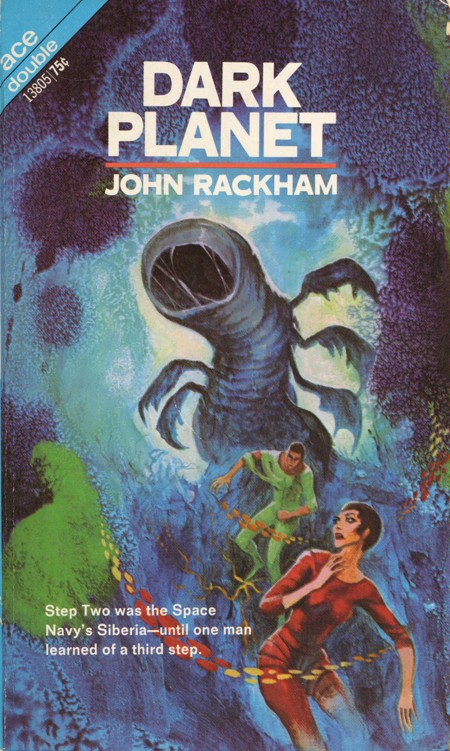

John Racham

Authors: Dark Planet

Stephen

Query had been condemned to serve out his space enlistment on Step Two, the unknown

mudball

way station. Query had been made a mere

technician there at the enclosed domed-in base because he refused to accept automaton

status. But Query found that Step Two meant for him at least the freedom of

privacy and daydream even though one step outside the Dome without protective

clothing could mean death. Or so everyone

said

...

Until Stephen and the admiral who had ordered

him to that dark planet were thrown defenseless into the muddy misty world

beyond the Dome. There could be no hope of rescue, for Step Two's officers had

concealed the crash of the admiral's vessel and no one at the base even knew

they were

lost

.

They wandered hopeless, starving and

thirsty,

knowing there was no hope—and then, there was a

noise, there were those strange colors, there was something emerging from the

dark planet beyond all conception....

Turn

this book over for second complete novel

JOHN

RACKHAM has also written:

FLOWER

OF DORADIL THE DOUBLE INVADERS ALIEN SEA

THE

PROXIMA PROJECT IPOMOEA

TREASURE

OF TAU CETI THE ANYTHING TREE BEYOND CAPELLA

DARK

PLANET

JOHN RACKHAM

ACE BOOKS

A

Division of Charter Communications Inc.

1120

Avenue of the Americas New York, N. Y. 10036

dark planet

Copyright

©, 1971, by John Rackham All Rights Reserved.

Cover art by Jack

Gaughan

.

the

herod

men

Copyright

©, 1971,

by Ace Books

Printed

in U.S.A.

H

e

stood up to his knees

in

hot mud, the wet weight of it pressing the inert plastic of his suit warmly

against his legs. Inside the suit he was a trifle more than comfortably warm,

aware of beads of sweat that formed and trickled and stung his eyes. The

lung-pack on his back labored ceaselessly to keep that level despite the close

to boiling, steamy air outside. And that air wasn't just hot and humid, it was

alive: a seething soup of microorganisms that were perpetually hungry. The

planet surface slow-boiled constantly at the bottom of a hundred-mile blanket

of shimmering blue green, voracious air that had its own furtive glow, giving a

visibility of something under ten yards, and even that was uncertain as to edge

and color. And Stephen Query liked it, felt happy in it, as he was now.

He

knew himself to be odd and was, therefore, sane. Either a man gets to the age

of maturity believing everyone else is crazy but him, in which case he is

insane, or he realizes that it's everybody else who is normal and he's the odd

one, and he stays sane.

But alone.

Query liked to be

alone. Here, if he forgot the thin thread of plastic line that was his clue

back to the Dome, he could be alone as never before.

Alone in

a sea of mud with shimmer green walls and ceiling and the silent yet urgent

surge of alien jungle all about him.

Alone to think,

not so much about this wild environment, but about himself.

There

was enough room in his mind to feel mildly grateful for the

"bending" of Dome regulations that allowed him this escape; to recall

the words of Sergeant

Keast

: "Don't see why the

hell not, Query, on your own time! It

don't

cost

anything, and you sure as hell aren't going to run off, out there.

Where to, huh?"

And "run off" was a valid

5

point

,

for service here, on this nameless planet, at this base called, simply, Step

Two, was a form of punishment. So Query had room to feel just that small twinge

of gratitude. But for everything else to do with Space Service and what it

stood for he felt no gratitude whatever. He rejected it with the solid and

total stubbornness with which he had rejected each and every other form of

regimentation that came with being human. And that itself was a problem he

needed to think about, to reach some kind of decision on.

But

thinking, for Query, was more a process of letting his mind run where it wanted

to and following after it with interest to see what it turned up, and then to

wonder at it. Such as now, in the middle of seething life that he could feel

on all sides though it was utterly silent. No birds sang; no insects buzzed;

nothing splashed the mud with running feet. But he called back his mind from

that and brought it to the question.

To be, or not.

He

knew Hamlet's speech, admired the sonorous phrases, but his problem came to

simpler terms and in older language still. "

Humanus

sum,

et

nihil

humanum

a me

alienum

puto

." I am human, and therefore nothing human is

alien to me. But he felt alien to it, inescapably. So what to do? The prospect

of yielding, allowing

himself

to be slotted into the

structure of society just like everyone else, was terrifying. It had the feel

of living death. On the other hand, was the life he had led so far so very

wonderful? Was it worth it just for the sake of integrity? Or to refine it

right down to the basics "Who

am I

, that I can

expect everybody else to move over to make room for me?"

That

fascinating but unanswerable question went

aglim-mering

as the smooth surface of the chocolate brown mud right in front of him grew a

bump. A ripple, and up came the pale green spike of something that grew with

visible speed, thrusting up like a spear, swelling, forming a bulb on a slim

stem. He could have reached out and touched it. It shook with urgency, strained

and swayed, and even as the fattening head lifted clear of the mud, he saw

ravenous decay attacking it, saw the sudden cluster of yellow spots which

spread fast and coalesced into a whole, so that the burgeoning head drooped and

bent back.

And swelled more.

And burst to discharge a

puff of tiny white

6

specks that floated on the mud for a breath

and were

gone,

were all swallowed up like their

parent.

There

was significance here. He pondered on it. Life was that fast in this hothouse,

but the essence was the same anywhere. Fight and die. Eat and be eaten. Emerge

for a brief moment then fall back into the vast anonymity . . . that was it

Individuality was a temporary illusion in the eternity of life itself. Only the

idea itself lives on. Like Space Service itself, even. Conditions changed.

Personnel changed, officers and men came and went. Ships were built and flew,

served and fell out, or were destroyed. Everything changed except the Space

Service idea, the concept itself. "And whatever else I am," he

thought, "I am not a concept!"

Trained

caution made him squint aside at the register on his helmet wall. A little

under an hour left on the lung-pack, and it would take him half of that to get

back to the Dome, trailing back along that line. That plastic link, by itself,

was something to wonder at. Without the discovery of that virtually

indestructible, totally inert molecule this base would never have been built,

would have been out of the question. And this ball of hot, sizzling mud, dark

and jungle grown, would never have known the impact of human curiosity. It was

just a wild planet of an insignificant sun, halfway between Sigma

Draconis

and the

Alkaid

cluster

in the Great Bear.

But

then Query rethought it. The plastic had made the base possible, true, but it

had been one man's decision that had brought it into reality. And that man

symbolized for Query everything he detested about society in general and the

Space Service in particular. Gareth Evans . . . even the sound of the archaic

given name was somehow typical of the man's impossible arrogance.

Old Gravel Guts Evans, general officer commanding the whole Space

Service in its glorious hour of emergency.

Glorious?

Query knew very little of what the Service had been like in peaceful times.

Like many another, he had been ruthlessly snatched from civilian anonymity and

drilled into some skill he could handle, in his case the repair and maintenance

of instruments to do with ships and drives and flight . . . and that was it.

And the Service, under the unexpected impact of the full-blown Settlers' Revolt

in the

Alkaid

cluster

,

was a curious hodgepodge. A general officer commanding who called himself an

admiral . . . technicians . . . sergeants . . . regulations that came so fast

and changed so often that no one man could keep them all in mind. A

mess,

and all to restrain a group of people who wanted to

run their own affairs without interference from Earth. An old and stupid story,

repeated in the historical record a thousand times.

Glorious?

Query

loathed it with all his being, but he had learned the hard way to at least make

the appearance of conforming. And the job had called for very little of his

intelligence. So, as so often before, he had carefully wrapped the cloak of

camouflage about himself. Until chance had ripped it wide open. Until an

inspecting lieutenant had said, offhandedly, "You have those modules

upside down,

Instrumentman

. Correct it."

"But that's correct as

per diagram, sir!"

As simple as that.

And perversely, for Query had drawn a line, as he did occasionally,

against being screwed down out of sight He was right, the lieutenant was wrong,

and he stuck stubbornly to that. Experimental test and proof would have been

simple, but that was no longer the point at issue. Minor insubordination blew

itself up into a full-scale court-martial, in itself an index of the general

morale of the time, for the rebel Settlers were having things largely their

own way then. There was also the awful fact about courts-martial in the

military mind: you must be guilty of

something,

or

it would never have got that far!

And

then chance again. It just so happened that old Gravel Guts himself was on Moon

Base at the time and decided to sit in. And though the hard-nosed court could

find nothing specific, it was he who biased the whole outcome. He, who could

think only in terms of discipline, tradition and the rule book, brought his

influence to bear. The upshot was that Query had been shipped out from his quiet

anonymity among the instrument repair section of Moon Base, and dropped here,

on this mud ball.

The forgotten men, each and every one of

them with cause to remember Evans . . . and not in their prayers.

His

job was as it had always been, to check out, overhaul, calibrate and test,

repair and/or replace all those instruments that enable

8

ships to fly; a steady, delicate, but

noninspiring

job, no matter where it was done.

Except

that here, Step

Two

, was

a

punishment in itself for the ordinary trooper. Moon Base and all the

other bases like it weren't exactly pleasure camps, but they did have

amenities.

Video, canteen, recreation spaces . . . and women.

There was also some kind of hospital-convalescence facility for the repair of

men as well as machines. And authority had learned, the hard way, that men need

women and vice versa, so the hospitals were staffed accordingly.

But not here.

Sick men didn't stop off here, only partly

disabled ships and those in need of stores, fuel and supplies. And the staff

didn't merit kinder consideration. They weren't permanent but serving sentences

of greater or lesser duration, and that was all they thought about

When

do I get away?

There was

a

kind of black psychology about it in that it made men behave, keep

their noses clean and their eyes fixed on the goal of eventual return to

civilization.

Of

them all, Query was the only one who liked it, who had come to appreciate the

alien quality of the place as having something akin to his own nature. Not that

it detracted anything from his detestation for Admiral Evans. In his mind,

that old man served as focus for his more general detestation of the whole of

humanity. For the war itself he felt nothing at all. It was just one more

example of society eating out its own guts.

Query

flicked another glance at his register.

Ten more minutes.

He dragged his mind away from futile thoughts about Evans. The old fool thought

he had meted out punishment, whereas, in fact, he had done Query

a

service. Never in all his life

had he

imagined

such a place as this.

A whole world hidden and secret, with a

dark and wild beauty all its own.

Tangled creeper and

stem and root all writhing to survive.

And those immense blue black

columns that stood straight up into the unknown mist above.

Trees

of some kind.

Enormous and inscrutable.

Did

they have leaves and fruit, he wondered? What was it all for? Could there

properly be

a

purpose in all this life, if there was no

consciousness to understand it? Sometimes he had the acute sense that this dark

underworld was as much aware of him as he was of it . . . and that feeling came

very strongly now, of something out there on the other side of his helmet

transparency, watching him.

And

he saw it. In that instant he froze dead still.

Something—just

there, beyond that nearest great bole—staring at him.

Pale,

immobile, but with eyes that had caught a glint of light for just a moment.

Eyes.

A head, now, as

he

concentrated

on it.

He felt no fear at all, just intense curiosity. What was it? He

separated shape from shadow, slowly.

A head, with the dark

shadow of short hair, flat and moist in curls.

Nostrils

and a chin, a mouth.

Neck and shoulder and an arm.

All pale, a kind of

greeny

cream, which could be an

effect of the light. But

humanoidl

He

held his breath in amazement, astonishment and delight all at once.

Definitely a human shape as far as he could see in the deceptive light.

Cowering behind a tree and watching him.

Possibly as amazed

and astonished as he was.

Query itched in his mind with a vast wonder.

Not the wonder of how anything humanlike came to be here at all. There the

creature was, and that was enough.

But

what

kind

of creature was it. Human in shape; it moved cautiously now, an arm,

elbow and hand coming to rest on the tree bole . . . definitely a humanoid. But

what did it think

,

if anything? What dreams and hopes

and fears?

What

must

you

think

of

me,

in

this

crazy

suit?

he

thought.

I

wish

you

could

talk,

and

I

could

understand.

A

rivulet of sweat ran into his eyes, blinding him for a moment, and when he was

free of tears again—it was gone. Another mind would have sent the idea packing

as illusion, but Query never even thought about it.

I

'll

be

back,

he thought, saying it in his mind.

I

'll

be back.

We

have

to

meet

again,

somehow.

Tell

your

friends.

And

he flicked another glance at his register and swore. He had undercut his time.

Now he would have to scramble faster than ever before to get back there before

his lung-pack quit on him. It wasn't easy to hurry in this murk. He took the

line and reeled it over his left hand and elbow as he followed it back through

mud and rioting creeper, around huge boles, crashing through thick shrubs, and

in one spot stuck for several minutes while he argued with a snakelike root

that had intimately entwined itself around the line. Precious minutes went

away. He floundered on, sweat streaming into his eyes and his incoming air

growing hot and foul as the lung-pack labored through its last few resources.

The filters would be solid now, the power pack feeble. He felt the liquid of

his own sweat filling up inside the suit as he shambled on, whooping for

breath, half-blind with sweat. And then, suddenly, the mud was less and the

ground under his feet had a crust. And there was the Dome, looming

grayly

out of the mist. He hit the air lock button and

leaned against the wall, fumbled at the snap hook on his line as the hatch

cycled open and out, staggered inside and waited while it shut again, saw the

eye-twisting blue of U.V. come on and heard the air pumps kick in. A minute

more,

and he could lever his helmet back and breathe

gustily, gratefully, and then tear at the Velcro seals of his suit and peel it

off.

"That

was close!" he muttered, shivering as the dry air sucked away the sweat

from his bare body. "Too close. Sergeant

Keast

ever got to hear, he might put the ban on." And that was a sobering

thought. He turned the suit inside out to clean itself, took his one piece,

snug fit, disposable uniform suit from the hook where he'd left it, climbed

into it, grabbed the depleted lung-pack, and then leaned on the inner switch to

set the door cycling open. This would be the worst time to be forbidden his

pleasure jaunts outside, now that he had found humanoids out there. The first

thing to come through the doorway at him was noise, above all the noise of

Sergeant

Keast's

file hard voice halfway through a

familiar indoctrination speech.

. .

assigned your work details immediately after chow-time, which is five minutes

from now and lasts thirty minutes, at which time you will fall in again here,

which is known as the assembly area, and

I

'll

give you the rest of the rundown at that time, to which you will pay attention,

but hear this.

I

will be the last to arrive.

I

better be.

Dismissed!"

New arrivals.

Query wasn't curious about them or anything else to do with Sergeant

Keast

. Just the sound of that voice, with its machinelike

monotonous grind, was enough to banish forever any faint imaginings he may have

had about telling anybody what he had seen out there. He went away as

inconspicuously as possible, heading for stores.

But not

furtively enough.