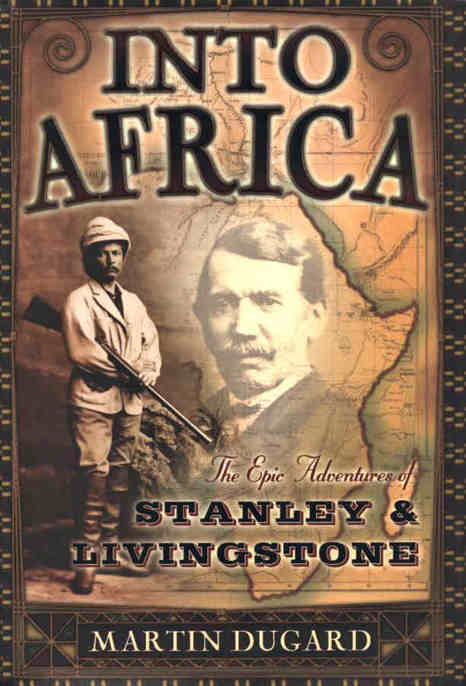

Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley & Livingstone

Read Into Africa: The Epic Adventures of Stanley & Livingstone Online

Authors: Martin Dugard

Tags: #Biography, #History, #Explorers, #Africa

THE DRAMATIC RETELLING OF THE

STANLEY-LIVINGSTONE STORY

MARTIN DUGARD

To Calene with Love

We also rejoice in our sufferings, because we know that suffering produces perseverance; perseverance, character; and character, hope — and hope does not disappoint us.

ROMANS 5:3–5

Map: The Forest Plateau of Africa

II SOMEWHERE IN THE MIDDLE OF NOWHERE

IV THE WORLD TURNED UPSIDE DOWN

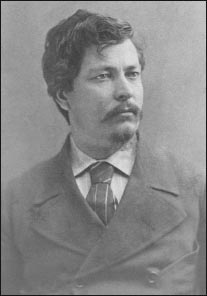

Henry Morton Stanley, 1866

© Bettmann/CORBIS

Dr David Livingstone with his daughter, Anna, before leaving England to search for the Source of the Nile

© CORBIS

15 MARCH 1866

Zanzibar

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS

to the day after first setting foot in Africa, and just four days before his fifty-third birthday, David Livingstone was holed up in a small house on the island of Zanzibar, waiting for a ship to take him back to his beloved continent. He had been away nearly three years and was impatient to return. The mere thought of mingling with African villagers, tramping through pristine wilderness, and ‘the stimulus of remote chances of danger either from beasts or men’ exhilarated him.

Livingstone had been stuck on the small island, just twenty miles off the coast of East Africa, since January. With every day that passed, he grew more disgusted by it. Zanzibar had once been a tropical paradise, lush with palm and mango trees, swept by sensual trade winds. But now the island was choked with people. Piles of human excrement and trash were stacked on the sandy beaches and the air smelled putrid at low tide. In the largest city, also Zanzibar, diplomats and merchants from the United States, Great Britain and the European continent battled for control of East Africa’s expanding regional economy, even as they turned a blind eye to the slave trade

Livingstone had fought so hard to end. Newly captured African men, women and children, still wearing the manacles and dog collars from their long march out of the African interior, were imprisoned in caves beneath the island, waiting for the day they would be sold in the city market.

The mood throughout Zanzibar was menacing, transient, bristling with compromise. Livingstone ached to be away from the chaos, in the wilds of Africa, alone.

Zanzibar, however, was also where European explorers bought their supplies and began their journeys into Africa’s unknown heart. Livingstone was one of those men. Many said he was the best — or had been, in his prime. Now, in his fifties, Livingstone was about to begin the most ambitious expedition of his career. His goal was to achieve the Holy Grail of discovery: to determine once and for all the Source of the Nile River — a challenge that had eluded scores of worthy explorers through the centuries. And while there was a time when his prowess was so esteemed, and his expeditions imbued with such moral purpose, that finding the Source was almost beneath him, now he needed this accomplishment desperately. It would not only seal his legacy — it would restore him to the pinnacle of world exploration.

Before leaving England he’d assured his children and friends the journey would take just two years — an uncharacteristically brief sojourn for Livingstone. He would breach the African continent on its eastern shore, then travel west into the interior with the assurance of a man who had been there before. Livingstone knew the land, knew where he was going and knew where he would likely find the Source. Two years seemed an accurate prediction.

At first glance Livingstone seemed too benign and diminutive — too

religious

— to pursue such an epic undertaking. His spiritual aura was so great that even the Arab slave raiders against whom he battled so vehemently said he possessed the intangible known as

baraka

, uplifting and blessing all who came into contact with him. But

within Livingstone were also limitless reserves of bravery and perseverance. The thin man with the stutter, crooked left arm and brown walrus moustache had walked across the Kalahari Desert, traced the path of the Zambezi River and, in the journey that made him famous, ambled from one side of Africa to the other. Although the London papers reported his death on more than one occasion, Livingstone was never actually lost, just overdue, for the very nature of exploration meant walking through spaces without the benefit of a map. His treks were rambling, circuitous wanders through jungles, swamp and savannah lasting years and years.

Throughout his travels, Livingstone scrawled copious daily notes. His handwriting had presence — big loops in his lower-case l’s, no slant to his cursive, pithy phrasing — and the journal pages were often flecked with blood or stained by drops of sweat falling from his brow. Those simple words, often written by firelight with mosquito netting draped over his head, were published when his wanders were through. His books became bestsellers. The world learned about Africa through Livingstone’s eyes. Unlocking its greatest mystery was a fitting career summation.

Before Livingstone’s discoveries, geographers surmised that a vast desert lay in the middle of Africa. But as Livingstone travelled between 1841 and 1863 further into that blank section of the map, he saw for himself that Africa’s interior was a marvellous mosaic of highlands, light woodlands, tropical rainforest, plateaus, mountain ranges, coastal wetlands, river deltas, deserts and thick forests. Just like Egypt and the rest of Northern Africa, civilizations had thrived in Southern and Central Africa for millennia. An estimated twenty million people inhabited the interior when Livingstone first arrived. The tribes lived in villages, great and small. Their mud and grass huts with a single low doorway would be clustered within a protective fence of thorn bushes or sharpened stakes. Entire families shared a hut, and entire villages worked together to cultivate the surrounding fields and, if

necessary, wage war. They understood metallurgy, and made spears from iron and copper. Artisans wove fine cloths, baskets and other functional

objets d’art

. Beer was brewed from bananas or grain. Fish and game were plentiful. Coffee was indigenous. Communication between villages and kingdoms was accomplished through a relay of swift runners. This ‘bush telegraph’ allowed information to travel quickly over thousands of miles.

The common root language, which Livingstone quickly learned, was Bantu. An amazing six hundred dialects had spun from that tongue as tribes spread out across the continent over thousands of years. Through the insular nature of Africa’s geography, and the fact that people from other continents were terrified of exploring its interior, Africa’s hidden civilizations had flourished.

One of the primary reasons Europeans stayed away so long dated back to the fifth century BC. While attempting an anti-clockwise circumnavigation of Africa, the Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator dropped anchor on the west coast of Africa, near the equator. He and his men went ashore to hunt game and find fresh water. Slogging into a tropical rainforest, the music of drums and bamboo flutes wafted through the jungle from somewhere not too far off. Hanno and his men were scared, but they stayed the course. Then an enormous black man attacked them. The Carthaginians were in awe of his rippling muscles, great white teeth and full body hair. Fearing for their lives, the Carthaginians killed him. To prove to the world that such a man existed, he was skinned then brought back to Carthage. This ‘gorilla’, as Hanno’s translators called him, terrified all who saw it. That display, plus Hanno’s written account of the voyage, later translated into Greek and distributed throughout the known world, established Africa’s reputation as a savage land. It would be twelve hundred years before Equatorial Africa was penetrated again.