Jessen & Richter (Eds.) (53 page)

Read Jessen & Richter (Eds.) Online

Authors: Voting for Hitler,Stalin; Elections Under 20th Century Dictatorships (2011)

nearby while music was playing. After the former chairman of the works council

opened the assembly, making a short speech, the other officials of the former

works council reported on their activities. The chairman of the election commis-

sion read out the election procedure. The most important thing, he said, was that somebody who was not happy with a candidate is allowed to cross out the name

and can write another [name] next to it. This was also reported in the trade union periodicals. But what they did not mention was that you need a

pencil

for doing so,

——————

65 Thus, for example, extended rights of works committees regarding participation in decisions of works management were provided for by law on July 8, 1959. As of summer 1964, the State Wage Commission began to dismantle these rights again since, in the commission’s view, they were weakening the “authority” of industrial managers. Vgl.

VOA, ÚRO-Před., box 70, no. 405 I/5.

202

P E T E R H E U M O S

which not everybody has on him. And is it really secret when the lists of candidates are distributed immediately before the elections and if you want to cross out a

candidate—should a pencil be actually available—you would have to do it

right

under the nose of the comrades sitting next to you

? They will have something to talk about, and they are right! And what serious consequences all this will have! Since there is no discussion, the comrades leave the room where the election takes place early

and bitterly whisper in some corner or other saying that people do not like to leave a warm nest. We have to permit criticism without any consequences for those who

utter it, and exactly that does not happen in our case. Only then will we have a clean record and can tackle our daily work with pride.

The workers of the repair workshop of the Czechoslovak State Railways in

Chomutov

(VOA, ÚRO-Org., box 146, no. 484. Italics as per the [hand-written] original

letter.)

Bibliography

Dvořák, Stanislav (1969). Postoje pracujících pardubických podniků k podnikové

samospravě [Views of staff members of enterprises in Pardubice on self-man-

agement of enterprises].

Odbory a společnost

, 3, 19–32.

Heumos, Peter (1981). Betriebsräte, Einheitsgewerkschaft und staatliche Unterneh-mensverwaltung. Anmerkung zu einer Petition mährischer Arbeiter an die

tschechoslowakische Regierung vom 8. Juni 1947.

Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas

, 2, 215–45.

— (2001). Aspekte des sozialen Milieus der Industriearbeiter in der Tschecho-

slowakei vom Ende des Zweiten Weltkrieges bis zur Reformbewegung der

sechziger Jahre.

Bohemia,

2, 323–62.

— (2004). Stalinismus in der Tschechoslowakei. Forschungslage und sozialge-

schichtliche Anmerkungen.

Journal of Modern European History

, 2, 82–109.

— (2005a). Zum industriellen Konflikt in der Tschechoslowakei 1945–1968. In

Peter Hübner, Christoph Kleßmann, and Klaus Tenfelde (eds.).

Arbeiter im

Staatssozialismus. Ideologischer Anspruch und soziale Wirklichkeit

, 473–97. Cologne: Böhlau.

— (2005b). State Socialism, Egalitarianism, Collectivism: On the Social Context of Socialist Work Movements in Czechoslovak Industrial and Mining Enterprises,

1945–1968.

International Labor and Working-Class History

, 68, 47–74.

— (2007). Betriebsräte, Betriebsausschüsse der Einheitsgewerkschaft und Werk-

tätigenräte. Zur Frage der Partizipation in der tschechoslowakischen Industrie

vor und im Jahr 1968. In Bernd Gehrke and Gerd-Rainer Horn (eds.).

1968 und

die Arbeiter. Studien zum “proletarischen” Mai in Europa

, 131–59. Hamburg: VSA-Verlag.

W O R K S C O U N C I L E L E C T I O N S I N C Z E C H O S L O V A K I A 203

— (2008a). Arbeitermacht im Staatssozialismus. Das Beispiel der Tschecho-

slowakei 1968. In Angelika Ebbinghaus (ed.).

Die letzte Chance? 1968 in Ost-

europa

, 51–60, 215–20. Hamburg: VSA-Verlag.

— (2008b). “Der Himmel ist hoch, und Prag ist weit!” Sekundäre Machtverhält-

nisse und organisatorische Entdifferenzierung in tschechoslowakischen Indus-

triebetrieben (1945–1968). In Annette Schuhmann (ed.).

Vernetzte Improvisationen. Gesellschaftliche Subsysteme in Ostmitteleuropa und in der DDR,

21–41. Cologne: Böhlau.

— (2008c) Zum Verhalten von Arbeitern in industriellen Konflikten. Tschecho-

slowakei und DDR im Vergleich bis 1968. In Roger Engelmann, Thomas

Großbölting, and Hermann Wentker (eds.).

Kommunismus in der Krise. Die Ent-

stalinisierung 1956 und die Folgen

, 409–27. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Kalinová, Lenka (1993). Ke změnám ve složení hospodářského aparátu ČSR v 50.

letech [On the changes in the composition of the economic apparatus in the

ČSR in the 1950s]. In Karel Jech (ed.).

Stránkami soudobých dějin. Sborník statí ke

pětašedesátinámhistorika Karla Kaplana

[Leafing through contemporary history.

Collection of essays on the 65th birthday of the historian Karel Kaplan], 149–

57. Praha: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

— (2007).

Společenské proměny v čase socialistického experimentu. K sociálním dějinám v letech

1945–1969

[Changes in society during the period of the Socialist experiment.

On social history in the years 1945–1968]. Prague: Academia.

Kaplan, Karel (2007).

Proměny české společnosti (1948–1960). Část první

[Changes in Czech society (1948–1960). Part one]. Prague: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

Maňák, Jiří (1995).

Komunisté na pochodu k moci. Vývoj početnosti a struktury KSČ vobdobí

1945–1948. Studie

[The Communists rising to power. Development of membership and structure of the KSČ in the period 1945–1948. Study]. Prague:

Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

Pauer, Jan (2008). Der Streit um das Erbe des “Prager Frühlings”. In Stefan

Karner, Natalja Tomlina, Alexander Tschubarjan (eds.).

Prager Frühling. Das

internationale Krisenjahr 1968

.

Beiträge

, 1203–16, Cologne: Böhlau.

Pernes, Jiří (1997).

Brno 1951. Příspěvek k dějinám protikomunistického odporu na Moravě

[Brno 1951. Contribution to the history of the anticommunist opposition in

Moravia]. Prague: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

Rezoluce ze závodů (1968) [Resolutions from the plants].

Odborář

, 7, 18–20.

Sbírka zákonů a nařízení Republiky československé

(1945, 1963, 1959) [Collection of laws and ordinances of the Czechoslovak Republic 1945, 1963, 1959].

Vondrová, Jitka, Jaromír Navrátil, and Jan Moravec (eds.). (1999).

Komunistická

strana Československa. Pokus o reformu (říjen 1967—květen 1968)

[The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia. Attempt at reform (October 1967 – May 1968)].

Prague/Brno: Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

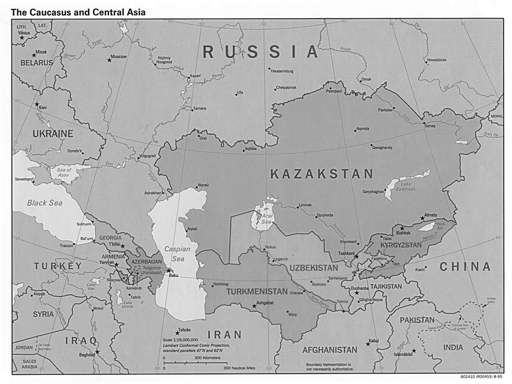

Faking It: Neo-Soviet Electoral Politics in

Central Asia

Donnacha Ó Beacháin

Post-Soviet Central Asian states are Potemkin democracies, which have

borrowed the form—but not the substance—of the Western systems they

claim to emulate. They have composed constitutions, using the best West-

ern advice, and established state institutions separated from one another

with clearly defined powers. There is a clear hierarchy of government with

often elaborate layers from the president through regions, towns, cities,

villages, and communities. Similarly, elections are held with due solemnity.

Announcements are made, campaigns are conducted, election commis-

sions established, vote counts held and victors announced. Elections, how-

ever, are often theaters of the absurd, in which each citizen is assigned an

acting role—the voter happily eschewing all alternatives to the status quo,

the president gratefully acknowledging yet another overwhelming vote of

confidence in his God-like powers. It is less an election than a ritual per-

formed to reaffirm faith in the president and the political system over

which he exercises absolute control.1

Though Central Asian regimes fit most neatly into the authoritarian

category defined by Linz (2000), some veer close to totalitarianism, com-

plying with at least one of its characteristics (elimination of opposition).

There has never been a peaceful transfer of power from government to

opposition and thus, employing Przeworski’s (2000) reasoning, they cannot

be considered democratic polities. If we use Levinsky and Way’s (2002,

51–56) definitions, Central Asian states, while of considerable variety, more

closely resemble “façade electoral regimes” (where electoral politics are a

sham thinly disguising outright dictatorships) than “competitive authori-

tarian” systems (where meaningful competition is permitted despite abuse

of administrative resources). Initially, many of the deficiencies were attrib-

uted to difficulties associated with the relatively sudden collapse of the

——————

1 This echoes what Jeffrey Brooks has called the “performative culture” inculcated during Soviet times (See Brooks 2000, xvi, xvii.).