John Quincy Adams (38 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

Later that fall, John Quincy rejoined Louisa in Washington, spending his time on walks, swimming in the Potomac, and writing articles on international affairs that found their way into scholarly journals. In the spring of 1830, he returned to Quincy, this time with Louisa, leaving John II in Washington to try to extract profits from the Columbian Mills flour business.

As the summer progressed, however, John Quincy fell deeper into depression, finding his only pleasures in walking and swimming, reading the Bible and Cicero's

Orations

, planting fruit trees, and tending a garden of

peas, beans, corn, and other vegetables. He made halfhearted attempts at organizing his father's papers, rummaging through boxes and finding some mementos of his youthâlargely books, such as a fondly remembered edition of

Arabian Nights

. “The more there was in them of invention, the more pleasing they were,” he recalled. “My imagination pictured them all as realities, and I dreamed of enchantments as if there was a world in which they existed.”

2

Charles Francis and his wife visited regularly for family clambakes, John II came up from Washington for two short visits, and the summer slipped away.

Orations

, planting fruit trees, and tending a garden of

peas, beans, corn, and other vegetables. He made halfhearted attempts at organizing his father's papers, rummaging through boxes and finding some mementos of his youthâlargely books, such as a fondly remembered edition of

Arabian Nights

. “The more there was in them of invention, the more pleasing they were,” he recalled. “My imagination pictured them all as realities, and I dreamed of enchantments as if there was a world in which they existed.”

2

Charles Francis and his wife visited regularly for family clambakes, John II came up from Washington for two short visits, and the summer slipped away.

As ill disposed as he was to public functions, he agreed to attend the bicentennial celebration of the founding of Boston on September 17, and to his surprise, two honorary marshals escorted him from the State House to the Old South Church. Well-wishers hailed him as he passed, and even former Federalist adversaries approached with warm salutations. At the end of the day, he attended a reception at the lieutenant governor's residence, where his friends, the Everett brothers and the editor of the Boston

Patriot,

were huddling with Quincy congressman Reverend Joseph Richardson. After greeting the former President, they asked if they could visit him the following day. He agreed, and at the appointed time, they informed him that Richardson's parishioners had pleaded with him to retire from Congress to devote himself full time to his church, and he had agreed. The Everetts then asked John Quincy to run for Richardson's seat, assuring him that he would win without opposition and flattering him with the notion of “ennobling” the House of Representatives with the presence of a former President.

Patriot,

were huddling with Quincy congressman Reverend Joseph Richardson. After greeting the former President, they asked if they could visit him the following day. He agreed, and at the appointed time, they informed him that Richardson's parishioners had pleaded with him to retire from Congress to devote himself full time to his church, and he had agreed. The Everetts then asked John Quincy to run for Richardson's seat, assuring him that he would win without opposition and flattering him with the notion of “ennobling” the House of Representatives with the presence of a former President.

Always in character, John Quincy feigned disinterest, saying he would do nothing to support his own candidacy. Explaining his familiar position on political campaigns, he asserted that if the people called on him of their own volition, he “might deem it my duty to serve. . . . I want the people to act spontaneously.”

3

He made it clear, however, that he would remain independent of party affiliations and represent the whole nation, with his only political loyalty tied to national independence from all foreign entanglements and preservation of the Union.

3

He made it clear, however, that he would remain independent of party affiliations and represent the whole nation, with his only political loyalty tied to national independence from all foreign entanglements and preservation of the Union.

Both Louisa and Charles Francis were appalled that John Quincy would even consider returning to politics after the humiliation he had suffered. Louisa threatened not to accompany him if he returned to Washingtonâto no avail. Quincy voted overwhelmingly to return their former President to Washington, giving him 1,817 votes, while the two other candidates garnered a combined total of only 552 votes.

“I am a member-elect of the Twenty-Second Congress,” he wrote in joyful disbelief that night, and nothing Louisa could say could detract from his satisfaction. “My return to public life . . . is disagreeable to my family,” he admitted, “yet I can not withhold my grateful acknowledgment to the Disposer of human events and to the people of my native region for this unexpected testimonial of their continued confidence.”

It seemed as if I was deserted by all mankind. . . . In the French opera of

Richard Coeur-de-Lion

, the minstrel Blondel sings under the walls of his prison a song, beginning:

Richard Coeur-de-Lion

, the minstrel Blondel sings under the walls of his prison a song, beginning:

O, Richard! O, mon Roi!

L'univers t'abandonne.

y

y

When I first heard this song, forty-five years ago . . . it made an indelible impression upon my memory, without imagining that I should ever feel its force so much closer to home. But this call upon me by the people of the district in which I reside, to represent them in Congress, has been spontaneous. . . . My election as President of the United States was not half so gratifying to my inmost soul. No election or appointment conferred upon me ever gave me so much pleasure.

4

4

As his spirits revived, he finally coaxed Louisa into returning to Washington, and the two left in December. Along the way, he showed himself still a champion of public improvements by being among the first to ride on the new steam-driven train between Baltimore and Washington. And

to his delight and Louisa's amazement, a crowd awaited to greet them on their return. Although he would not take his seat until 1832, three hundred callers came to their house on New Year's Day 1831, buoying his spirits still more and spurring him to seek out and meet members of Congress to determine their political views. He attended the House of Representatives to learn the rules and study member quirks and tics, and as he soaked up the thinking of his future colleagues, the joy of his return to politics spurred a renewed interest in scholarly pursuits, including poetry. By spring, when the time came to return to Quincy, he had reread

Childe Harold

,

Don Juan

, and other works of Lord Byronâand written his own epic, 2,000-line poem titled

Dermot MacMorrogh

, on Henry II's conquest of Ireland. He considered it his finest work and at least one publisher agreed, producing three successive editions.

z

On the way north, he stopped to see former President James Monroe, who was gravely ill in New York and destitute, living off the charity of his daughter and son-in-law at their New York City home.

to his delight and Louisa's amazement, a crowd awaited to greet them on their return. Although he would not take his seat until 1832, three hundred callers came to their house on New Year's Day 1831, buoying his spirits still more and spurring him to seek out and meet members of Congress to determine their political views. He attended the House of Representatives to learn the rules and study member quirks and tics, and as he soaked up the thinking of his future colleagues, the joy of his return to politics spurred a renewed interest in scholarly pursuits, including poetry. By spring, when the time came to return to Quincy, he had reread

Childe Harold

,

Don Juan

, and other works of Lord Byronâand written his own epic, 2,000-line poem titled

Dermot MacMorrogh

, on Henry II's conquest of Ireland. He considered it his finest work and at least one publisher agreed, producing three successive editions.

z

On the way north, he stopped to see former President James Monroe, who was gravely ill in New York and destitute, living off the charity of his daughter and son-in-law at their New York City home.

After his return to Quincy, town officials invited him to give the July 4 oration, and he set to work drafting a fierce attack on the doctrine of “nullification,” which had regained currency in the South in response to high federal tariffs on cotton goods. Thomas Jefferson had fathered the concept in 1798, when he was vice president and opposed the Alien and Sedition Acts of President John Adams. Declaring the Constitution only “a compact” among sovereign states, Jefferson insisted that the states retained authority to restrain actions by the federal government that exceeded its constitutional mandate. Jefferson persuaded the Kentucky legislature to approve a resolution allowing it to declare unconstitutional any federal government exercise of powers not specifically delegated by the Constitution. His protégé, James Madison, marched in lockstep and convinced the Virginia legislature “to interpose” its authority to prevent federal “exercise

of . . . powers” not granted by the Constitution.

5

Federalist legislatures in other states, however, declared the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions “mad and rebellious” and rejected them by declaring U.S. courts to be the sole judges of constitutionality.

of . . . powers” not granted by the Constitution.

5

Federalist legislatures in other states, however, declared the Virginia and Kentucky resolutions “mad and rebellious” and rejected them by declaring U.S. courts to be the sole judges of constitutionality.

Vice President John C. Calhoun subsequently revived southern interest in the concept with an essay he called “South Carolina Exposition and Protest.” In it, he insisted that the Tenth Amendment gave every state the right to nullify a federal act that it deemed a violation of the Constitution. In his July 4 oration in Quincy, John Quincy countered by labeling the concept of state sovereignty a “hallucination” and nothing “less than treason”âa fierce charge that resounded across the country after an enterprising printer distributed more than 4,000 copies of his speech nationwide.

As John Quincy delivered his oration, the President he had served for eight years died in New Yorkâjoining John Adams and Thomas Jefferson as the third of the first five Presidents to die on July 4. Asked to deliver a eulogy for Monroe at Boston's Old South Church, John Quincy produced a stirring reminder of Monroe's courage as an officer during the Revolution, “weltering in his blood on the field of Trenton for the cause of his country.” Then John Quincy turned to his ownâand Monroe'sâfavorite subject: public improvements. He urged mourners to “look at the map of United North America, as it was . . . in 1783. Compare it with the map of that same Empire as it is now. . . . The change, more than of any other man, living or dead, was the work of James Monroe.” John Quincy recalled how Monroe had scoffed at Congress for denying it had “the power of appropriating money for the construction of a canal to connect the waters of Chesapeake Bay with the Ohio.”

6

He portrayed the “unspeakable blessings” of Monroe's vision of a transnational network of roads and canals. “Sink down, ye mountains!” John Quincy called out. “And ye valleysârise!”

6

He portrayed the “unspeakable blessings” of Monroe's vision of a transnational network of roads and canals. “Sink down, ye mountains!” John Quincy called out. “And ye valleysârise!”

Exult and shout for joy! Rejoice! that . . . there are neither Rocky Mountains nor oases of the desert, from the rivers of the Southern [Pacific] Ocean to the shores of the Atlantic Sea; Rejoice! that . . . the waters of the Columbia mingle in union with the streams of the Delaware, the Lakes of

the St. Lawrence with the floods of the Mississippi; Rejoice! that . . . the distant have been drawn near . . . that the North American continent swarms with hearts beating as if from one bosom, of voices speaking with but one tongue, of freemen constituting one confederated and united republic of brethren, never to rise . . . in hostile arms . . . to fulfill the blessed prophecy of ancient times, that war shall be no more.

7

the St. Lawrence with the floods of the Mississippi; Rejoice! that . . . the distant have been drawn near . . . that the North American continent swarms with hearts beating as if from one bosom, of voices speaking with but one tongue, of freemen constituting one confederated and united republic of brethren, never to rise . . . in hostile arms . . . to fulfill the blessed prophecy of ancient times, that war shall be no more.

7

Â

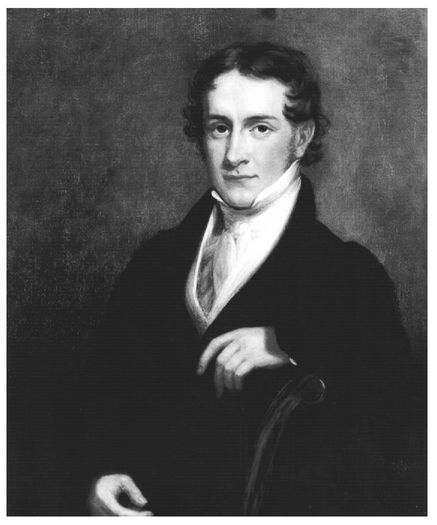

Charles Francis Adams was the youngest child of John Quincy and Louisa Catherine Adams. Like his father, he was a Harvard graduate and lawyer.

(NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

(NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

After he had delivered his eulogy, John Quincy and Louisa learned to their delight that Charles Francis's wife, Abby, had given birth to their first child, a girl they named Louisa Catherine Adams. With John II's two daughters, John Quincy and Louisa now had three granddaughters, but

they still awaited the birth of a grandson to carry the family name into the future.

they still awaited the birth of a grandson to carry the family name into the future.

By the time John Quincy and Louisa began their return to Washington for the opening of Congress in December 1831, his eloquence had resounded across the nation, with both his July 4 oration and eulogy to Monroe having been published in most American newspapers. Old political friends greeted him in New York. In Philadelphia, Albert Gallatin, his associate in Ghent, asked him to preside at the Literary Convention then in session and won his appointment to a committee drawing up plans for a National Library and Scientific Institution. By the time he reached Washington, his political enemies in Congress feared he was mounting a surreptitious campaign to recapture the presidency, and to prevent that possibility, they shunted him onto the least important committees. Instead of the Committee on Foreign Affairsâ“the line of occupation in which all my life has been passed”âhe found himself chairman of the Committee on Manufactures, “for which I feel myself not to be well qualified. I know not even enough of it to form an estimate of its difficulties.”

8

8

Although any member of the House could introduce a bill relating to anything he chose, by tradition, members limited the bills they proposed to matters within the purview of their own committees. To escape what he considered a procedural straitjacket, John Quincy decided to flaunt House tradition and use the right of every committee chairman to read citizen petitions on the House floorâregardless of their content.

On his first day in Congress, therefore, he hurled his first thunderbolt on the floor of the House, shocking both sides of the aisle with not one but fifteen petitions from Pennsylvania Quakers “praying for the abolition of slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia.” Under rules adopted by the First Congress in 1790, the House had agreed to remain silent on the question of abolitionâlargely because of South Carolina's threat to walk out at the mention of abolition or slavery. The Capitol all but imploded under the tension of his words. “I was not more than five minutes on my feet but I was listened to with great attention, and when I sat down, it seemed to myself as if I had performed an achievement.”

9

9

He had indeed performed an achievement. Although most of the House rose as one to roar its disapproval, former President John Quincy Adams had burst open the doors of Congress to abolitionist voices for the first time in decadesâvoices that other congressmen had routinely ignored for years and would never be able to ignore again. Although Pennsylvania Quakers were not his constituents, he had proclaimed himself a representative of the whole nation, and the whole nation now took him at his word, inundating him with petitions they knew their own representatives would never accept.

It was not a good time to be a proponent of abolition in America, however. Only months before, a black preacher, Nat Turner, had led an insurrection in Virginia, killing fifty-seven white people, including eighteen women and twenty-four children. Only swift retaliation by U.S. marines prevented the insurrection from spreading into North Carolina. Although one hundred blacks had been killed and twenty were later executed, the specter of future black uprisings terrified southernersâand many northernersâand southern states were tightening their slave codes to curb black mobility. Some required blacks to carry special passes for travel; others banned all travel by blacks except to church meetings. Ten states were considering or had proposed changes in their state constitutions to ban voluntary emancipation of slaves by slaveholders.

Other books

Lost In Time: A Fallen Novel by Palmer, Christie

Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life by Ruth Franklin

New World, New Love by Rosalind Laker

Mortal Kombat: The Movie (Digest Version) by Martin Delrio

His Every Touch [The Complete Series] by Lovelace, Harriet

Rage by Matthew Costello

The Two of Swords: Part 8 by K. J. Parker

The Nice Old Man and the Pretty Girl by Italo Svevo

Grilling the Subject by Daryl Wood Gerber

Chains of Revenge by Keziah Hill