John Quincy Adams (15 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

Pickering asked John Quincy to travel to London in the absence of American minister Thomas Pinckney to execute the formal exchange of signed copies of the Jay Treaty with the British government. Pinckney had gone to Spain to negotiate a treaty giving Americans navigation rights on the Mississippi River.

When the terms of the Jay Treaty became known in America in March 1795, Washington loyalists hailed Jay for averting another brutal war with England and forcing Britain to deal with the United States for the first time as an equal and independent sovereign state. But as Washington and Jay both knew it would, the treaty provoked a storm of controversy over what it did not accomplishâespecially among advocates for states' rights, Francophiles, and Anglophobes, all of whom attacked the treaty as pro-British. Washington loyalists in the Senate, however, outnumbered opponents, and the Senate ratified the treaty on June 24âironically, just as Jay himself slipped away from the fray over foreign affairs by winning election as governor of New York.

By then, the savagery of the French Revolution had eroded popular support for the French in America, while the Jay Treaty with Britain was producing economic benefits. In the West, Britain's troop pullback into Canada had ended the flow of arms to hostile Indians. Without British military support, the Indians ceded most of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Michigan to the United States, ending Indian forays in the West and opening the vast Ohio and Mississippi river valleys to American settlement. Meanwhile, Thomas Pinckney won Spain's agreement to free Mississippi River navigation for Americans and to allow them to deposit goods in New Orleans for export overseas. Elated by the prospects of a western economic boom, Americans quickly forgot their objections to the Jay Treaty.

Although John Quincy had set out for England on October 20 to exchange copies of the signed treaties, ill winds and a variety of dockside misunderstandings prevented his reaching London until November 11, by which time Pinckney's secretary had completed the transaction. All that remained was the ceremonial presentation of the document to the king. Early in December, British undersecretary of foreign affairs George Hammond,

a cunning and vicious anti-American whom John Quincy knew from the 1783 Paris peace talks, summoned Adams to his office. Although Hammond had been England's first minister to the United States in 1791 and had married a Philadelphian, his efforts to undermine the American government seemed to know no bounds. He lost no time trying to trap John Quincy in an indiscretion by asking if he had heard of the President's “intending to resign” in the wake of the Genet affair.

a cunning and vicious anti-American whom John Quincy knew from the 1783 Paris peace talks, summoned Adams to his office. Although Hammond had been England's first minister to the United States in 1791 and had married a Philadelphian, his efforts to undermine the American government seemed to know no bounds. He lost no time trying to trap John Quincy in an indiscretion by asking if he had heard of the President's “intending to resign” in the wake of the Genet affair.

“No!” John Quincy replied simply and sharply.

“What sort of a soul does this man suppose I have?” John Quincy confided to his diary that night. “He talked of Virginians, the southern people, the Democrats, but I let him know that I consider them all in no other light than as Americans.” He asked whether Pinckney had worked out an agreement with Spain, then hammered John Quincy with rumors of a political revolt against George Washington. John Quincy deftly parried Hammond's thrusts.

“All governments have their opposition who find fault with everything,” John Quincy said nonchalantly. “Who has better reason to know that than you in this country?” he smiled condescendingly. “But in America, you know, opposition speaks in a louder voice than anywhere else. Everything comes out; we have not lurking dissatisfaction that works in secret and is not seen, nothing that rankles at the heart while the face wears a smile so that a very trifling opposition makes a great show.”

16

16

“Hammond is a man of intrigue,” John Quincy reported in his diary. “His question whether Mr. Pinckney has signed the treaty in Spain, implies at least that he knows there was a treaty to sign. . . . If I stay here anytime, he will learn to be not quite so impertinent.”

17

Adams surmised that Hammond was either intercepting his mail or having him followed. He determined to be more discreet in what he did, said, and wrote.

17

Adams surmised that Hammond was either intercepting his mail or having him followed. He determined to be more discreet in what he did, said, and wrote.

In fact, Hammond's intelligence was better than John Quincy'sâand even better than that of Vice President John Adams. On January 5, a month after Hammond had met with John Quincy, John Adams wrote to Abigail, “I have this day heard news that is of some importance. It must be kept a secret wholly to yourself. One of the ministry told me that the

President was solemnly determined to serve no longer than the end of his present period. . . . You know the consequence of this to me and to yourself. Either we must enter into ardors more trying than any ever yet experienced or retire to Quincy, farmers for life. I am . . . determined not to serve under Jefferson. . . . I will not be frightened out of the public service nor will I be disgraced in it.”

18

President was solemnly determined to serve no longer than the end of his present period. . . . You know the consequence of this to me and to yourself. Either we must enter into ardors more trying than any ever yet experienced or retire to Quincy, farmers for life. I am . . . determined not to serve under Jefferson. . . . I will not be frightened out of the public service nor will I be disgraced in it.”

18

Far from expressing joy at her husband's thinking, Abigail quoted a warning from Charles Churchill's epic poem

Gotham

:

Gotham

:

You know what is before you: “the whips and scorpions, the thorns without roses, the dangers, anxieties and weight of empire”âand can you acquire influence sufficient as the poet further describes: “to still the voice of discord in the land”?

19

19

The day after meeting with Hammond, John Quincy presented his credentials to King George III before addressing him with prepared remarks: “Sir. To testify to your majesty the sincerity of the United States of America in their negotiations, their President has directed me . . . ” and he went on to give the king a copy of the Jay Treaty along with a letter from President Washington.

“To give you my answer, Sir,” the king responded with a typically noncommittal royal reply, “I am very happy to have the assurances of their sincerity, for without that, you know, there would be no such things as dealings among men.”

20

20

In France, however, the Directory responded angrily to the Jay Treaty, insisting it was a violation of “the alliance which binds the two peoples.” The French recalled their ambassador, and when the American government retaliated by recalling ambassador James Monroe, the French ordered seizure of all American ships sailing into French waters, with confiscation of all cargoes and imprisonment of American seamen for ransom.

While waiting for Pinckney's return to London, John Quincy went to hear debates at the House of Commons and visited Joshua Johnson, the wealthy Maryland merchant who lived near the Tower of London in a lavish

brick mansion, where he also served as American consul. Staffed by eleven servants, Johnson's home was a center of opulence and hospitality for visiting diplomats and other dignitaries. John Quincy had first met Johnson in 1781 as a fourteen-year-old, when he and his father were in Nantes, awaiting passage to America after John Adams's first diplomatic assignment in Paris. Johnson's three oldest daughtersâbarely more than infants when John Quincy first met themâhad blossomed into attractive young ladies. Burdened with four other, younger girls and a young son, the Johnsons were eager to marry off their three oldest, and they welcomed the son of America's vice president with great warmth. They invited him to their oldest daughter's birthday ball, where John Quincy “danced till 3 in the morning” and found “Mr. Johnson's daughters pretty and agreeable. The oldest performs admirably on the pianoforte; the second, Louisa, sings; the third plays the harp.”

21

brick mansion, where he also served as American consul. Staffed by eleven servants, Johnson's home was a center of opulence and hospitality for visiting diplomats and other dignitaries. John Quincy had first met Johnson in 1781 as a fourteen-year-old, when he and his father were in Nantes, awaiting passage to America after John Adams's first diplomatic assignment in Paris. Johnson's three oldest daughtersâbarely more than infants when John Quincy first met themâhad blossomed into attractive young ladies. Burdened with four other, younger girls and a young son, the Johnsons were eager to marry off their three oldest, and they welcomed the son of America's vice president with great warmth. They invited him to their oldest daughter's birthday ball, where John Quincy “danced till 3 in the morning” and found “Mr. Johnson's daughters pretty and agreeable. The oldest performs admirably on the pianoforte; the second, Louisa, sings; the third plays the harp.”

21

Evidently enchanted by the three girls, he spent part of almost every succeeding day or evening in January with the Johnsons, playing cards, walking in the park, and accompanying them to theater, concerts, and balls. Although the Johnsons expected he would marry their oldest daughter, John Quincy surprised the entire family on February 2, 1796, by telling twenty-year-old Louisa Catherine, the Johnsons' second daughter, that he intended to marry her.

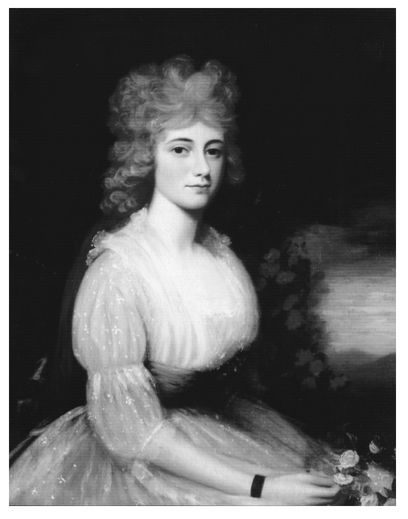

Louisa was beautiful, cultured, and fluent in French, the language of diplomats. Musically talented, elegant in dress, bearing, and manners, she was quiet and respectful in the presence of gentlemen and a lively conversationalist when appropriate. And she was comfortable among the rich and powerful. For John Quincy, a rising star in the diplomatic world, Louisa Catherine Johnson, the English-born daughter of an American diplomat, seemed a perfect match.

In his letters home, John Quincy only hinted of a liaison at first, without identifying Louisa. Fearing her son's intended was English and would destroy his prospects for political success in America, Abigail fretted, “I would hope for the love I bear my country, that the siren is at least

half-blood

.”

22

With memories of Bunker's Hill and the Boston occupation

swirling in her head, Abigail still despised the British. John Quincy's father was more philosophical than his wife, however. “Alas! Poor John!” he remarked to Abigail. “If the young man really loves her, I will not thwart him. . . . Ambition and love live together well. . . . A man may be mad with both at once. . . . His father and his mother too know what it is. . . . Witness Caesar and Anthony with Cleopatra and many others.”

23

half-blood

.”

22

With memories of Bunker's Hill and the Boston occupation

swirling in her head, Abigail still despised the British. John Quincy's father was more philosophical than his wife, however. “Alas! Poor John!” he remarked to Abigail. “If the young man really loves her, I will not thwart him. . . . Ambition and love live together well. . . . A man may be mad with both at once. . . . His father and his mother too know what it is. . . . Witness Caesar and Anthony with Cleopatra and many others.”

23

Â

Twenty-year-old Louisa Catherine Johnson, the English-born daughter of the American consul in London, caught John Quincy Adams's eye, and he proposed marriage to her in February 1796.

(PORTRAIT BY EDWARD SAVAGE, NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

(PORTRAIT BY EDWARD SAVAGE, NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

A letter from John Quincy eventually calmed both their fears:

Your apprehensions as to the tastes and sentiments of my friend [were] perfectly natural, and all your observations on the subject were received by me with gratitude, as I know them to proceed from serious concern

and the purest parental affection. . . . But she has goodness of heart and gentleness of disposition as well as spirit and character and with those qualities, I shall venture upon the chances of success and hope you will find her . . . such a daughter as you would wish for your son.

24

and the purest parental affection. . . . But she has goodness of heart and gentleness of disposition as well as spirit and character and with those qualities, I shall venture upon the chances of success and hope you will find her . . . such a daughter as you would wish for your son.

24

Moved by his letter, Abigail answered contritely, “I consider her already as my daughter.” She went on to ask for a miniature portrait and lock of her future daughter-in-law's hair.

25

John Adams also sent his blessing, telling his son, “You are now of age to judge for yourself; and whether you return [to England] and choose her or whether you choose elsewhere, your deliberate choice will be mine.”

26

25

John Adams also sent his blessing, telling his son, “You are now of age to judge for yourself; and whether you return [to England] and choose her or whether you choose elsewhere, your deliberate choice will be mine.”

26

Although Louisa had wanted to marry immediately, John Quincy refused, insisting he could not consider marriage until he was financially secure. His salary, he insisted, was not enough to afford proper lodgings for a minister and his wife, let alone a wife used to luxuries. His plan was to finish his three-year assignment in Holland and, in 1797, return to Massachusetts, reestablish his law practice, and then marry. A month after John Quincy had proposed, he spent one last “evening of delight and of regret, and I took my leave of the [Johnson] family with sensations unusually painful.”

27

27

“On my return from England,” he wrote in his diary, “I determined to resume a life of applications to business and study,”

28

and, indeed, he reveled in the calm and relaxation of intense, solitary study. “To improve in the Dutch language, I have usually translated a page every day. . . . My progress in Italian is slow. . . . The language is enchanting. . . . To keep alive my Latin, I have begun to translate a page of Tacitus every day . . . into French.”

29

28

and, indeed, he reveled in the calm and relaxation of intense, solitary study. “To improve in the Dutch language, I have usually translated a page every day. . . . My progress in Italian is slow. . . . The language is enchanting. . . . To keep alive my Latin, I have begun to translate a page of Tacitus every day . . . into French.”

29

His official duties seldom required more than a few hours a day. He wrote to the

Leyden Gazette

, for example, protesting an article asserting that “disgust at the ingratitude of the American people had induced General Washington to retire from his eminent station.” John Quincy asked the editor to “have the goodness to correct . . . an imputation both injurious to the President and people of the United States.”

Leyden Gazette

, for example, protesting an article asserting that “disgust at the ingratitude of the American people had induced General Washington to retire from his eminent station.” John Quincy asked the editor to “have the goodness to correct . . . an imputation both injurious to the President and people of the United States.”

The reasons assigned by the President himself for declining to be viewed as a candidate for the approaching election are his time of life, his strong inclinations towards a retired life, and the peaceable, calm and prosperous state of affairs in that country. . . . The imputation of disgust to General Washington and of ingratitude to the Americans is merely the calumny of English spirits beholding the felicity of the Americans.

30

30

As summer neared its end, John Quincy learned that George Washington had promoted him from minister to minister plenipotentiary, with a new assignment in Lisbon, Portugal, to begin in the spring of 1797. His salary would double to $9,000 a year and allow him an additional $4,500 a year for expensesâenough to marry Louisa and take her with him to his new post. The promotion was not only a reward for his good work and steadfast loyalty to the President's policies; it was the President's way of publicly demonstrating his confidence in John Quincy's diplomatic skills. Although reluctant to postpone his return to America by another three years, John Quincy agreed to take the post after his brother Thomas promised to go as well.

Other books

Love Unfurled by Janet Eckford

Darkness of the Soul by Kaine Andrews

Burying the Sun by Gloria Whelan

Ragamuffin by Tobias S. Buckell

Survival Games by J.E. Taylor

Murder and Marinara by Rosie Genova

Dragons Realm by Tessa Dawn

The Lives of Things by Jose Saramago

Children of the Cull by Cavan Scott

Bound by the Boss (BDSM Erotica) by Bailey, J.A.