Jacky Daydream (8 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

They took dance nights seriously. My dad wore a proper suit and tie and his black patent dancing shoes and my mum wore a sleeveless flowery chiffon frock with a sweetheart neckline. I wore my best embroidered party frock. So long as I behaved myself, I was allowed to stay up for the dance too. I hadn’t been taught to waltz or quickstep but I was good at following if someone steered me around, and sometimes my dad let me stand on his shiny shoes and we’d twirl round the ballroom together, stepping in perfect unison.

Will Tull varied dances, announcing Paul Jones swap-your-partner spots and invitation waltzes and Gay Gordons. There was always a conga at the end

of

the evening. Every single guest stepped and tapped around the ballroom, through the empty dining room, around the kitchens, out into the gardens, across the tennis courts . . . I think if Will Tull had led us down the road, across the esplanade, over the sands and into the sea, we’d have all followed.

The only entertainment I hated was talent night. My dad sensibly steered well clear of this one. My mum did the one and only recitation she knew by heart, ‘The Lion and Albert’, with a fake northern accent. This was strange, because she normally detested accents of any sort. She was so worried I’d ‘pick up’ a Lewisham south London twang and drop my aitches like ’ankies that she started sending me to elocution lessons at

four

. Mercifully, there was no ‘How now, brown cow’ twaddle. We learned poems instead.

I was the littlest and I had a good memory so it was easy for me to shine. My entire elocution class was entered for a public competition. We chanted an interminably long poem about birds. I was the Yellow Hammer. I had to pipe up, ‘A little bit of bread and no cheese!’ It went down a treat.

Biddy bought me an A. A. Milne poetry book. (I didn’t catch up with Winnie-the-Pooh until much later. When I made friends with a child called Cherry whose parents called her Piglet and her

sister

Pooh, I didn’t understand and thought they were very rude nicknames, if not downright insulting.)

I soon learned a lot of the poems and recited ‘

What

is the matter with Mary Jane?’ at the talent contest the first year at Waverley Hall. I did it complete with ghastly little actions, hands on hips, shaking my head, pulling faces. It was enough to make a sane person vomit but I got loud applause. Biddy was in seventh heaven. She’d always longed for a child like Shirley Temple. She had my wispy hair permed into a grisly approximation of those abundant curls and encouraged me to perform when I was even shyer than my father.

The second Waverley Hall holiday I knew the whole of ‘The King’s Breakfast’ by heart. Oh dear, I’ve not looked at it since but I’ve just gone over it in my head and I still know every awful line.

I was scared of performing it in public in front of everyone. I fidgeted nervously throughout our evening meal, going over the poem again and again in my head. I’d got sunburned on the beach and I felt hot and headachy. I gulped down glass after glass of cold water. A big mistake.

Straight after dinner the child performers in the talent contest were herded off to the little room behind the stage in the ballroom. I didn’t get a chance to visit the lavatory. I soon realized

I

badly needed to go. I was far too shy to tell anyone. I didn’t have enough gumption to go off and find a loo myself. I just sat with my legs crossed, praying.

Will Tull had decided to put me on almost at the end because I’d been such a success the year before. I waited and waited and waited, in agony. Then at long long last it was my turn. I shuffled on stage, stood there with clasped hands, head up, chest out, toes slightly turned out, in perfect elocution class stance.

‘“The King’s Breakfast” by A. A. Milne,’ I announced clearly.

A little ripple of amusement and anticipation passed through the audience. I relaxed. An even worse mistake.

‘The King asked

The Queen, and

The Queen asked

The Dairymaid:

“Could we have some butter for

The Royal slice of bread?”’

I declared, as I felt a hot trickle seep down my legs into my snowy white socks.

I didn’t stop. I didn’t run off stage. I carried on reciting as a puddle spread around my feet. I said

the

last line, bowed, and then shuffled off in soggy despair.

Biddy came and found me and carted me off to get changed. I wept. She told me that no one had even noticed, which was an obvious lie. I’d seen Will Tull follow me on stage with a

bucket and mop

. Biddy switched tack and said everyone simply felt sorry for me. I’d heard the ‘aaahs’ myself, so knew this was partly true, but I’d also heard the sniggers from the other children. I was sure they’d make my life hell the next morning at breakfast.

‘We have to go

home

! Please please please let’s go home,’ I begged.

Biddy and Harry scoffed at me.

‘But they’ll all tease me and laugh at me and call me names,’ I howled.

‘Don’t be so silly. They’ll have forgotten all about it by tomorrow,’ said Biddy.

This seemed to me nonsense. However, no one stared or whispered when we came down to breakfast the next morning. The children didn’t breathe a word about it, not even when we were playing in the ping-pong room without adult supervision. I couldn’t understand it. Maybe Will Tull had scurried from room to room and implored everyone to be kind, though this seems highly unlikely. Maybe my mum was right and they really had forgotten. Hadn’t even noticed. Whatever.

We carried on our Clacton holiday as usual. We sat on the sands all morning, Biddy and Harry in deckchairs, me cross-legged on a towel, reading or colouring or making sand palaces for my pink plastic children. We had our favourite spot, reasonably near the pier so we could stretch our legs and visit the lavatories, but not so near that the strange, dank, rotting-seaweed, under-the-pier smell tainted our squash and sandwiches.

There were amusement arcades on the pier. I didn’t care for them particularly, but Harry loved pinball and Biddy proved surprisingly expert on the crane machines. In one week’s holiday she could manoeuvre fifty or sixty toy planes and tiny teddies and Poppit bracelets and packets of jacks and yoyos and pen-and-pencil sets out of those machines, enough for several Christmas stockings for friends’ children.

There was a theatre at the end of the pier. I didn’t like the journey right along the pier to this theatre. I hated it when the beach finished and the sea began. You could see right through the wooden planks to where the water frothed below. My heart thudded at every step, convinced each plank would splinter and break and I would fall right through.

I cheered up when we got to the theatre and watched the summer season variety acts. I liked the dancers in their bright skimpy outfits, kicking

their

legs and doing the splits. My parents preferred the stand-up comedians, especially Tony Hancock. When

Hancock’s Half Hour

started on the radio, they listened eagerly and shushed me if I dared say a single word.

We went to Clacton year after year. We had a lovely time. Or did we? I always got over-excited that first day and had a bilious attack, throwing up throughout the day and half the night. Biddy would sigh at me as if I was being sick on purpose, but Harry was always surprisingly kind and gentle and would hold my forehead and mop me up afterwards. It’s so strange, because when I was bright and bouncy he’d frequently snap at me, saying something so cruel that the words can still make me wince now. I was always tense when he was around. I think Biddy was scared of him too at first. She used to cry a lot, but then she learned to shout back and started pleasing herself.

There was always at least one major row on holiday, often more. They’d hiss terrifying insults at each other in our bedroom and not speak at the breakfast table. My tummy would clench and I’d worry that I might be sick again. I’d see other families laughing and joking and being comfortably silly together and wish we were a happy family like that. But perhaps if I’d looked at

us

another day, Biddy and Harry laughing together, reading me a

cartoon

story out of the newspaper, I’d have thought

we

were that happy family.

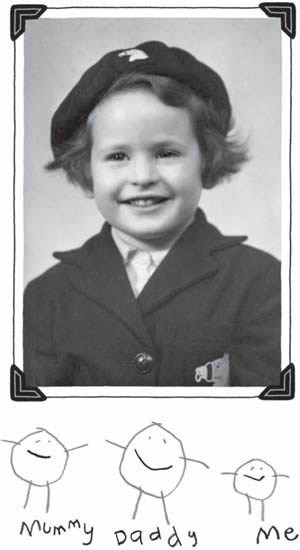

In the days before everyone had ordinary cameras, let alone phone and digital cameras, you used to get special seaside photographers. They’d stand on the esplanade and take your photo and then you could come back the next day and buy it for sixpence or a shilling.

There are two very similar such photos taken the Clacton holiday I was six – but they’re so very different if you look closely. The first caught us unawares. It’s a cloudy day to match our mood. My father looks ominously sulky in his white windcheater, glaring through his glasses. My mother has her plastic raincoat over her arm and she’s clutching me by the wrist in case I dart away. I’m looking solemn in my playsuit and cardigan, holding a minute bucket and spade and a small doll. I am wearing my ugly rubber overshoes for playing in the sand. I do not look a prepossessing child.

Biddy berated Harry and me for spoiling that photograph and insisted we pose properly the next day. The sun is out in the second photograph and we look in a matching sunny mood. Harry’s whipped off his severe glasses and is in immaculate tennis whites. Biddy’s combed her perm and liberally applied her dark red lipstick. I’m wearing my favourite pink flowery frock with a little white collar

and

dazzlingly white sandals. I’ve just been bought a new pixie colouring book so I look very pleased. Biddy is holding my hand fondly. Harry has his arm round her. We look the happiest of families.

This is an easy question. In which of my books does a little girl wet herself on stage?

It’s

Double Act

, my book about identical twins Ruby and Garnet.

They are jointly reminiscing about the time they played twin sheep in the school Nativity play. Ruby is being mean, teasing Garnet about it, even though she knows it’s her most painful and humiliating secret.

She got so worked up and nervous when we had to perform on stage that she wet herself. On stage. In front of everyone. But it didn’t really

matter

. I don’t know why she still gets all hot and bothered if I happen to bring

it

up. It was dead appropriate, actually, because that’s what real sheep do all the time. They don’t hang around the stable with their back legs crossed, holding it in. They go all over the place. Which is what Garnet did. And everyone thought it was ever so funny. Except Garnet.

I longed for brothers and sisters when I was a child. I particularly wanted a twin sister, someone to play with all the time, someone to whisper to at night, someone to cuddle when Biddy and Harry were yelling.

I can see it could have disadvantages though if you have a very bossy dominant twin like Ruby!

11

School

I CAN’T REMEMBER

my first day at Lee Manor School. I asked my mother if I cried and she said, shrugging, ‘Well, all children cry when they start school, don’t they?’