Jitterbug (32 page)

Authors: Loren D. Estleman

Tags: #Historical, #Detroit (Mich.) - Fiction, #Detective and Mystery Stories, #Police, #Historical Fiction, #World War; 1939-1945, #Michigan, #Detroit, #Fiction, #Mystery Fiction, #Police - Michigan - Detroit - Fiction, #World War; 1939-1945 - Michigan - Detroit - Fiction, #Detroit (Mich.), #General

Zagreb, bunched up with his squad and quartermaster’s men at the gate in the chain-link fence, had been forced to wait an endless minute for a corporal to show up with a key to the padlock. Canal had wanted to shoot it off, like in the movies, but Burke, ever the squads ground to common sense, had pointed out that if the bullet didn’t bounce off and kill one of them, it would almost certainly jam the lock so it couldn’t be opened without a hacksaw.

Then the gate was open and they were inside and spreading out to search among the columns of silent tanks, the detectives with their badge folders hanging out of their breast pockets to avoid getting themselves shot by the army. Zagreb could feel the hair on the back of his neck prickling his shirt collar. He hadn’t felt that since he was in uniform, hunting among the boxcars in the Penn Central railroad yard for a Jackson parolee who had raped and murdered a nurse on Cass. He knew how Frank Buck must have felt tracking a wounded predator into the bush.

He wished they’d turn off the siren. The tanks’ metal fittings, cooling from the day’s heat, made noises that might have belonged to a man clambering over them, and that constant hooting was no help in determining the difference. His knees and neck ached from squatting to peer between the tracks and hoisting himself up and craning to see above the turrets. He stopped often to change hands on his gun and mop his palm on his trousers. The butt grew slippery again almost immediately.

He stopped and held his breath. Several yards to his right he heard a noise that might have been a man sobbing. The sound broke off suddenly. In the aftermath he couldn’t be sure that it hadn’t been just the echo of the siren off a curved metal surface, like a propane tank ringing after a cherry bomb was set off. But then it shouldn’t have stopped, because the siren was still going. He moved that way.

He was having trouble keeping his bearings. It was like searching a cornfield with ten-foot stalks on all sides, obliterating the horizon. He put a hand against the side of a tank that was smaller than some of the others, no more than fourteen feet long, for rest and to consider his direction. He felt a slight vibration through the metal, as if something was moving across it. He looked up at the turret.

A dark flying figure blocked out the sky. He whirled to bring his gun around just as the full weight of the figure struck him and bore him to the ground. An arm went across his throat, choking off his cry. He struggled, tightened his grip instinctively on the .38, then another arm snaked across his front and something pricked him above his belt and jerked back in a hooking movement. It stopped, worrying at something; it was hung up in the strap of his holster. He braced a knee against the ground and shoved back with all his weight. The grip broke. He scrambled to his feet, stumbled against the fender of the tank, grabbed it for balance, and spun around, holding the revolver

He’d seen the face before, earlier than the police sketch. He didn’t know where. The young man had fallen into a sitting position on the torn earth with his back against the steel wheels of the neighboring tank. He’d struck his head; he shook it, then opened his eyes, looked around, and lunged for the shining steel bayonet that had fallen near his right foot.

“Stop!” Zagreb cocked the hammer.

Ziska froze with one arm extended. His eyes moved from side to side, and the lieutenant realized they weren’t alone. Canal and McReary had come around the corner of the tank with their guns out. At the opposite end of the long aisle between the vehicles all in line, Burke approached on the run, his long, revolver-carrying shadow stretching out in front. Shouts getting close, more running feet. The soldiers had heard Zagreb’s cry.

The man on the ground relaxed then, shrinking in on himself. His sleeve was torn, exposing the flesh where his arm lay limp and pale between his knees. He was a broken thing.

Zagreb said, “Hey.”

Ziska took a moment to respond. He looked up without lifting his chin.

“Pick it up.”

The lieutenant was no longer sweating. His skin was cool and he could feel through it the man’s emotions, the tension in the other detectives as they watched, the vibration of combat boots approaching. Burke, the fourth horseman, had caught up; he felt his heart thudding from the hard run. Ziska, visibly reassembling himself from his shattered pieces, was a dead ringer for his image in charcoal. He looked exactly as he had when Cathleen Dooley had seen him, just before he slaughtered two people in J. L. Hudson’s in the middle of a weekday afternoon in wartime Detroit.

Kilroy reached out tentatively. Then he scooped up the bayonet and braced his other hand on the ground to hurl himself forward.

Four guns barked and kept on barking until they clicked empty.

O

N A SULTRY

S

ATURDAY

in July 1943, Lieutenant Max Zagreb decided to devote his day off to doing nothing. That wore thin by afternoon, and he dug himself out from under a pile of pulp magazines—the slicks just reminded him of Ziska and his subscription-salesman cover—and went to see a movie.

The feature at the Fox was

Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man

, but he was mostly interested in seeing the newsreels. The war had busted wide open beginning on June 22, when B-24 Liberators from the Ford Willow Run plant carpet-bombed the Ruhr industrial valley, flattening German munitions factories from Recklinghausen to Antwerp. Then on July 10, America invaded Sicily, pouring onto the south coast from the Pantelleria jumping-off point and plowing inland behind Patton’s Seventh Army. Montgomery’s Eighth landed three days later. Caught between the Americans and British, the Italians began to retreat like Mussolini’s forehead. The Pathé cameras dwelt on teenage gunners poking bucket-size cartridges into boiler-size breeches, but the real story was that the war was being fought between Henry Ford and Alfried Krupp, wobbly-kneed old men with smelting furnaces for hearts. The capacity crowd applauded each dubbed-in explosion. Zagreb figured they were there for the air-conditioning.

The auditorium was silent through the next segment, a follow-up on the Detroit riots. Some of Governor Kelly’s 1,000 National Guardsmen were shown patrolling the littered streets with M-l rifles, backed up by five thousand federal troops in jeeps and armored cars dispatched by President Roosevelt, who on Monday, June 21, declared martial law in the city. Carpets of shattered glass glittered on the sidewalks and pavement, looted suits and dresses abandoned in the getaway rush festooned the sills of empty display windows, a group of patrolmen and civilian volunteers wearing special armbands were shown rocking an overturned Chevy coupe from side to side in an effort to right it. The narrators stentorian voice intoned the statistics for the two-day toot: thirty-four dead, nine of them colored; six hundred injured; property loss nearly two million dollars; one rumor of rape and murder on Belle Isle, false.

Missing from the newsreel were a number of details that Zagreb himself would never repeat, lest he risk both his job and his draft-exempt status. Four colored men removed from the Woodward Avenue streetcar by eight patrolmen on the promise of safe passage, then turned over to a white mob and beaten to death. A colored boy, unidentified, stomped and pummeled by a gang of white men and boys in T-shirts until his brains leaked out his ears on the front steps of the Federal Building. An eyewitness reported on camera the stoning and beating death of Joseph Horatiis, a white doctor answering a call in the riot area, by Negroes who dragged him from his car. No footage went to the carloads of rednecks armed with rifles and shotguns, quartering the streets for colored game like drunken deer hunters.

It was no wonder, caught (like the Italians) between the rape of Detroit and the liberation of Europe, the fate of a five-time killer (perhaps six; sheriff’s deputies in Washtenaw County had identified a body found in a patch of woods near Willow Run as a girl last seen attending a movie with a man whose description closely matched Ziska’s), tracked down and shot by police when he refused to surrender, barely made the national wires, and then only one paragraph.

He left the theater before the final confrontation between the Wolf Man and Frankenstein’s flattopped monster. It reminded him too much of his marriage. At Michigan, he was held up through two light changes by a procession of cars headed for Jefferson, part of a publicized memorial service on Belle Isle for the victims of the riots. It included rattletrap touring cars filled with armband-wearing members of Reverend White’s church and officials of Otis Saunders’ Double-V Committee, a Negro community group; Cadillacs and Lincolns containing the Junior League wives of automobile manufacturers; various motorists and passengers unknown, probably friends and family of the slain; Robert Leroy Parker Gitchfield’s unmistakable Auburn, Gidgy at the wheel showing more brotherly regard than Zagreb would have expected of the most notorious black marketeer in Paradise Valley—and wasn’t that Beatrice Blackwood, the Forest Club’s most popular barmaid, riding shotgun?—and a couple in a battered Model A, colored kid with a face that looked like it was still healing from the events of last month, and his pretty light-colored girlfriend, both dressed in black. Zagreb felt vaguely certain he’d met the young man recently.

It bothered him, not that it should have. He came into contact with so many people in the course of an investigation; nobody could expect him to remember them all. They didn’t all look alike to him. He prided himself on that.

Loren D. Estleman (b. 1952) is the award-winning author of over sixty-five novels, including mysteries and westerns.

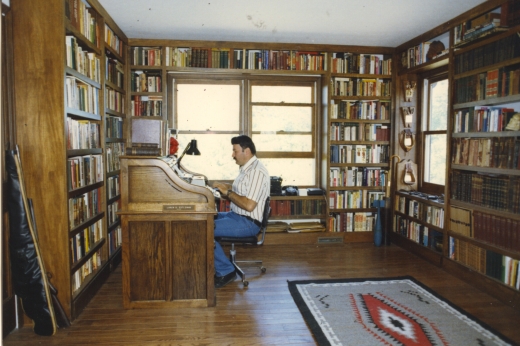

Raised in a Michigan farmhouse constructed in 1867, Estleman submitted his first story for publication at the age of fifteen and accumulated 160 rejection letters over the next eight years. Once

The Oklahoma Punk

was published in 1976, success came quickly, allowing him to quit his day job in 1980 and become a fulltime writer.

Estleman’s most enduring character, Amos Walker, made his first appearance in 1980’s

Motor City Blue

, and the hardboiled Detroit private eye has been featured in twenty novels since. The fifth Amos Walker novel,

Sugartown

, won the Private Eye Writers of America’s Shamus Award for best hardcover novel of 1985. Estleman’s most recent Walker novel is

Infernal Angels

.

Estleman has also won praise for his adventure novels set in the Old West. In 1980,

The High Rocks

was nominated for a National Book Award, and since then Estleman has featured its hero, Deputy U.S. Marshal Page Murdock, in seven more novels, most recently 2010’s

The Book of Murdock

. Estleman has received awards for many of his standalone westerns, receiving recognition for both his attention to historical detail and the elements of suspense that follow from his background as a mystery author.

Journey of the Dead

, a story of the man who murdered Billy the Kid, won a Spur Award from the Western Writers of America, and a Western Heritage Award from the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In 1993 Estleman married Deborah Morgan, a fellow mystery author. He lives and works in Ann Arbor, Michigan.

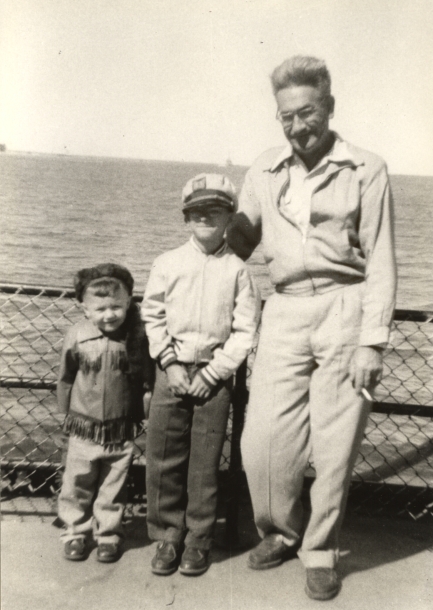

Loren D. Estleman in a Davy Crockett ensemble at age three aboard the Straits of Mackinac ferry with his brother, Charles, and father, Leauvett.

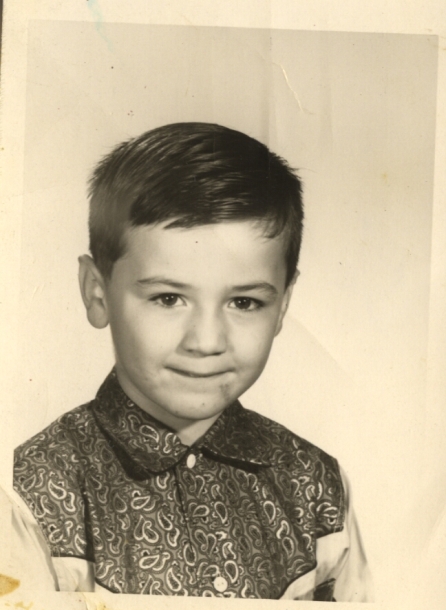

Estleman at age five in his kindergarten photograph. He grew up in Dexter, Michigan.

Estleman in his study in Whitmore Lake, Michigan, in the 1980s. The author wrote more than forty books on the manual typewriter he is working on in this image.