She sells to everyone else for ten.”

Selva and I are cursed. We have silhouettes that don’t fit anywhere, even though we go to the temple every Friday and have a leaky roof.

“You smell nice,” he says.

“It’s this medicated soap. I got contact dermatitis.”

“You still smell nice.”

•

For some reason our house attracts ravens. They settle on the railing like monsoon clouds and don’t do anything when we wave our arms and say ‘Shoo!’ They have stolen five spoons and thrown one of Selva’s sandals into the gutter. One day they took our guppies. We point to the empty fishbowl when we tell people about it but nobody believes us.

•

Some nights Selva gets entangled in my hair, his eyes darting back and forth as we listen to the moths swarming at our window. They whisper behind their wings about our white tongues, how coarse and dry our hair is. How we keep blaming the ravens for everything.

“Why are we here?” I ask.

Selva covers my eyes with his hands.

“We’re not,” he says.

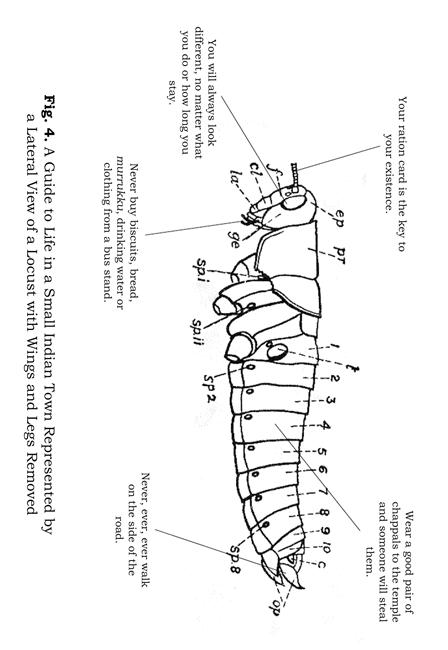

Character 1 keeps his ties and a light bulb on the dashboard of his car. The ties are there because he keeps forgetting to take them inside. The light bulb is there because he can’t remember where it’s supposed to go. He has a feeling it has been there for a long time.

Character 2 likes to collect imaginary diseases and key chains. Her past is littered with dead pets which include fish, squirrels, cats and a fresh-water shrimp called Caesar that was accidentally boiled to death when she put the fish bowl in the sun.

Character 1 buys a black and white fish because it doesn’t look real. He thinks it looks spirited and pixelated and the man in the shop says that’s because of its spots. Character 1 believes it would be perfect for the empty fishbowl in Character 2’s room.

Character 2 comes home and finds that her lucky bamboo has died. It has rotted into a brown mush and attracted a steady line of red ants. She thinks of all the things that she has named, fed, sang to and stapled into her memory.

Character 1 sits outside Character 2’s bedroom door, watching two jumping spiders spar on the wall. He isn’t sure why she was crying but she isn’t anymore. She promises to come out and he promises to bring her a plate of fried noodles. When he gets back in the car he sees the black and white fish staring in mute surprise at the sky.

I almost wore short sleeves today. It was perfect weather for lemon yellow and green apple, but the sun kept lighting up the scars that run along the inside of my forearm like puckered rivers. They are a tattooed testament to my own laws of physics; a body under immense pressure seeks release through the nearest available wrists. Results may vary—in case of failure, avoid short sleeves.

•

Mrs. Krishnan may have worn short sleeves once, possibly at a friend’s birthday when she was in college. She may have powdered her arms but not waxed them. She may have worn a full-length skirt to make up for the inadequacies of her sleeves.

There is a good chance she did not have any scars.

•

Mrs. Krishnan should be sold in little plastic vials at ten rupees a tablet. She is better than Spirulina. She’s like super-charged carrots and spinach without the bother of carrots and spinach. She opens the lungs, revitalizes the brain and stimulates blood flow to the heart. No ingestion necessary. Even if you are wasted and useless at the ripe old age of twenty-four, Mrs. Krishnan will make you feel salvageable.

Your sleeves might even go up inadvertently.

•

Mrs. Krishnan is wearing a blue sari today. She looks like she has draped the sea over her shoulder and I tell her so. A black handbag hangs from her arm like a dead crow but I decide not to tell her that. She doesn’t seem very talkative today.

Mrs. Krishnan has a son in the States and a husband who wants to take her out for dinner tonight, which Mrs. Krishnan thinks is silly—she tells me this as she combs my hair. She says I should know better than to go out in public looking like a scarecrow. She doubts that I even oil my hair. Then she suddenly wonders if I wash my hair at all.

I guess she is talkative today.

•

My hair is in a tiny braid, my hands are neatly folded on my lap and Mrs. Krishnan is very pleased. She does not tell me I look beautiful because Mrs. Krishnan does not lie—she just says it is good. It inspires her to muse on my future prospects. With such a neatly combed head and well-behaved hands I could resume my studies. Or I could find myself a job and start making some money. Or if I wanted, I could find a nice man and settle down. Mrs. Krishnan is sure that I will find someone though she is not sure where. We both agree we will not find him here.

•

Time always tosses me out before I am ready to go. I am sure I just got here and already I am outside, watching an aggressive bank of dark clouds crowd over the setting sun. I know it will be a damp, gloomy day tomorrow, void of any short sleeve conflicts.

The high point will come at 3:45 p.m. when I will meet Mrs. Krishnan. She will hold my hand and tell me about her son in the States and her husband who wants to take her out to dinner that evening, which she thinks is silly. She will comb my hair and tell me to keep my hands still. Then she will say that I can resume my studies, find a job or find a man—I can do whatever I want.

I look at the sky and realize I have no idea what tomorrow will be like. There is every chance of it clearing up into another short sleeves day.

When Aparna Srinivasan’s wedding invitation arrived, Kalai threw it out because she couldn’t really remember who Aparna Srinivasan was. Shivani, on the other hand, pinned it to her soft-board at work, took out a piece of paper and began to map out everything she knew about Aparna Srinivasan’s existence. She used purple for things she knew had happened and red for things she thought would happen. She called Kalai every half hour to report on her progress.

“She ate bread with curd, remember? And garlic pickle. Bread, curd, garlic pickle, I’m surprised she didn’t kill herself. Girls like that

always

kill themselves, it’s like having three nipples.”

“Who has three nipples?”

“I’m just saying.”

“Who are you talking about?”

“Srinivasan, da. College Srinivasan. We should go see her. Don’t you want to see her?”

“I’m not sure. Let me think about it and I’ll get back to you.”

Kalai spent the rest of the afternoon listening to her hands. The heat was making them swell up; she could hear millions of dead seeds and dried tubers jostling against her bones and skin. She fell asleep in her chair and dreamed her hands were huge balloons. They carried her over ships filled with sailors who whistled at her and said

hey girliegirlie

. She tried to whistle back but ended up spitting at them. The sailors started spitting back at her and Kalai wished she had winked at them instead.

•

Kalai decided to join Shivani on her visit because she had nothing better to do. Aparna’s house was simmering under the stress of impending nuptials. The small town relatives were seated in the kitchen cutting vegetables while the American relatives were sleeping with their socks on in an air-conditioned room. Aparna’s room was dark and forgotten, covered with posters of babies emerging from cabbages or peeping out of watering cans. All of the faces had been plastered over with pictures of leafy green vegetables and light bulbs.

“I feel like dying,” sobbed Aparna.

“You’re what?” said Kalai.

For some reason Aparna was whispering and Kalai couldn’t follow a word she was saying.

“Isn’t this the guy you were going out with?” said Shivani.

“So? What difference does that make?” whispered Aparna.

“That’s what I thought,” said Shivani. “That’s what I wrote down.”

“I feel like if I go through with this I will die and nobody will know about it. My body will keep moving but I’ll be dead and nobody will know. Maybe it won’t matter. Maybe that’s the whole point.”

“Why are we whispering,” said Kalai. “Is it because the lights are off?”

“I was thinking of Damayanthi,” whispered Aparna, furiously cracking her knuckles. “We spent the entire study holidays in final year together, the whole month. I don’t understand how you can spend an entire month with someone and then that’s it. Explain to me how that happens.”

“Who’s Damayanthi?” said Kalai.

“That American girl, she kept saying her name was Damn-My-Aunty, remember?” said Shivani. “She was from Idaho. Iowa. Something with ‘I’.”

Aparna opened her mouth in a silent sob; for a second she seemed suspended in time. Then Shivani tapped her on the shoulder.

“You have a pen I could borrow? Or a pencil?”

“What for?” said Aparna.

“I have to write this down.”

“You’re writing this down?”

“Or maybe you have a red colouring pencil? Or crayon?” said Shivani unfolding her chart.

“You’re writing this down?” Aparna said again. She seemed to have said it louder this time and Kalai wondered if something was going to happen. She didn’t feel prepared for anything violent and suddenly wished she hadn’t come.

“How about a red felt pen?” said Aparna. “I have one that smells like cherries.”

“Oh Damn-My-Aunty!” said Kalai, nodding her head. “Big, square girl. Looked like a box. Yes, I remember her now.”

•

On the way home, Kalai looked down at her hands and began to miss them. She suddenly wondered if there were precautionary measures she should take, if there was some kind of compensation available somewhere.

“Aparna used to say ‘bloody babies’, remember?” said Shivani. “She never said ‘bloody hell’ or ‘bloody fuck’. If it was something really mind-blowing she said ‘bloodybastardbitch’. No babies.”

“Bloodybastardbitchbabies.”

“I actually thought she would become a banker. Somewhere in Coimbatore or Trichy maybe. I thought she’d have a room at the YWCA and she would go to church on Sunday. She would convert to Christianity and go to church, that’s what I thought.”

Shivani frowned and waved her forefinger in the air.

“I think I was mostly right, no?” she said. “What do you think?”

“I think that if it doesn’t rain soon my hands are going to explode.”

•

On their next visit, Kalai noticed that Aparna’s house was in exactly the same state as they had left it. The American relatives were still sleeping with their socks on, the local relatives were still cutting vegetables and Aparna was still wearing the same clothes. Her room smelled sour and a laptop was glowing on the bed.

“I had Damayanthi’s email,” said Aparna. “She emailed back. And then I had to chat with her. I’m waiting for her to go to sleep. Isn’t it night over there? Shouldn’t she be sleeping now?”

“I think she just pinged you,” said Shivani. “

Hey-babe-you-there

.”

Aparna slumped down on the floor and yawned.

“I actually saw this coming,” said Shivani. “I wrote it down. In red, see?”

“She sent pictures of this trip she took to Vietnam,” said Aparna. “Why would anyone go to Vietnam?”

“Or Germany,” said Kalai. “I never got why people went to Germany.”

“Take me out,” said Aparna, getting up. “The two of you should take me out.”

“Why?”

“Because I’m getting married. Buy me lunch or something. Take me to a movie. You have to take me someplace.”

They waited in the corridor while Aparna got ready. Kalai sat on the floor and tried to flex her fingers.

“Why do we have to take her someplace? I don’t want to take her someplace,” said Kalai.

“We’ll drive around and then she’ll get bored,” said Shivani, frowning at her chart. “I’m going to need another sheet of paper.”

•

They hoped that Aparna would eventually ask them to take her home but she didn’t. They ended up at Shivani’s place, which was perched like an afterthought on a corner of somebody’s roof. As soon as they arrived, Aparna sat down on the floor and took out a bottle of vodka and a notebook from her bag.

“So Kalai,” said Aparna. “What do you say when people ask why you’re still single?”

“I tell them my genitals fell off,” said Kalai.

“How do you say genitals in Tamil?”

“I don’t actually say genitals. I pat my upper thigh and say

ellaamai veezhinthiduchu

.

1

”

“I hope you both have eaten something,” said Shivani. “You guys can’t be sick here, there’s no water. I only get water in the morning and evening.”

“Do you know this old Tamil song?” said Aparna.

“Kaalam oru naal maarum / Nam kaavalaigal yaavum theerum / Varuvathu yennee sirikindren / Vanthathu yenne azhukindren.

2

”

“No but have you ever noticed how old Tamil songs sometimes sound Chinese?” said Kalai. “I think it’s all those twangy stringed instruments.”

“How come there are no Tamil songs about genitals?” said Aparna. “How come I know the name for genitals in other languages but not in Tamil? Why is life fucked up like that?”

Shivani suddenly appeared holding a plate of fried eggs.

“What are you doing?” said Kalai.

“You don’t eat eggs?”

“Why are you giving us eggs?”

“You have to eat something, I’m not having you two puking all over my house, there’s no water.”

“

Kanavu kaanum vazhkaiyaavum / Kalainthu pohum kolangal,”

sang Aparna.

“Thuduppu kuda baaram endru / Karaiye thaidum odangal

3

.

”

Aparna’s song slowly disintegrated into a mess of sobs. She crumpled into a hiccoughing pile of broken girl, her elbows and knees flapping as if they were unsure of what to do.

“Don’t cry,” said Kalai, even though it seemed like a very useless thing to say.

“I want to know how this happened,” sobbed Aparna. “How did all this happen?”

“Nothing happened,” said Kalai.

“Exactly!”

“Nothing happens to a lot of people.”

“Then what’s the fucking point?”

Kalai became aware of her wrists, dangling beside her like broken tree branches. She couldn’t feel her hands and for a second she wondered if they had fallen off.

“How about a boiled egg?” said Shivani. “Or an omelet?”

•

Aparna sipped her vodka with a straw while Shivani dusted her bookshelf, swept the floor and rearranged her refrigerator. The plate of fried eggs hardened on the table and Kalai felt her hands grow heavier under the strain of the rainless sky and alcohol. She remembered a cartoon character whose hands kept changing into large hams and she thought, so that’s what they mean. This is what they were trying to say. She began to bounce her hands on the ground, watching her fingers flail and curl like fat worms.

“I’m going to ask the landlady for extra buckets, evening water will be coming soon,” said Shivani. “Make sure Aparna doesn’t puke. If she does, make her puke in the garbage can.”

“What if I puke?” asked Kalai.

“What did I just say, puke in the garbage can. I don’t have a special place for your vomit.”

Kalai slumped against the wall, overcome with mournful feelings and nausea. She saw herself laden with possibilities, each one hanging from her chest like a dead baby. Be proactive Kalai, she said to herself. Make a fist. Pray for rain. Wear a sari so the young men can see your waist. Carry your breasts like offerings. Don’t fart in public.

Aparna suddenly lurched up, clutching her notebook.

“Have you ever felt like all you had left was the box?” she said. “Like you used everything else and then there was just the box?”

“What box?” said Kalai.

“Sometimes I think how we’re born with these things—”

“Birth defects.”

“No, we’re born with things and they’re like… ice sculptures. And it’s like if we don’t do something with the ice sculpture it melts and we are left with nothing. There’s just the box. I mean if ice sculptures came in boxes, that’s all that would be left. You know?”

“That’s birth defects, what you’re talking about. Sometimes they go away. I had a mole and I thought it would go away once.”

Aparna stumbled across the room to the balcony, which had enough room for half a person to stand in. She climbed on the cement railing, swaying slightly.

“Kalai I’m so sorry your genitals fell off,” said Aparna. “I don’t know how you’ll find a man now, considering you aren’t very good-looking.”

“What are you going to do?” said Kalai.

“Jump I guess. I can’t think of anything else worth doing, can you?”

“Be proactive.”

“This is proactive. It’s something as opposed to nothing.”

“Oh, then that’s different. Then yes.”

“Then you think I should do it?”

“Absolutely.”

“You think I should jump off this balcony and kill myself.”

“I really do.”

Aparna nodded and climbed down again. She walked towards Kalai with huge, careful steps and then paused, as if she was thinking about something.

“You stupid, scummy fuck,” she said.

“Hmm?”

Aparna suddenly began hammering her notebook into Kalai’s ear.