Isis (7 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

She was with him.

Edyth.

I listened to their love-talk from the hall. When the lights had gone out in his room, I went to the window where Harvey had held on to me to protect me from death’s own embrace.

I peeled back the boards until my fingernails bled.

A shock of cool air burst through from the other side, and I looked out over the sunken garden and across the cliffs to the blackness that was both sea and sky.

I sang softly to the night, “Jack, swing up, and Jack swing down, up to the window, over the ground. Swing over the field and the garden wall—Watch out for Jack Hackaway if you should fall.”

My rages began then, and I could not contain them.

I found myself in the garden that night, beating my fists against the stone wall until it seemed the rock itself bled. In the cellars the next night, where no one could find me. I stood at the door of the Thunderbox Room and thought of Harvey there, washing up after working in the gardens all day, and out along the cliffs, looking at the locked doors of the Tombs and imagining the bones there, the death, the waste and end of all life.

The world is backwards

, I thought.

, I thought.

The living should be dead.

The dead should be living.

The good should be victorious.

The evil should die and stay dead.

I went to the North Wing to hear my grandfather’s enfeebled shouts and curses. I nodded my head as he cried out about wrath and redemption and resurrection and smiting the wicked and praising the good.

I understood, then, where his madness had come from: He, too, had experienced the loss of the good and the victory of the evil.

Sifting through my grandfather’s nude photographs in the study, I began to see the women in them as of the devil himself. I went to my grandfather’s great mahogany desk and searched for the scissors beneath various old papers.

I neatly cut the heads off the women in the pictures. I imagined each was a state execution, and this would kill the women who had somehow influenced Spence to lie with Edyth. I thought of the two of them passing the filthy pictures back and forth as Spence became aroused with passion and Edyth began to allow him intimacies. I took the scissors and the headless photos into the cellars that day, down into the water closet used by servants that led out into the outdoor stairwell. I decided I would flush the pictures down the drain, out of the house, for—having looked at them—I began to even blame the pictures for that terrible day.

In the Thunderbox Room in the cellars, I looked at the cracked mirror, imagining the demons from my grandfather’s books circling around Edyth, tearing at her clothes. I imagined Jezebel and Delilah and Rahab and Ruth and Naomi, headless, coming toward her with a great pair of scissors and cutting off Edyth’s head. I imagined Spence hanging himself from the chandelier in the foyer. All of them dying horribly—even my beloved mother, who had allowed her mind to turn inward and keep her sick so that she would not have to be our mother again; my father, in Burma, or in India, or in one of the war-torn countries that was the source of our wealth; and the Gray Minister, at his own locked window, calling down the Wrath of God upon his household.

My rage burned, and my face felt hot. I leaned over the pump and pushed down on the lever until the ice-cold water poured out into the square sink. I took up a small and worn bar of soap and pressed it to my face. The scent assaulted me. The girls in the kitchen had made this for Harvey. It was my brother’s smell. I splashed my face, scrubbing it with soap and then rinsing it off, closing my eyes as the soap stung beneath my eyelids. When I had washed it all off again, I looked at myself in the mirror, but did not see myself.

I saw Edyth’s face, and it made me furious to see her.

It was as if she had triumphed in some way with Harvey’s death.

It was if his dying had made her permanently part of our family.

As if her words to me when I’d been younger had taken on a reality.

“Someday,” she had said, “you might be where I am and I might be where you are.”

I wanted her to leave. I wanted her to die. I wanted to expose what she and Spence continued to do in this house. I wanted to destroy them both.

Those nude photographs in my grandfather’s Bible were dark and evil, not the beauties of art that I had once imagined them.

No, they were as much demon as the books on summoning demons and ancient spells that my grandfather had collected.

I knew now they were seducers taking from men, from others—to win a battle, to defeat the men that gazed upon them.

They were bad women who sent good men to their deaths.

I took the scissors and looked at my face in the mirror. Looked at Edyth in my mind. At Spence. At my mother.

I hated all of us. Harvey had been too good for the world.

I lifted the scissors and scraped them into the skin of my wrist and carved my brother’s secret name into my own flesh.

OSIRIS

.

.

That is when I first heard a slight noise, as if something were scratching at the window. I almost dreaded glancing over, for I was afraid in some childish and irrational way that I had called some demon to my side. The window into the stairwell showed nothing, yet my sense of dread remained.

When I went out through the door, and then through a second doorway into the mossy stone stairwell with its drains that led up to the grounds from the cellars, it was empty.

I returned to the toilet, and the sound began again, as if something had been waiting for me to return.

Now it was more like some small animal—a mouse, perhaps—batting at its confinement. I glanced about the floor, and looked behind the pipes, but saw nothing. The noise continued, and within it I heard the tiniest of chirps, again like a mouse or a small bird; and the thought went through my head that there was a bird trapped in the toilet bowl.

Somehow, I reasoned, briefly, that a bird had flown in, unnoticed, and had gone into the bowl and was drowning. The irrational notion almost made me smile.

I leaned over the crude chamber-pot of a toilet and drew aside the lid. It was full of reddish-brown water. I supposed no one used the water closet that much here. I drew the lid back over the bowl. At the same time, I noticed that the noise had stopped. I laughed. I reasoned too quickly that it had been the pipes themselves making a strange noise, and perhaps just the act of lifting the toilet lid had been enough to end it.

But the effect of this was as if I had opened an unseen door, or unlatched another hidden shelf in my grandfather’s library. I felt a strange coldness clutch at my throat, and the hairs at the back of my neck stood up as goose bumps covered my arms.

The strange scratching and chirping sound began again.

This time, I was sure it came from the bowl beneath the lid.

I stared at the bowl as the sound became louder, as if—yes—a bird fluttered its wings as it drowned in that dirty water.

I drew the lid aside.

In the water, a swallow—the kind I often saw at twilight swooping and flying along the trees and the eaves of our home—batted at the water as if trying to fly upward.

I felt, for the first time, as if I stood at the edge of some borderland, ill-defined by the physical world.

I thought that, like my grandfather, I might be going mad.

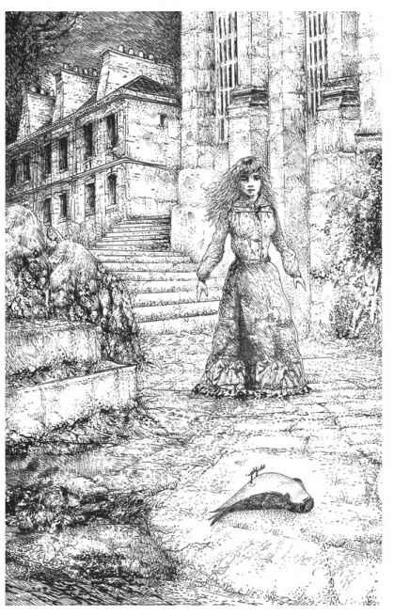

The bird drowned as soon as I reached for it. When I took it out into the night to lay its body down upon the flagstones, I was convinced that I had begun losing my grasp of what was real and what was not.

But I felt that brief spark of what I would later come to regard as psychic ability. That window—which opened in my mind when I fell with my brother—seemed to burst wide again.

That night, I stayed up until dawn, poring over my grandfather’s books of the sacred and the profane.

At sunrise, I went to Spence’s room.

I opened the door to look in on the two of them lying in bed.

I could not even look directly at Edyth or my brother, but instead looked through them.

Edyth shrieked when she saw the scissors in my hands, and while I tried to explain that it was not to hurt her or him, Spence leapt from his bed and knocked them from my fingers.

The scissors scuttled across the floor toward the wardrobe.

“You have to let this go!” he shouted. “You are driving all of us mad! You had no right to come into my room! You have no right to interfere with Edyth! It was you who killed him, Iris! You with your foolishness! I was there when you fell! I stood behind Harvey when he reached for you. You pulled him out of that window, Iris! We could have saved both of you, but you

pulled him out

!”

pulled him out

!”

“It’s a lie! It’s a lie!” I cried, covering my face, trying to block out his terrible voice.

“Ask anyone who was there!” he shouted, his face above me, a monstrous face, a liar’s face. “Ask Edyth! No, ask Percy! Ask Elizabeth from the kitchen! They all saw it. They all saw you reach up and pull him down! If you had just let him draw you up, you both would be here. You are the one who took him to his death! I could kill you, Iris!

I could kill you

!”

I could kill you

!”

I ran out to the Tombs with keys in hand, stumbling several times. My own tears blinded me. I did not understand why my brother had told me such terrible lies, but I knew he was wrong.

I did not pull Harvey out the window. I could not have done it. We were doing our old trapeze act, and I was meant to reach for him. Yet, in my mind, as I recalled those brief moments before we fell, I could not help but now see that Spence was correct. I had been too eager and had felt Harvey lose his balance as I reached up for his arms. But I did not pull him out of the window. He had fallen; it was an accident. If anyone was to blame, it was Edyth Blight. Edyth Blight and her harlotry, and slapping me hard enough that I fell backward from the tall window.

Edyth had killed him and had nearly killed me.

I pressed my hands to my face as I fell down in the grass in front of the doors of the Tombs.

Please, Harvey, let me know you forgive me. Please.

Please, Harvey, let me know you forgive me. Please.

I unlocked the doors of the Tombs and ducked my head to take the steps down among the narrow rock corridors where the Villiers were buried.

I checked the graves marked along the plastered stone wall and looked in the recesses of rock where stone biers had been placed.

I found Harvey’s tomb, and tore a strip of cloth from my dress. I used it as a blindfold, for I wanted to block out all of the world around me. I used it the way Old Marsh had told me blindman’s buff had once been played, not as a game, but as a way of speaking with the dead. I turned about until I was disoriented. Strangely, I did feel as if I had stepped into another world, and in that self-imposed darkness, I began to feel as if others were there, surrounding me.

Other books

Quantico by Greg Bear

Paw Prints in the Moonlight by Denis O'Connor

More Than Neighbors by Janice Kay Johnson

Three Day Summer by Sarvenaz Tash

Parisian Affair by Gould, Judith

Goddess of Yesterday by Caroline B. Cooney

The Dragon and the Lotus (Chimera #1) by Lewis, Joseph Robert

Zombie Queen of Newbury High by Amanda Ashby

All Through the Night by Davis Bunn