Invisible Romans (38 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

I leave the mythical temple prostitutes and the very real elite courtesans aside, to take up ordinary prostitutes. Roman law defined such a person as ‘any woman who openly makes money selling her body’ (

Digest

23.2.43, pr. 1). The law did not punish prostitution. It was legal and a prostitute could not be prosecuted for her profession. Sexual relations with a prostitute did not constitute adultery, nor could an

unmarried whore be a party to adultery, much less be guilty of adultery herself.

Stuprum

(illegal intercourse) was the term for sexual relations with an unmarried girl/woman (or widow), or boy/man, but it was inapplicable to sexual relations with whores. The key here is inheritance and family inviolability. Sex with a prostitute (at least, a female prostitute) would not endanger the bloodline of the family, nor compromise the sexual purity of a potential wife. Some legal disabilities did, however, adhere. Prostitutes were

probrosae,

meaning, according to Augustan marriage laws, that they could not marry freeborn Roman citizens. They also suffered from

infamia

per the Praetor’s Edict – they could not write a will or receive full inheritance. But these restrictions were probably often flouted or ignored and, at any rate, the stigma disappeared if a prostitute married. The Roman legal system basically left prostitutes alone.

So as far as is known, authorities did not care about the moral aspect of prostitution – after all, intercourse with a whore did not break any laws, or even any moral strictures as far as the man was concerned, since it did not constitute adultery. For the woman there was some disgrace arising from sexual license but, again, there was no legal prohibition or penalty. It is unlikely that prostitutes at first had to register with the authorities; since the elite cared not a whit about ‘controlling’ prostitutes, there would be no reason to go to the trouble to register them. But it did eventually dawn on them that the service was potentially taxable. And by the mid first century ad prostitutes did, indeed, pay a tax. As such a tax was previously known with certainty only at Athens, it is likely that the inspiration for the Roman tax originated from that experience. The first documentary attestation is under the emperor Nero, but the emperor Caligula instituted it

… on the proceeds of the prostitutes at a rate equivalent to the cost of one trick; and it was added to this section of the law, that those who had practiced prostitution or pimping in the past owed the tax to the treasury, and even married persons were not exempt. (Suetonius,

Life of Gaius

40)

Thus the tax, as Suetonius notes, amounted to the value of one trick, and could not be evaded by claiming to have quit the business. In order

to collect this ‘service tax,’ officials would have had to keep some track of who was a whore. The tax (and so responsibility for oversight) was collected in various ways in various parts of the empire, sometimes by tax collectors, sometimes by public officials, most often, it seems, by soldiers detailed for the task. These were supposed to exact the tax, but often engaged in extortion, as well; I think of John the Baptizer urging soldiers to collect no more than their due and to be satisfied with their pay – clearly something that usually did not happen. Prostitutes working independently perhaps presented something of a challenge to tax men; on the other hand, those in private brothels could be registered and tracked, and the municipal brothels would have made it even easier, but that did not stop imperial officials from extorting still more money, as is attested by a document from Chersonesus on the Black Sea coast. The abuses this system worked on the prostitutes themselves can only be imagined.

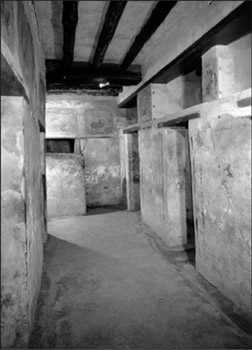

27. A brothel. The only archaeologically identified brothel in the Romano-Grecian world is at Pompeii. Here the prostitutes had the use of small chambers; erotic scenes decorated the wall above each opening.

There was one further way that prostitutes came into contact with the authorities. When there was a festival or other day, perhaps a special market, which brought more people than usual to a town, a one-day permit to prostitutes was issued, presumably with a fee attached, although this is not explicitly attested to. From Upper Egypt comes one such permit:

Pelaias and Sokraton, tax collectors, to the prostitute Thinabdella, greetings. We give you permission to have sex with whomever you might wish in this place on the day given below. Year 19, the 3rd day of the month Phaophi. [signed] Sokraton, Simon’s son. (

WO

1157/Nelson)

Despite lacking the details of just how such a mobile product as sex could be kept tabs on, clearly the Romans managed it. The rate, as we are told by Suetonius, was based on the value of a single trick. A document from Palmyra, far to the eastern end of the empire, actually gives three amounts: a per-trick rate of one denarius or more paid one denarius, a per-trick rate of eight asses (eight-tenths of a denarius) paid that rate, and a per-trick rate of six asses (six-tenths of that coin) paid that rate. Just how much was collected cannot be established, however. The relevant details are unknown, such as how often the tax was collected (daily? Monthly?). So, for example, if a whore charged one denarius, turned five tricks a day, and paid the tax daily, then she would pay 20 percent of her ‘take’ in taxes. But if the tax were assessed monthly and she worked steadily at the same rate, then over, say, twenty days’ work in the month she would earn 20 × 5 = 100 denarii, of which only one would be paid in tax for a 1 percent rate; the lower is much more probable, however, since taxation rates in other environments were usually in the 1–5 percent range. The pimp or even the owner of several brothels might be the person who actually paid the tax, rather than the whore herself. Streetwalkers were probably harassed unmercifully by officials seeking bribes or payment in kind, as were, we can imagine, women who might easily multitask in prostitution and some other technically tax-exempt profession – chambermaids, tavern workers, entertainers. The evidence gives us examples of the tax from far-flung areas of the empire; clearly this tax was widely collected. From Egypt there are even a few receipts, for example:

Pasemis, to Senpsenmonthes, daughter of Pasemis, greetings. I have received from you for the tax on prostitutes at Memnonia for the first year of Nero, the Emperor, four drachmas. Dated the fifthteenth day of the month of Pharmouthi.’ (O.

Berl

Inv. 25474/Nelson)

A tax register, regular collection, a system for granting daily permits – this tax of prostitutes was collected assiduously and, it is reasonable to suppose, brought in quite a good income to the government.

This was, however, the only way the state intervened in prostitutes’ lives unless there was wild disorder or actual injury done in the course of business. And, of course, prostitution could cause or accompany row-diness. As such, the magistrate responsible for local public order – the

aediles

in Rome, for example – kept some watch on their activities. But since it was not illegal to ply their trade, only disruption of public order could bring down any action by officials.

Indeed, such was the lack of concern for the trade that there was no attempt to ‘zone’ for prostitution – no ‘red-light’ district. Venues for prostitution were scattered helter-skelter throughout a city or town. Naturally there would be more activity in some areas than in others – around the forum and temples for example, or, in Rome, in the infamous Subura section – but a whore could be found just about anywhere in a town. As to health considerations, there was absolutely no concern on the part of officialdom. Nor was there much of any practical repercussion to being a prostitute beyond taxation and the social stigma some might attach to the profession.

In the abstract, prostitution must have been very appealing to a person of marketable age and/or desperate condition. The income was potentially good, girls deemed likely prospects were lured with promises of clothing and other enticements, and they had no other skill or product that could bring nearly so much cash – certainly neither weaving nor wet-nursing, the other two primary cash occupations of women. But although some prostitutes operated independently, as is known because they paid the prostitution tax, the system was not geared to favor individual entrepreneurial prostitution. The pimp, a standard character in plays and stories featuring whores, was omnipresent. He (or she; certainly there were female pimps) organized, controlled (when he did not actually own), and exploited the prostitutes. He personally

or as an agent for a wealthy investor collected a large portion of the income from a girl, certainly a third, very possibly more. If quarters or clothing or food were provided, this was all paid for at a premium from earnings. The woman was powerless to resist (literally in the case of a slave, de facto if a free person). Despite the prospect of income, it is easy to believe that a typical prostitute ended up with relatively little take-home pay and, of course, the whole low-life, earn-and-spend atmosphere of brothels and public houses and street-corner solicitation did not encourage foresightful savings plans. But we should not sell the prostitutes short. In the longer run, it seems that many prostitutes were freedwomen, so they must have not only earned enough to buy their freedom from slavery, but continued in the trade after gaining their freedom; a few might become madams and continue their profession indirectly. One Vibia Calybe began as a slave in prostitution and rose to manage her mistress’s brothel as a freedwoman:

Vibia Chresta, freedwoman of Lucius, set up this monument to herself and her own, and to Gaius Rustius Thalassus, freedman of Gaius, her son, and to Vibia Calybe, her freedwoman and brothel manager. Chresta built the memorial entirely from her profits without defrauding anyone. This grave is not to be used by the heirs! (

CIL

9.2029 =

ILS

8287, Benevento, Italy)

And in a risqué poem in honor of the phallic god Priapus, another slave prostitute’s success is recognized:

Telethusa, famous among the whores of the Subura district

Has gained her freedom, I think, from her profits.

She wraps a golden crown around your erection, holy Priapus,

For women like her hold that to be the image of the greatest god.

(

Priapeia

40)

It is telling that Artemidorus notes that seeing a prostitute in a dream portends success:

Thus in dream symbolism the prostitutes have nothing at all in common with the brothel itself. For the former portend positive things; the latter the opposite. To see in a dream street whores plying their trade profits a man. The same goes for prostitutes waiting for business in a brothel, selling something and receiving goods and being on view and having sex. (

Dreams

1.78, 4.9)

On the other hand, many must have died poor, miserable, and forgotten, a fate not unusual for many other ordinary people once their ability to earn even a small income disappeared through age or circumstances. Artemidorus has another interpretation which hints at this:

A woman eating her own flesh means she will become a whore, and thus be fed from her own body. (

Dreams

3.23)

A slave skeleton was found at Bulla Regia in North Africa with a lead collar around her neck intended to make whoever came upon her outside of the town capture her and return her. It read: ‘This is a cheating whore! Seize her because she escaped from Bulla Regia!’ (

AE

1996.1732, Hammam Derradji, Tunisia). It is impossible to imagine that her life was anything but horrible.

There was no shortage of prostitutes. Some were forced into prostitution, perhaps by a family on the edge of starvation, something that is illustrated by a document from Egypt. It tells of how a certain Diodemos, a town councilor of Alexandria, takes a liking to a prostitute and spends many evenings with her, but then murders her. He is arrested and eventually confesses.

And the mother of the prostitute, a certain Theodora, a poor old woman, asked that Diodemos should be compelled to provide for her a subsistence allowance as a small recompense [presumably, for the loss of her daughter’s life]. For she said, ‘It was for this reason that I gave my daughter to the brothel-keeper, so that I should be able to have sustenance. Since I have been deprived of my means of livelihood by the death of my daughter, I therefore ask that I be given the modest needs of a woman for my subsistence.’ The prefect said [to Diodemos], ‘You have murdered a woman who makes a shameful reproach of her fortune among men, in that she led an immoral life but in the end plied her trade … Indeed, I have taken pity upon the wretch because when she was alive she was available to anyone who wanted her, just like a corpse. For the poverty of the mother’s fortune so overwhelmingly oppressed her that she sold her daughter for a shameful price so that she incurred the notoriety of a prostitute.’ (

BGU

4.1024, col. VI/Rowlandson, no. 208)