Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (3 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

Plato’s thoughts on emotion and reason are most explicitly laid out in the

Republic

, his essay on morality and the ideal state, but also in its sequel, the

Timaeus

, where he sketches out his ideas on the physiology of the soul and makes clear reference to the parts of the body that he believed hosted it.

6

According to Plato, the human soul was animated by three main types of passions or energies: reason, emotion and the appetites. Of the three, reason was by far the noblest, whereas emotion, and even more so the appetites, were second-order passions, granted lower status. The appetites were our basic needs, such as those for food and sex, as well as greed for money and possessions. Emotion was impulsive, unguarded reactions, such as anger or disgust, but also bravery. By contrast, reason meant calm reflection, zeal, persuasion and argument. Conveniently, the tripartite soul mirrored Plato’s triune social division of the state. The lowest class, the proletariat, embodied the appetites, notably stinginess and greed. Among the warrior class the emotions dominated. The guardians, the highest class in Plato’s society, personified reason.

It was to reason that Plato granted most importance, claiming that only a rational man could be both just and moral. Basically, the passions must submit to whatever reason dictates. This tripartite idea of the mind flourished, in different permutations, almost unquestioned for about two millennia.

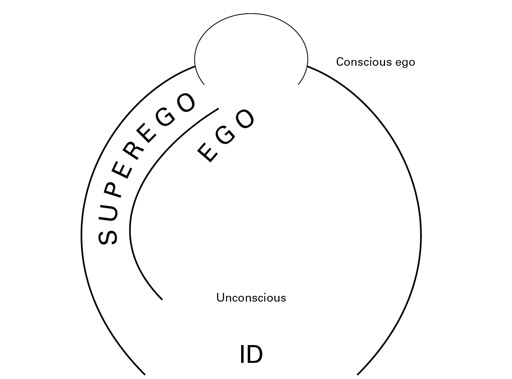

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), a Viennese physician and the father of psychoanalysis, who certainly believed in the importance of emotions, parcelled rationality off from basic instincts and acknowledged the conflict between the two. The most primitive human desires constituted what Freud called the id, Latin for ‘it’. This vague, amorphous part of the human mind encapsulated its most visceral instincts. The workings of the id are free of all logic or rationality. They are also outside our conscious perception and control. Essentially, the id is the most rudimentary mental survival mechanism, the one we share with all lower animals and that we are born with, and it has two main objectives: the attainment of pleasure and the avoidance of pain (Fig. 1).

Above the id in Freud’s hierarchy of the mind was the ego, which constituted human rationality. The ego works both consciously and unconsciously. In its conscious form, the ego is what takes care of the mind’s perception of and relationship to the outside world, through the five senses. The ego is what makes us plan ahead. Through its unconscious qualities, the ego also exerts inhibitory control on the id, repressing some of its instinctual drives.

Fig. 1 Freud’s structure of the human mind. Most of our mental processes are uncon scious, floating underneath our awareness. Only a tiny part of our thoughts and emotions is fully conscious (top of diagram). The id represents our most visceral instincts. The ego is the seat of our rationality and consciously governs our relationship to the outside world. It also unconsciously represses some of the id’s instincts. The superego represents our sense of morality, shaped by society and culture. (After a diagram in

New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis

, 1933, Lecture XXXI)

7

Lastly, at the top of the ladder, was the superego, our conscience and the repository for our sense of guilt, a moral apparatus moulded by society and culture.

Despite Freud’s initial interest in the brain – he started his career as a highly regarded neurologist – the physical location of these components of the human mind did not concern him. Even so, he remarked several times that his psychological theory of mind would one day be replaced by a physiological and chemical one. And his prediction would be confirmed.

Ideas cemented in the brain

The time-honoured severance of emotion from reason retained credibility until not long ago, partly because it found confirmation in the understanding of the anatomical and functional design of the brain.

8

Fitting with the authoritative precepts of evolutionary development, the prevailing functional maps of the brain allocated its functions according to their evolutionary history. The division of labour was thought to be roughly as follows.

The oldest parts of the brain were those ensuring the control of the most primitive and rudimentary functions. In today’s map of the brain, they are its most internal parts: in temporal terms, the brain’s beginning. The further out you moved from the core, the more sophisticated the tasks that the brain could accomplish. Deep in the meanders of the brain, sitting on top of the spinal cord, is the brainstem, a kind of automatic survival system, without which we wouldn’t even be able to breathe. The brainstem is the pillar of our physiological existence (Fig. 2). It contains structures such as the medulla, which controls breathing and heart rate, and sends and receives signals to and from vital organs. It can be thought of as the general ‘power switch’ of the brain. If something happens to the brainstem, the whole system shuts off, and that is why, for instance, an injury to the brainstem in a fall or other kinds of accident is fatal. Closer to the outside surface, but still in the core of the brain, are units whose function adds emotions to the basic survival mechanisms of the brainstem. It is within these deep structures that emotions in their rawest form are processed. Together these structures – which, roughly speaking, include tissues with extravagant, almost mythological-sounding names such as the thalamus, the hippocampus and the amygdala – are called the limbic system. ‘Limbic’ derives from the Latin

limbus

, which means border or edge, an appropriate name for this set of tissues which protrude from and cover the brainstem.

Lastly, wrapped around the limbic system and the brainstem, is the cortex (Latin for bark). The cortex is the last addition to the brain yet it is the most evolved. When the cortex first appeared, it was rather thin. Over time – evolutionary time, therefore millions of years since it first appeared – it continued to grow within the boundaries of the skull, increasing the number of neuronal cells and therefore its capacity. In mammals, over a hundred million years ago the cortex underwent remarkable growth and became what is now called the neocortex, the most sophisticated version of the cortex.

9

Covering the rest of the brain like a cap, it is made up of large, convoluted folds of tissue that make the brain appear like a wrinkled sheet.

Fig. 2 Schematic diagram of the brainstem, limbic system and neocortex

The areas where the tissue turns are called gyrii, while the intervening furrows are called sulci. Within the neocortex, the part that has undergone most of the change and that has grown in mammalian history is the most anterior part, the prefrontal cortex, or PFC, just behind your forehead and eyes.

The PFC occupies almost one third of the entire volume of the cortex. We are the only species on earth with a prefrontal cortex as big and sophisticated relative to body mass. If we compare the development of the brain to the construction of a house, the prefrontal cortex is its highest storey, the brain’s lofty attic. It helps us plan ahead and choose a preferred path of action. It also aids our short-term memory. If someone tells us their phone number, it is via the PFC that we keep it in our mind before we save it on our phone. In general, the PFC also controls our attention. It helps us focus and concentrate, and not drift away from a task.

Importantly, the PFC reaches its full form late in an individual’s growth to maturity. It is not wholly developed until after adolescence, in the early or mid twenties, which is why children and adolescents are not fully equipped for difficult decision-making and are more prone to take risks.

All these regions of the brain do not simply lie on top of one another. They are joined, producing an integrated, harmonious appearance and a functional form. The more rational part emerged from the existing impulsive core and, as a result, the two are densely and strategically connected to communicate with each other and regulate emotion.

• • •

So, for many centuries, rationality and emotionality were considered two opposing properties of the brain, operating as competing territories. They were like two substances that repelled each other and never mixed, rather like oil and water. The rational brain helps us analyse facts and assess external events, while the emotional brain tells us about our internal states.

10

During the past two decades this rough division of labour in the brain has been challenged. The brain’s geographical boundaries as regards the accomplishment of rational tasks and emotion have blurred. The prefrontal part of the brain still holds the reins of rationality, but it also contributes to emotion.

This crucial and fascinating reversal in the understanding of the role of emotion has been underpinned by experimental work, particularly that of neuroscientist Antonio Damasio. Before we consider this, I need to tell you a story.

Skin reactions

It is common practice in biology and medicine to understand the ordinary mechanism of the function of a tissue, an organ or even a gene by simply observing what happens when that function is removed or meddled with. In the history of neuroscience, patients who suffered brain injuries or underwent brain surgery have provided insightful, fascinating stories that illustrate how lesions in specific cerebral regions may result in marked alterations in behaviour. Some are particularly telling and memorable.

By far the most famous and most often recounted such story concerns Phineas Gage, a 25-year-old American who in the mid nineteenth century worked as a railway construction foreman and suffered an unfortunate and unusual accident in the course of his duties. Since new rail lines needed to be laid across the state of Vermont, it was essential to flatten the uneven ground and Gage was responsible for carrying out controlled explosions. The procedure was relatively straightforward: Gage had to first drill holes in the ground, fill them with dynamite, insert a fuse and lastly push a tamping iron down the holes after the explosive powder had been covered with sand. On 13 September 1848, because someone called him and he briefly turned round, something in the protocol went wrong. Gage started to tamp before one of his assistants had applied the sand. This was a grave mistake, because, without the sand, the explosion spreads away from the rock. The result was that the tamping iron, over a metre long and three centimetres thick, blew out and went right through his head, exiting from his left cheek, before it rocketed into the sky and fell to the ground several yards away, leaving everyone present astounded.

11

It’s hard to believe, but Gage survived. Remarkably, after momentarily losing consciousness, he regained it immediately after the accident. And, after a few weeks of convalescence, he recovered fully. His language and intellectual capabilities were entirely unaffected. He could walk, run, talk and interact with people and even go back to work. Over time, however, everyone noticed a few changes in his personality.

Before the tamping iron penetrated his skull and brain, he was unanimously regarded as a considerate, loyal and friendly man by his peers. At work he was praised as one of the best and most efficient workers, the company’s favourite. However, after the accident and as early as his convalescence, he had bursts of anger, became impertinent and impulsive and lost his capacity to judge the social acceptability of certain of his ways of behaving. He became unreliable, offensive and irresponsible towards others.

12

Eventually Gage was left isolated by his friends and acquaintances. He lost his job and never found another. Having descended into a desolate existence, he died a dozen years later.

This tragic story is scientifically compelling in that it demonstrates the links between brain damage and behaviour, in particular social and moral behaviour.

13

Gage’s case showed that compromising a fraction of the brain can have serious and noticeable consequences on a man’s personality. His skull and the infamous tamping iron remained on display at the Warren Anatomical Museum at Harvard University and, remarkably, for a long time they did not receive the attention they deserved. In the mid 1990s Antonio Damasio and his colleagues at the University of Iowa College of Medicine decided to examine the skull to reconstruct the accident and closely map the brain areas where the lesion occurred. They established that the tamping iron had specifically damaged the ventromedial part of the prefrontal cortex. This was an important clue. Damasio had met other patients with similar lesions and comparable behaviour. So he set about investigating them.