Joseph E. Persico (3 page)

Authors: Roosevelt's Secret War: FDR,World War II Espionage

Tags: #Nonfiction

Myron Taylor, FDR's personal representative to the Vatican, with Pope Pius XII. Taylor exposed the biggest intelligence hoax committed against the White House in World War II. (FDR Library)

FDR with Joseph Stalin at the Big Three summit in Tehran, where a plot to assassinate the President was uncovered. (FDR Library)

Russian maids prepare a room in the American quarters during FDR's meeting at Yalta with Stalin and Churchill. The Soviets had planted dozens of hidden listening devices in all the rooms. (FDR Library)

An American sailor trains a Russian sailor during Operation Hula, in which the United States secretly turned warships over to the Soviet Union as part of FDR's strategy to draw Stalin into the war against Japan. (Naval Historical Center)

Churchill's pressure on FDR to make Britain a full partner in the development of the atom bomb led to the assignment of British scientists to Los Alamos, among them Klaus Fuchs, who stole secrets about the bomb for the Soviet Union. (UPI/Bettmann Archive).

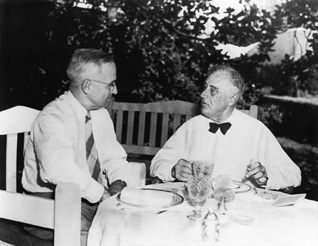

FDR with his 1944 running mate, Senator Harry S. Truman. Truman later claimed he knew nothing of the atomic bomb before becoming President, but Roosevelt may have told him of the weapon during this lunch on the White House lawn. (FDR Library)

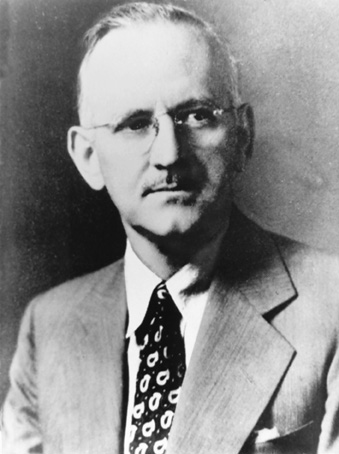

Lauchlin Currie, a close FDR aide. Was he consciously providing White House secrets to the Soviet Union, or was he merely an ingenuous dupe? (FDR Library)

Elizabeth Bentley, a former courier for the Soviet Union, who went to the FBI and then before Congress to denounce alleged spies in the Roosevelt administration. (National Archives)

FDR aboard the presidential yacht

Potomac

with his distant cousin and confidant, Margaret “Daisy” Suckley (center), with whom he shared wartime secrets. She was with him at the time of his death. (FDR Library)

Foreword

THE genesis of this book lies in my lifelong fascination with Franklin D. Roosevelt. As a boy growing up in New York State, it seemed to me that the nation was governed by a triumvirate as immutable as the heavens. Fiorello La Guardia was New York City's mayor, Thomas Dewey was the state's governor, and Roosevelt was the president. Subsequent ascendents to these offices seemed, to an immature mind, unwelcome interlopers. The brightest star in this constellation was, of course, FDR.

Most of my previous books have dealt, in whole or in part, with espionage and World War II. After a search of some six hundred Roosevelt entries in the Library of Congress, I was surprised to find that none covered specifically the President's involvement in World War II intelligence. I saw an opportunity to fuse my interests in the man, the field, and the era.

Few leaders have been better suited by nature and temperament for the anomalies of secret warfare than FDR. “You

know I am a juggler, and I never let my right hand know what my left hand does,” he once confessed. “I may be entirely inconsistent, and furthermore I am perfectly willing to mislead and tell untruths if it will help me win the war.” His style of leadership bears out this admission. FDR compartmentalized information, misled associates, manipulated people, conducted intrigues, used private lines of communication, scattered responsibility, duplicated assignments, provoked rivalries, held all the cards while showing few, and left few fingerprints. His behavior, which fascinated, puzzled, amazed, dismayed, and occasionally repelled people, parallels many of the qualities of an espionage chief.

FDR's talent for intrigue was merely another weapon in the Rooseveltian arsenal, along with vision, courage, charm, and unquenchable spirit, that he employed toward laudable endsâcombating the Depression, seeking social justice, and winning the war. As for the last objective, his benign duplicity was best captured by his son James. “I

had a conversation with father,” the young Marine officer writes, “in which I discussed the dishonesty of his stand on war.” “Jimmy,” FDR explained, “I knew we were going to war. . . . But I couldn't come out and say a war was coming, because the people would have panicked and turned from me. . . . If I don't say I hate war, then people are going to think I don't hate war. If I say we're going to get into this war, people will think I want us in it. If I don't say I won't send our sons to fight on foreign battlefields, then people will think I want to send them. . . . I couldn't take every congressman into my confidence because he'd have run off the Hill hollering that FDR is a war monger. . . . So you play the game the way it has been played over the years, and you play to win.”

Still, the President took almost childish delight in subterfuge for its own sake. Roosevelt loved being told secrets and retailing gossip. He was accused by enemies and friends alike of being devious and lacking in candor, and justly so. He dangled people like puppets on the string of his whims. He would fool those who thought they could predict his moves by changing course. His early New Deal ally Rexford Tugwell observed, “He

deliberately concealed the processes of his mind.” His vice president Henry Wallace concluded that the only certainty in dealing with the man was the uncertainty of “what went on inside FDR's head.” As one scholar put it, “Nothing

would have pleased him more than to observe historians arguing passionately about what constituted the âreal Roosevelt.'” His inscrutable nature found full play when America went to war. The man with the instincts of a spymaster now had a war in which to indulge his attraction to the clandestine.

Wars are won by superior might wedded to military performance. Espionage is a handmaiden, not the instrument of victory. But a war's outcome is affected by the genius or ineptitude, the coups or blunders, the measures and countermeasures of secret warriors. How FDR performed on that clandestine front is the story that follows.

Albany, New YorkJuly 19, 2001

Prologue

THE President had been awake since eight-thirty this Sunday morning, December 7, 1941. He

sat in bed flipping through the thick Sunday editions of

The New York Times,

the

Herald Tribune,

the two Washington papers, even the hateful

Chicago Tribune,

snapping the pages with a rapidity that created a breeze; yet he would later be able to recall what he read with a retentiveness that daunted his aides. His valet, Navy Petty Officer Arthur Prettyman, helped FDR out of bed and into his wheelchair, a makeshift affair adapted from a kitchen chair with the legs cut off and the seat mounted onto a metal frame. Prettyman wheeled FDR into the bathroom, where the President began shaving himself with a straight razor. He

dressed casually this morning, finishing his attire with a baggy sweater that belonged to his son Jimmy. He was looking forward to a day of rest. The night before Mrs. Roosevelt had arranged dinner for thirty-four guests, an eclectic list including relatives, friends, White House aides, middle-ranking government officials, and military officers. To

one guest, the ensemble suggested an exercise in social catch-up. The

President had excused himself early and left before the musicale led by the violinist Arthur LeBlanc, not precisely FDR's cup of tea. One guest, Bertie Hamlin, whom FDR had known since his youth, thought the President “looked

very worn. . . . He had an unusually stern expression.”

His mood was explained by intercepted and decoded Japanese messages reaching his desk in recent weeks which suggested a Japan bent on war. Back in his room the President took a pad and began drafting in his bold hand an appeal to Emperor Hirohito to join him in a statesman-to-statesman effort to stave off disaster. But within a half hour of dispatching this olive branch to the emperor, FDR's hopes were dampened. A young naval aide, Lieutenant Lester R. Schulz, just two days on the job, brought to the President the latest decrypted message from Tokyo, instructions to the Japanese ambassador in Washington spelling out what the President regarded as intolerable demands. It was near midnight before Prettyman

lifted a drained FDR into bed.

The next morning, the world looked brighter as the President breakfasted on his customary orange juice, coffee, toast, soft-boiled eggs, and bacon. The sun rose in a clear sky bathing the East Wing of the White House in pale gold light. The

weather, for December, was glorious, cool, heading toward a high of forty-three degrees. Golfers were getting ready to tee off at Washington's Burning Tree course, among them CBS's broadcast star, thirty-three-year-old Edward R. Murrow, just back from London. The

President had invited Murrow for supper that evening to learn firsthand how the British were bearing up under the Blitz and Hitler's string of unbroken conquests. “Wild

Bill” Donovan, just six months into his job as Roosevelt's spy chief, veiled by the opaque title Coordinator of Information, had gotten away from the capital for a late-season football game between the Brooklyn Dodgers and the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds.

As

Prettyman removed the debris of the President's breakfast, FDR called for his doctor. His

chronic sinusitis was acting up, but otherwise he appeared to have shed the cares of the night before.

Admiral Ross McIntire left his dispensary on the first floor and strode through the unaccustomed Sunday-morning stillness of the White House, his heels echoing hollowly up the stairway. Outside, the capital's streets were deserted and traffic sparse. Washington

was a sleepy, middle-class city populated by middle-class government workers who abandoned downtown on the weekend. The

silence was broken only by the peal of the bells of St. John's Church across Pennsylvania Avenue on Lafayette Square, summoning worshippers to morning services. As McIntire entered FDR's study, the President reflexively rolled back his large, handsome head, and the doctor administered nose drops. FDR blinked, sat up, and launched into one of his anecdote-strewn monologues. Roosevelt and McIntire had first met aboard a cruiser when FDR was assistant secretary of the Navy and the doctor a young medical officer. Roosevelt remembered the affable MD thereafter and brought McIntire into the White House, where he began his heady ascent to his present rank. The President

and his doctor swapped stories for almost two hours before FDR prepared himself for his only official appointment that Sunday, a visit by the Chinese ambassador, Hu Shih. Then he could do what he really wanted, which was to work on his stamp collection, his passion since he was eight years old.

At 12:30

P.M

., the ambassador was ushered into the White House. In tune with the leisurely day he had in mind, the President chose to see Hu Shih in his upstairs study rather than in the more formal Oval Office below, though both rooms reflected FDR's casual disarray. Stacks of books, piles of yellowed papers tied with string carpeted the floor, and FDR's ship models sailed along the tops of bookcases. Portraits

of the President's mother and wife studied each other across opposite walls. Hu Shih found himself assigned a role familiar to Roosevelt's visitors, serving as a sounding board for whatever popped into the President's mind. This day FDR wanted the ambassador to listen to what he had cabled to Hirohito the night before. He read with relish from his literary handiwork. “I got him there; that was a fine, telling phrase,” he exclaimed. “That will be fine for the record,” he added, punctuating the point with a stab of his cigarette in its ivory holder. Hu

Shih left the President's study a half hour later, having heard much and said little.

As his guest departed, FDR turned eagerly to the manila envelope sent over the day before from the State Department. His hobby had prospered mightily after he became president. Mail came into the department from all over the world, and every Saturday a messenger delivered a batch of the most interesting stamps to him. He

asked his valet to bring him the tools of his avocationâhis album, magnifying glass, scissors, packet of stickers, and the collector's bible,

Scott's Stamp Catalogue.

Harry Hopkins, FDR's gaunt constant confidant, padded down the hall from the bedroom he occupied next to the Lincoln study. Another large list of guests had been invited for lunch this Sunday, though, as Eleanor later recalled, “I

was disappointed but not surprised when Franklin sent word a short time before lunch that he did not see how he could join us. . . . The fact that he carried so many secrets in his head made it necessary for him to watch everything he said, which in itself was exhausting.” Instead, the President had chosen to have lunch alone with Hopkins. They ate off trays, Roosevelt's set on a removable rack affixed to his wheelchair. FDR stabbed desultorily at his food. The White House chef, Henrietta Nesbitt, was notorious for dull menus. Eleanor had met her through Hyde Park politics and, for some unfathomed reason, had decided the woman would make a good housekeeper. FDR's son Jimmy found Mrs. Nesbitt “the worst cook I ever encountered.”

While the President munched on an apple and flipped through his album, Hopkins stretched out on a couch. Their conversation was light, bantering, with serious concerns set aside this day. At 1:47

P.M

., the phone rang. FDR

picked it up. The White House operator apologized for intruding, but she had Navy secretary Frank Knox on the line, and he insisted on speaking to the President.

“Put him on,” FDR said. “Hello, Frank.” His voice took on its habitual gaiety.

Knox's voice was choked. “Mr.

President,” he said, “it looks as if the Japanese have attacked Pearl Harbor!”

“No!” Roosevelt gasped.

Knox

said that he had no further details, but would keep the President advised. Hopkins, learning what had happened, was incredulous. There

must be some mistake, he said. Japan would not attack Honolulu. FDR quickly regained his composure. His wife had long ago observed, “His

reaction to any great event was always to be calm. If it was something that was bad, he just became almost like an iceberg, and there was never the slightest emotion that was allowed to show.” To Hopkins's doubts that the Japanese would make such an attack, the President

responded that this was just the kind of thing they would do, talk peace while plotting war.

The United States had fallen victim to the most stunning failure of intelligence in the country's history, likely in the entire history of warfare. What happened that tranquil Sunday had been preceded by and would be followed by fluctuating triumphs and failures in something relatively new to Franklin Roosevelt, the sub rosa battlegrounds of espionage. The story began in 1938.