Invisible Romans (15 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

These women not only owned land, but actively oversaw the agricultural arrangements and work:

Thais sends greetings to her own Tigrios. I wrote to Apolinarios to come to do the measuring in Petne. Apolinarios will tell you how the deposits and public duties stand; what name they are in, he will tell you himself. If you come, take out six artabas of vegetable-seed and seal them in sacks so that they are ready, and if you can, go up to search out the ass. Sarapodora and Sabinos greet you. Do not sell the young pigs without me. Farewell. (Rowlandson, no. 173)

As landowners, they actually go themselves and collect rents (Rowlandson, no. 172). Others hired male agents, who sometimes defrauded them, ‘despising [the woman’s] lack of business sense’ (Rowlandson, no. 177). And poorer women actually worked for wages in agriculture:

I, Thenetkoueis daughter of Heron, Persian woman, with as guardian my kinsman Leontas son of Hippalos, agree that I have received from Lucius [Bellenus Gemellus, the owner of the olive press] the 16 drachmas of silver as earnest money, and I shall carry in the oil-press from the day you bid me, receiving from you, Lucius, wages at the same rate as the other carries, and I shall do everything as agreed. (Rowlandson, no. 169)

Other documents show women employed as winnowers. So just as other women worked as weavers in establishments, some rural women were hired directly to work in the fields.

Women controlling their lives

A woman’s legal status clearly demarcated a position of disadvantage before the law. She was not a person at law and could not except in rare instances represent herself as a legal entity, being always in the power, under the legal authority, of a male. However, the legal system could be worked. A compliant male relative could represent her interests; she could instruct a legal guardian to make her will; she could represent herself in court if her own person or property were at issue; she could even, if she qualified and knew her rights, obtain full legal personhood by being the mother of, depending on her status, three or four children. Women used these mechanisms in the system to participate fully in property ownership, making contracts and wills, and other activities. In fact, adult women from all classes except the high elite received fully a fifth of the judicial decisions recorded from the early second to the end of the third centuries

AD

. Women also appealed to the law in adversity, sometimes using the ‘poor little me, a weak woman’ ploy to gain sympathy from the male legal world, which actually believed such to be true. The best evidence for all this comes from Egypt, but is also relevant to women’s experiences elsewhere in the empire. Nevertheless, women in all probability did not in general seek solutions to their issues in the legal system. Like other ordinary people, they used an array of other approaches, for the legal system was corrupt, clumsy, and dominated by elite males – all reasons to avoid it if possible. Of course, documents do not show this – the documents themselves are the products of

those women who did engage with the system – but indications can be gleaned that show how women managed.

In marriage the possession of a dowry, as well as male relatives available for support, helped to mitigate the husband’s domination of a marriage. In most instances, what the husband wished came to be; but in extreme situations divorce was always possible as a way out. The dowry, moreover, served to remind the husband of his economic interest in the relationship; even a dowry that was very small by elite standards could make a big difference for an artisan or small businessman. Children were also a protection. The cultural standard of marriage and family, plus the practical and hubristic desire to have heirs, gave a woman some leverage in the relationship, since her active and passive participation were required. In some situations the partnership of man and wife that was the ideal actually existed; in less ideal situations the realistic importance of the wife as mother, household manager, and helpmate in economic activities was not lost on men, and gave women leverage. And in other instances a woman’s contributions to the family went beyond those of the helpful wife: the ownership of land, the inheritance of significant resources, the connections a wife might bring through her family were all chits that sat waiting to be called in if a husband acted too independently in matters the wife deemed important to her and her family’s welfare. And the strong bond of affection and camaraderie which existed in many relationships should not be neglected. Arranged marriages – the norm in the world of ordinary people – were usually far from cold. The assumption that a couple would grow into a relationship was often realized in reality. Cultural expectations, family pressures, and the bond of children all combined to create a situation in which the marriage would work.

When these failed, a woman could resort to pressure of various kinds. As noted, she could bring the weight of relatives to bear; she could remind her husband, perhaps none too subtly, of her economic importance. But she could also resort to charms and spells to control her husband and her situation. Indeed, men often felt that magic was the most dangerous weapon in a wife’s armory, a corollary to their feeling that women in general had recourse to magic to get their way in interpersonal relationships – a tacit and unacknowledged admission of the powerlessness of women to confront them in their own ‘manly’ world.

These magic spells – bought in the local magic shop, written on slips of papyrus, or simply spoken – were indeed a major weapon for women against the perils of their world, whether in personal or physical trials. One could purchase an individualized spell, or have recourse to general resources such as directing Homeric verses toward specific ills. A papyrus records such a use of verses from the

Iliad,

for example, to deal with a woman’s menstrual problems:

… the wrath of Apollo, the lord who strikes from afar [Iliad

1.75]. This charm, spoken to the blood, heals a bloody flow. If the patient gets well and is ungrateful, take a pan of coals, put [?the amulet on it] and set it over the smoke. Add a root, and also write this verse: …

for this reason he who strikes from afar sent griefs and still will send them [Iliad

1.960].

In such need, women also could have recourse to action magic, as opposed to charms. The healing of a woman with a ‘bloody flow’ in Matthew 10:20–22 is an example of such recourse to magic, for the woman who suffered sought out Jesus, a person with access to supernatural power, in order to find a cure for her ill.

In marriage, as previously noted, the asymmetrical power relationship of husband and wife could be righted by the wife’s use of magic – a thing to be feared and, indeed, in this instance prohibited in the marriage contract:

Thais, daughter of Tarouthinos, swears … I will not nor shall I prepare love charms against you, whether in your beverages or in your food … (Rowlandson, no. 255)

In another instance, magic solves a family problem. A woman whose son had been possessed by a demon for two years came to Apollonius; she begged him to rid her son of this curse. Apollonius wrote a letter to the demon threatening severe action if he did not quit the boy, and gave it to the woman; presumably the demon, when served with the letter, left the boy for good (Philostratus,

Life of Apollonius

3.38). And of course women had recourse to that ever popular use of spells, for love, whether to force a male’s attentions:

I will bind you, Nilos alias Agathos Daimon, whom Demetria bore, with great evils … you are going to love me, Capitolina, whom Peperous bore, with a divine passion, and you will be for me in everything a follower, as long as I wish, in order that you may do for me what I want and nothing for anyone else; that you may obey only me, Capitolina; that you might forget your parents, your children, and your friends … I, Capitolina, possess the power, and you, Nilos, will give back the favors, when we meet …I shall insert this pledge [into its box] in order that you might carry out all the things written on this slip of papyrus, for this is why I am summoning you, my divinities, by the violence that constrains you and the compulsion. Bring all things to completion for me and leap in and snatch up the mind of Nilos, to whom belong these magic articles, so that he may love me, Capitolina, and that Nilos, whom Demetria bore, may ever be with me at every hour of every day. (Rowlandson, no. 285)

Or another woman’s affection:

… demon set on fire the heart, the liver, the spirit of Gorgonia, whom Nilogenia bore, with desire and love for Sophia, whom Isara bore. Compel Gorgonia, whom Nilogenia bore, to be thrown, for Sophia, whom Isara bore, into the bath-house, and you become a bath-woman, burn, inflame, set on fire her soul, her heart, her liver, her spirit, with desire for Sophia, whom Isara bore, drive Gorgonia, whom Nilogenia bore, drive her, torture her body night and day, force her to be an outcast from every place and every house, loving Sophia, whom Isara bore, she, given away like a slave-girl, handing herself and all her possessions over to her … (Rowlandson, no. 286)

Religion also provided weapons a woman could use to control her environment. Her exclusion from the male social world and most specifically from leadership in state and community-wide religious rites was partly compensated for by social interaction gained during religious activities. Festivals were a reason for extended families to get together, and so for women to renew ties and mutual support. They were often direct participants in these festivals, not merely bystanders. The thronging procession in honor of the Egyptian goddess Isis described in the

previous chapter gives a taste of the drama and excitement of such participation. And in Heliodorus’ novel

An Ethiopian Story

(5.15), we find that during a festival in honor of Hermes, with public sacrifice and a banquet, the women eat together in the temple and then dance a hymn of thanksgiving to Demeter, while the men eat in the temple forecourt and afterward sing and pour libations. Festivals were so common in the Romano-Grecian world that it is easy to forget the many opportunities they gave for women to gather, to celebrate, and to interact.

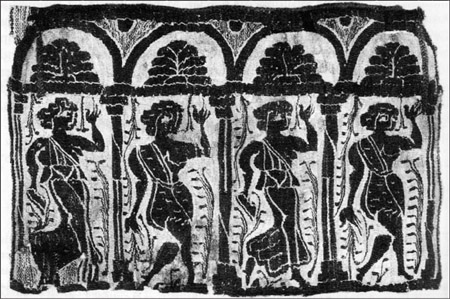

7. Female entertainers. Female as well as male dancers are shown on this textile from late antique Egypt.

But beyond peripheral participation in the cults, what is thought of as ‘official’ religion was largely closed to ordinary women. It was otherwise with regard to cults that could solve a woman’s problems. The multiplicity of sanctuaries and votive offerings related to pregnancy and childbirth indicates the active role of women in these rites; healing divinities also got much attention. And although it is hard to say how prominent women were in the nonstate, noncommunity-oriented cults such as Isis and Christianity – expectation, and the reality, would be that men led these, as in other nondomestic religion – the impression is that these appealed because they were more open to participation by women,

rather than leaving them to be bystanders. This very openness provided women with more support in their daily concerns. The prominent role of Isis as a strong, protective, family-centered Mother, the woman who featured in the Gospel narratives, and appeals to family ideals so prominent in early Christian literature, for example, resonated as women sought ways to deal with issues in their lives. In sum, although women were not leaders in cultic activity beyond the household, they found a steady source of mutual aid in the social networking that festivals and worship allowed, and solutions for their daily problems in specific cultic rituals and activities.

When challenged on their own turf, women could take the offensive to protect their own interests. Far from the Mediterranean, but in a story that surely reflects the aggressiveness of women there, Philostratus has Apollonius tell of an Ethiopian village ravaged by a satyr:

… when suddenly they heard loud shouts from the village as the women there screamed and called to each other to take up the chase and capture the thing

(Life of Apollonius

6.27)

Although this is fiction – unless we want to believe in satyrs – women in real life could act with the same aggressiveness when their interests were at stake. Earlier in this chapter I quoted the evidence from Philo that women in Alexandria were violent participants in riots. In that graphic passage, women were in the street, cursing their foes and assaulting them, too. Women were also present in the theaters, shouting along with their male kin, when those venues were used, as so often, to harangue and punish disturbers of the peace and worse. Their voices were heard.

Conclusion

I have provided much evidence for the active role of ordinary women in their own lives, in the lives of their families, and in life beyond the household, including business contracts, landowning and management, and public socioreligious activities. Within their culture they were not child-producing drones, or mere ornaments. Their activities were woven vividly into every inch of the cultural cloth. This is exactly as

should be expected. The elite could and did as much as possible to keep its women as accouterments rather than as partners. But in the world of ordinaries the ‘luxury’ of closeted, protected women did not exist. All hands were needed to keep the household running smoothly (under good circumstances) and to earn enough to keep the wolf from the door (in more straitened ones). The outspokenness of women, the leverage they had in various ways in their lives with husbands, their economic contributions, their role in the socialization of the next generation: while all these things had to exist within the culture of male domination, the latitude for action and influence was great. It is too much to speak of ‘liberation’; Romano-Grecian culture was unliberated by any modern standard. But as in other preindustrial societies, ordinary women pulled a lot of weight, had a lot of influence, and were strong partners with their husbands or other males in making life choices.