Read John Donne - Delphi Poets Series Online

Authors: John Donne

John Donne - Delphi Poets Series (57 page)

Saint Ambrose extols this act by many glorious circumstances; for instance, “That he flung away his shield, which might have sheltered him, so that, despising death, he forced his way into the midst of the army.” Also, “Being hemmed in rather than overwhelmed by catastrophe, he was buried in his triumph.” Again, “By death he begat peace as the heir of his valor.”

Very many scholastics have stretched and exercised their wits in praise of this action. Cajetan gives a reason for it that as is applicable to very many self-homicides: “To expose ourselves to certain death, if our first aim is not our own death but the common good, is lawful. For,” he says, “our actions that may be morally good or bad must be judged to be such by the reason that first motivates them, not by any accident, concomitance, accompaniment, or succeeding of them, although necessarily.” This decision of Cajetan’s will include many cases and instances that are condemned headlongly by intemperate censures.

9. The fall of Razis, our last example, is reported as follows. “He was beseiged and set afire. Willing to die manfully and to escape reproach that would be unworthy of his house, he fell upon his sword. In haste, he missed his first stroke and threw himself from the castle wall. Still, he got up again and ran to a high rock, took out his own bowels, and threw them among the people, calling upon the Lord of life and spirit. So he died” (II Macc. 14:41-46 excerpted).

This act the text does not accuse. Saint Thomas Aquinas accuses it of nothing except cowardliness, which Aristotle also imputes to this manner of dying, as we said before. Either Aquinas then spoke serviceably and advantageously to the point that he had in hand, or else he spoke for the most part, because for the most part infirmities provoke men to this act.

Saint Augustine, who argued as earnestly as Aristotle that this act is not one of greatness of mind, confesses that it was just that in Cleombrotus who, simply upon reading Plato’s

Phaedo,

killed himself. Said Augustine, “When no calamity urged him, no crime either true or imputed, nothing but greatness of mind moved him to apprehend death and to break the sweet bands of this life.” To be sure, he added that “It was done rather greatly than well.” But we now are seeking only the concession that sometimes there is in this act greatness and courage. What moved Aristotle and all the rest to be loath to cite too many cases was to quench in men their natural love of self-homicide.

For Augustine says, “Except for Lucrecia, it is not easy to find any example worth prescribing or imitating—except Cato, not only because he did it but because, being reputed learned and honest, men might justly think that what he did was well done and might well be done again.” For all this, he is loath to let Cato’s act pass with much approbation, for he adds, “Yet many of his learned friends thought it a weakness to let him die thus.” He adds it because, when men have before them the precedent of a brave example, they do not ask further than

what

he did—not

why

he did it.

It is truly said, “Examples do not stop, nor do they consist in the degree where they began, but they grow, and no man thinks that what has profited another is unworthy for himself.” Saint Augustine, for this reason loath to give glory to many examples, still allows all greatness and praise to Regulus, of whom we spoke before—even though, to my understanding, there are in this example many impressions of falsehood and of ostentation, from all of which Cato’s story is free.

To conclude this point, whether it is always done from cowardliness, Diogenes Laertius says that “Antisthenes the philosopher seemed to show more weakness in that, lying extremely sick, and Diogenes asking him if he lacked a friend (meaning to kill him) and also offering his dagger to do it himself, the philosopher said he desired an end of pain but not of life.”

Since the self-homicide of Razis may have proceeded from greatness, Nicholas of Lyra excused it from all sin, by reasons that are applicable to many others. He says, “Either to escape torment, by which a man might probably be seduced to idolatry, or to take away the occasion of making others reproach God in him, a man may kill himself, for both of these cases are ordained by God.” Francisco de Vitoria allows this as the more probable opinion. Soto and Valencia follow Aquinas’s opinion. Paul of Burgos condemns it on the presumption that he could not do it for the love of the common good, because the act could not redeem his people who were already captive. Paul of Burgos’s accusing him helps our case in that, if by his death he could have redeemed them, he might lawfully have done it.

CONCLUSION

This is as far as I allowed my discourse to progress in this way, forbidding it earnestly all dark and dangerous withdrawals and diversions into points of our free will and God’s destiny. Still, allowing many ordinary contingencies to be under choice, it may seem reasonable that our main periods—of birth, death, and major alterations—in this life are more immediately worked upon by God’s determination. It is usefully said and applicable to good purpose (although by a wicked man, Muhammad, with the intention of crossing Moses) that “Man was made of shadow and the devil of fire.” For as shadow is not darkness but grosser light, so is man’s understanding in these mysteries not blind but clouded. As fire does not always give light (for fire is accidental and must have air to work upon) but burns naturally, so the desire of knowledge that the devil kindles in us—he as willingly bellows to inflame a heart curious of knowledge as he brings more ashes to stupify and bury deeper a slumbering understanding—does not always give us light. But fire always burns us and imprints upon our judgment stigmatic marks, and at least it sears up our conscience.

If the reasons that differ from me and my reasons are otherwise equal, still theirs have this disadvantage; they fight with themselves and suffer a civil war of contradiction. For many of their reasons incline us to a love of this life and a horror of death, and yet they say often that we are by nature too much addicted to all that. It is well noted by Alcuin (I think from Saint Augustine) that “Although there are four things that we must love, yet there is no precept given concerning more than two, God and our neighbor.” Thus the others, which concern loving ourselves, may be omitted on some occasions.

Enough has been occasionally inserted above concerning the benefits of death. Having presented Cyprian’s encouragement to it—who out of a contemplation that the whole frame of the world decayed and languished, cries to us, “The walls and the roof shake, and would you not go out? You are tired in a pilgrimage, and would you not go home?”—I shall end by applying to death, which deserves it better, Ausonius’s thanks to the emperor, “You provide that your benefits and the good that you bring shall not be transitory and that the ills from which you deliver us shall never return.” So, because death has a little bitterness, but medicinally, and a little alloy, but to make it more useful, they would utterly decline and avert our nature from it.

Paracelsus says of that foul, contagious disease [i e., syphilis] that then had invaded mankind in a few places and has since overflowed into all places, God first inflicted that disease for the punishment of general licentiousness, and when the disease would not reduce us he sent a second and worse affliction, ignorant and torturing physicians. I may say the same of this case, that in punishment of Adam’s sin God cast upon us an infectious death, and since then he has sent us a worse plague of men who accompany death with so much horror and fright that it can hardly be made wholesome and agreeable to us. They teach with too much liberty what Hippocrates admitted in cases of much profit and little danger, “Worse meat may be given to a patient, if it is pleasanter, and worse drink, if it is more acceptable.”

I thought it needful to oppose this antidote—as much to encourage men toward a just contempt of this life and to restore them to their nature, which is a desire of supreme happiness in the next life through the loss of this one, as to rectify and wash again the frame of those who, religiously assuring themselves that in cases when we are destitute of other means, we might be to ourselves the stewards of God’s benefits and the ministers of his merciful justice.

These persons, being innocent within themselves, as Ennodius said, had incurred injury of opinion. Still, as I said before, I abstained intentionally from extending this discourse to particular rules or instances, both because I dare not profess myself a master in so curious a science and because the limits of the subject are obscure, steep, slippery, and narrow, and also because every error is deadly, except where a competent diligence has been employed and a mistake of our conscience may provide an excuse.

The curing of diseases by touch or by charms is forbidden by various laws, even though one excellent surgeon (Paracelsus) and one excellent philosopher (Pomponazzi) are of the opinion that it may be done—because man, who is all, is capable of whatever virtue the heavens infuse into any creature, and, being sustained when that virtue is exacted, may receive a similar impression or may give it to a word or character made at that instant. Although this curing is forbidden by various laws, because of a just prejudice that vulgar owners of such a virtue would misuse it, still none objects that the kings of England and France should cure one sickness by such a means, nor that the kings of Spain should exorcise demon-possessed persons in this way, because kings are justly presumed to use all their power to the glory of God. So it is fitting that this privilege of which we speak should be contracted and restrained.

That is certainly true of what Cassian says of a lie, “It has the nature of [the herb] hellebore, wholesome in desperate diseases but otherwise poison,” although I do not agree with him that, “We are in desperate diseases whenever we are in a state of great wealth or injury, and in humility to the shunning of vainglory.” However, if Cassian mistakes that and we this, yet as he, Origen, Chrysostom, and Jerome are excused for following Plato’s opinion that a lie might have the nature of medicine and be allowed in many cases (because in their time the church had not declared herself in that point nor pronounced that a lie was naturally evil), by the same reason I am excusable in this paradox.

If prejudice or contempt for my weakness or misdevotion has blocked any against the reasons for my case and against charity, such that they have not been pleased to taste and digest them, I must leave them to their drowsiness and bid them enjoy the favor of that indulgent physician, “Let him who cannot digest food sleep.”

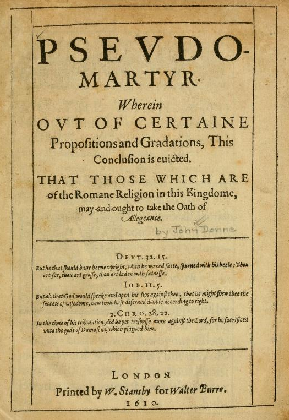

PSEUDO-MARTYR

This 1610 polemical tract argues that English Roman Catholics should take the Oath of Allegiance of James I of England. Donne had converted from Catholicism, but had not moved decisively into the Protestant camp. From 1604 he was involved in controversial theology as an onlooker, assisting his friend Thomas Morton in a reply to James Anderton, commissioned by Richard Bancroft. In publishing this work, Donne entered directly into one of the major debates of the period, supporting Sir Edward Coke against the Jesuit Robert Parsons.

Pseudo-Martyr

launched Donne’s career in the Church of England, establishing his name as one of the prominent religious thinkers of the time.

With regret, no transcription of the text is available in the public domain, so the text cannot appear in this eBook. However, readers can access an original publication of the text for free via this

weblink

.

The original frontispiece

IGNATIUS HIS CONCLAVE