Jack the Bodiless (Galactic Milieu Trilogy) (42 page)

Read Jack the Bodiless (Galactic Milieu Trilogy) Online

Authors: Julian May

The fetus said: That is very mysterious. Contrary to common sense!… Why do I find the concept pleasing?

Teresa only laughed. “Do you like the Christmas tree?” She had just installed the star and now moved back a pace or two to study the effect. The little spruce stood on the table in front of the window. It was trimmed with origami cranes made of foil, tiny oatmeal cookies, and gnomes made from pine cones and wire; sculpted hard-baked dough colored with cosmetics formed their tiny heads, hands, and feet.

Jack was tactful: You’ve worked so hard on the Christmas tree. Uncle Rogi is sure to like it. It will be interesting to see all the little fat-cylinders burning at once. Hazardous—but interesting.

Teresa spread a silk scarf in front of the tree as a festive tablecloth, then set out plates, cups, forks, and spoons. “We’ll light the candles when we have dinner. The tree is not going to burn up! Rogi and I will watch it carefully. And after we eat, we’ll give each other these gifts. The things wrapped in cloth lying under the tree.”

Mama, why do you give gifts at Christmas?

“It’s a tradition. Wise men [image] gave gifts to the infant Jesus. To Baby God. And he is God’s gift to us.” She checked the tenderloin roast, which was “resting” in preparation for being carved, and then used the whetstone vigorously on the big knife.

Jack said: That’s the biggest paradox. Even greater than Creation. It was quite unnecessary for God to become human and teach us his love in person. I can see why some Earth religions deny that it happened.

“You’ve been rummaging in my mind again … Yes, Incarnation is quite absurd. But you must admit it would be an excellent way to catch our attention! And so madly elegant. It’s also much easier for us to pray to and love a God-made-man, who would be more likely to understand our human difficulties, than to try to love an almighty Big-Bang-Creator. Why should

he

care if my roast is overdone or if I live long enough for you to be safely born?”

The fetus said: I would like him to care.

“Ah!” Teresa went waddling across the room to grope under Rogi’s bed, where he had hidden the last of the rum.

“Now we’re moving into psychology! An incarnate, loving God takes on significant mythic overtones that appeal to the deepest levels of the human psyche. To that almost instinctive part of us called the collective unconscious.”

I have not yet had any experience of that.

“You will,” Teresa laughed, “when you really begin to socialize.”

I—I wish I did not have to. Even letting Uncle Rogi know me was very frightening at first. There are dark parts to his mind. And I saw darkness in Grandpère Denis’s mind as well, before I shut him out.

“You mustn’t fret about it. All people have good and bad in them. I do, and so do you. This is one reason why a loving God is such an amazing consolation. He has no dark about him at all. God must know all there is to know about us—and yet he loves us anyway. He only wishes us well, even when we’re wicked or when we deny him. We would never have guessed

that

about him in a million years, if he hadn’t told us. It’s mysterious beyond belief … Now let me see: The soup and the rice are keeping warm in covered pots behind the oven, and I have plenty of boiling water for the drinks, and the dessert is—”

Did God become incarnate for the other Milieu races?

“All of them except the Lylmik seem to think that he did. And Milieu anthropologists—or whatever they call themselves—tell us that many of the more primitive races in the Galaxy have Incarnation myths very much like ours. Of course, none of this is

proof

of God’s Incarnation. It can’t be proved. But I believe it, and so does Uncle Rogi, and your Papa and brothers and sisters, and billions of other entities. That kind of belief is called faith.”

She pressed both hands against her enormously swollen abdomen, closed her eyes for a moment, and summoned the image of her unborn child. “I have faith in God’s love just as I have faith in your great future, Jack. There are many things that frighten me and other things that make me very unhappy. But if I can just hold on to faith, I won’t give in to despair. I

won’t.”

Mama—

But at that moment a booted foot began to kick loudly against the door, and Teresa hurried to open it for Rogi. He lurched in, weighted down by a great quantity of wood and enveloped in flying snow and Arctic air.

“Woof! This ought to keep us warm for an hour or two!” He dropped the frozen load, which overflowed the woodbox, and began to shuck off his outer garments. “Something smells mighty good in here.”

“Roast moose tenderloin larded with garlic-salted moose fat. Moose consommé with moose-marrow dumplings and carrots. Rice with moose-and-mushroom gravy. And rum raisin tarts made with moose-fat shortening.” She busied herself at the stove, pouring hot water into two cups, then added other ingredients while Rogi sat on the stool close to the stove, removed his boots, and wiggled his stockinged toes to restore their circulation.

Teresa held out a steaming drink, which Rogi took and sniffed at with incredulous delight. “Hot buttered rum? But I thought all the margarine was long gone.”

“One thinks ahead,” said Teresa solemnly. She lifted her own cup. “A la bonne vôtre, mon cher ami. And merry Christmas.”

“Joyeux Noël to you,” Rogi said, “and to Ti-Jean.”

They touched cups, drank, and kissed each other lightly. Then she made him sit down at the table and begin carving the roast, while she brought the rest of their meal and lit the candles on the tree.

“Don’t worry. I have a bucket of water and a wet cloth handy. We won’t risk a conflagration.” She slipped into her place. She had turned off the two powered lamps, and the two of them sat for a moment side by side with private thoughts, looking at the tiny dancing flames and their reflections in the frost-encrusted window and drinking the aromatic rum.

“It won’t hurt him, will it?” Rogi asked after a while. “The liquor?”

Teresa shook her head, smiling. “It’s well watered, and he’s old enough to handle a little bit … aren’t you, baby?”

The fetus said: It alters my consciousness. Curious! I’ll study the matter.

Both Rogi and Teresa laughed. And then they asked a blessing and began to eat.

Teresa unwrapped Rogi’s gifts to her.

“I have another one, too,” he said, “but it’s out on the porch because it’s not quite finished, so I only put a picture of it in this package along with the other things.”

Teresa stared at a thin slab of wood with a drawing on it, and four peculiar little objects. The artwork showed a simple inverted double-V frame with a thing like a small pack hanging from it. The wooden items looked rather like miniature dumbbells, six or seven centimeters long, with shafts nearly as narrow as toothpicks. Rogi demonstrated how one of the rounded ends was integral with the shaft, while the other could be pulled off with a tug, revealing that the shaft’s end was sharply pointed.

“Those,” said Rogi proudly, “are primitive safety pins. We forgot to bring any. These are made of hardwood, and they took me forever to whittle. Now you won’t have to tie knots in Ti-Jean’s diapers.”

“How marvelous! And the picture—is it a baby swing?”

“Sort of. The woolen duffel-cloth pouch will have an internal padded frame when I get it finished. It’s a papoose carrier. You either hang him up and set him swinging—he can watch you that way—or detach the carrier and put it on your back. It has straps.”

Teresa embraced Rogi and kissed him. “What wonderful presents!” She got up from her chair. “Let me give you a refill of the hot buttered rum, while I get

your

present ready.”

She handed him his drink. The candles on the tree had long since guttered out and the ordinary lamps were glowing on the table amid the remnants of their meal. Teresa directed Rogi to reverse his chair, so that he faced the beds. She turned the two lamps down to their minimal setting and put them on the floor in front of him.

“These are footlights!” she proclaimed. She hung long lengths of flannelette from the overbed shelves down to the floor, nearly hiding the beds. “This is the backdrop! And the stereo is ready with a very specially edited fleck. All that is needed is for the performer to don her costume in her sumptuous dressing room—namely the bath alcove—and then the entertainment will begin.”

She handed him a cloth-wrapped object before she disappeared into the tiny curtained cubicle next to the front door. “This is going to take me a few minutes,” she called. “Better put some wood on the fire! It wouldn’t hurt if you cleared the table, either. But first open the introductory part of your present.”

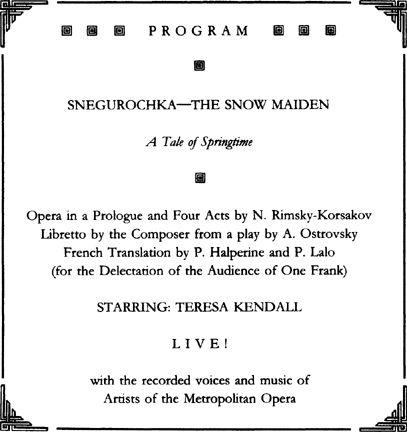

Mystified, he unwrapped another flat piece of wood,

which had an ornamental border drawn around it, featuring vaguely Slavic motifs, and in the center a carefully lettered announcement:

“Well, I’ll be damned,” said Rogi.

He had seen the opera once, on the night of Teresa and Paul’s wedding, but he later admitted to her that he was completely distracted and remembered almost nothing of it. What could Teresa be planning to do now?

He cleared the table and replenished the fire. Then the musical overture began, and Rogi settled back in his chair. Outside, the winter wind hummed and hooted among the eaves. His stomach was full, the little cabin was warm, and the aroma of the hot rum went to his head, befuddling his senses in the most pleasant manner imaginable. The orchestration pouring from the small speakers was lush, romantic,

full of flutes and horns calling like birds in April. But there was an ominous tone to it, too, a frisson of strings that seemed to hint that winter’s power still reigned supreme, and spring might have come prematurely.

Rogi felt himself relaxing, his eyes closing …

He saw a bleak and frostbound woodland, and beyond it a frozen river. On its opposite bank was an ancient Russian walled town. The moon was setting, and dawn had broken. Cocks crowed. As the heavens brightened, it seemed that millions of birds winged through the air toward the forest, finishing their long journey from the south. A little faun sat on the root of a hollow tree, watching the spectacle happily. He sang that Spring would be arriving at any moment.

And then she came, carried down in a green-and-golden chariot drawn by swans and geese, surrounded by other colorful singing birds. She began to tell Rogi a strange musical story.

Spring had once fallen in love with King Winter and borne him a daughter, the lovely Snow Maiden, Snegurochka. But Winter kept the girl in his power, taking her away each springtime to the dreary Northland that never thawed. Now that she was sixteen, the Snow Maiden longed to live with human beings, away from her coldhearted father’s domination.

Suddenly the landscape that Rogi imagined was swept by a brisk snowstorm, and King Winter himself strode into the scene. Spring pleaded with him to let the lovely little Snow Maiden go free.

Winter agreed but gave a grim warning: If the girl should ever fall in love and have that love returned by a mortal, the jealous sun god Yarilo would slay her—for love and the sun’s warmth were akin, and both were forbidden to the Snow Maiden.

Then Snegurochka herself appeared.

Rogi realized that his eyes were wide open, and the illusion—could Teresa be creating it?—was suddenly penetrated by a living person. She was dressed in white robes trimmed with snowy fur and seemed to sparkle with silvery frost crystals.

And Teresa was singing—really singing again, as she had in her prime—her marvelous living voice somehow blending seamlessly with the recorded orchestra and the other singers. All the magic that had seemed to be lost forever was

restored, and Rogi sat paralyzed in the midst of its glory, almost unwilling to believe that it was not part of the illusion.

The Snow Maiden rejoiced that she was to be allowed into the human world. She had seen a young man and fallen in love with him and the songs he sang. The very sound of his voice made her heart melt. “Melt!” cried King Winter, and warned her of her fate if she should have her love returned. But she could think only of the happiness that lay ahead of her.

Winter went off to his icebound lair, and Spring transformed the woods. The tiny Ape Lake cabin seemed to open wide into a huge green meadow full of flowers, and the delighted Snow Maiden was caught up in a mob of happy villagers, who danced and sang and welcomed her and took her home with them.

And the imaginary curtain fell on the Prologue …

Teresa stood there between the two glowing lamps, smiling at Rogi. Her splendid white gown and headdress were diminished, Cinderella-like, into ordinary cotton flannelette trimmed with the fur of snowshoe hares, with spangles and snowflakes cut from shiny foil. But she was still beautiful, still full of triumphant magic.

“Do you like the opera so far?” she asked.

“C’est fantastique!” Rogi cried. “But how are you projecting the illusion? I didn’t think your creative metafunction was up to such elaborations.”

“It’s not. But Jack’s is.”

“The

baby …”

“He finds the sets and the appearance of the other characters in my memories, and he realizes them. And now … Act One!”