Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love (36 page)

Read Joy, Guilt, Anger, Love Online

Authors: Giovanni Frazzetto

Tags: #Medical, #Neurology, #Psychology, #Emotions, #Science, #Life Sciences, #Neuroscience

The union of two people requires they courageously abandon the safety of their own solitary spaces, to include, make space for and partake of a different – sometimes entirely different – world. It demands that the individuals involved be able to understand and overcome their differences and appreciate the way the other thinks, and imagines life. This is an interesting but entirely insecure journey. Online dating sites that employ scientific information claim that they let users find their ultimate, long-lasting match because a match based on molecular information is more likely to be successful. But even if the psychological compatibility discovered through these methods has scientific rigour, the idea that a long-lasting match may be grounded on the information of a few hormones goes against a basic requirement for the success of a love relationship: that the two individuals

learn

how to love each other and commit to spending a life together, despite their differences. Traits are not immutable. What these dating services are able to offer is the starting basis for a rapport, the appropriate chemistry through which the union has a chance to begin. Sometimes it will last, sometimes not. Because of our hectic life, our increased mobility and the widespread dissolution of traditional modes of courting and socialization in general, online-dating shortcuts to a romantic match may sound more practical, appealing and effective than conventional methods. However, the likelihood of success is not guaranteed to be any higher for a relationship started via a science-based dating platform than for one stemming from a random encounter. Personally, I hope that traditional encounters won’t become extinct.

Coda

It is an interesting circumstance that, in search of inspiration and comfort before a date, I found myself absorbed in Plato’s writings, rather than the details of a laboratory experiment. The allegory of the charioteer and the two discordant winged horses echoed the madness of love and the struggle between controlling or yielding to it. But what the allegory ultimately symbolizes is a question which is at the core of this book and the essence of love: how emotion meddles with reason.

Can we employ reason in love, when love is complex, acknowledges no laws, is evanescent and by definition a form of insanity? Can we, and should we, resort to science for matters of the heart?

As an intrinsic and tangible part of our lives and the natural world, love deserves investigation. We are entitled to understand its attributes, build up experience about it and make sense of its unpredictable outcomes the best way we can. Nothing should stop our curiosity to learn about love. Molecules, and scientific empiricism in general, add to the heap of knowledge that is already at our disposal to make sense of it.

However, the amount of scientific data on love is modest compared with what has been said and produced for millennia on the subject of love in the absence of a clear scientific explanation. Because of the dearth of reliable and unequivocal data, I believe that another kind of empiricism, one based on first-hand experience or trial and error, should remain a source as good as, if not more valuable than, any information we may gather from close inspection of a brain in an fMRI scanner.

Certain aspects of love are simply not amenable to scientific investigation. Most studies seeking to dissect romantic love have been limited to mapping its neural anatomy and describing some of its molecular components. Such findings are illustrative of the power of science to reveal the invisible wonder of a phenomenon, but are of little use when we encounter love in our lives. A philosophical or literary work such as a Platonic dialogue or a Shakespearean sonnet can teach us about love’s blindness better than can a brain scan or a hormonal test, and will prove more instructive to those in search of tips or desirous to understand the course and excitement of courtship and love. They resonate more loudly and lastingly with anyone looking for experiences with which to

identify

. For instance, what Stendhal called ‘crystallization’ is a phenomenon we can all grasp without mapping it on the brain. Knowing that gazing at the picture of a beloved dampens the flow of oxygen in brain areas responsible for formulating judgements on the person we are looking at can do little to save us from misattributing qualities to the creature in question.

An ambition arising from the neural and molecular investigations on love has been that of understanding its chemistry in order to exploit it, such as in the case of science-based online dating websites. In general, the employment of science in the search for a sister soul is an attempt to replace the randomness of love with some kind of certainty. It signifies a belief that we can first rigorously choose who would be the best person to fall in love with, and then fall in love with them. But this would be to turn love on its head and dispel its enchantment. In addition, science seems to focus on what it takes to start a love relationship, on how to ignite sparkling romance.

The successful rapprochement of two human beings who aspire to share love depends on an intricate balance of factors that are hard to pin down and orchestrate. On one hand, we have the mark left by our parents, their genetic contribution and their style of upbringing. On the other, we have our own genes and a few unforgiving neurotransmitters that circulate in our bodies. Add the unending and unpredictable everyday experience that moulds our neurons and shuffles our emotions. Then comes social structure and our place in it, the matching of cultural and educational backgrounds as well as personal or recreational interests, let alone political views – I am sure I have left out other important subtle factors here.

I know . . . The totality of these elements makes the alignment of two life-trajectories appear so rare it would make a solar eclipse mundane.

It may be a commonplace observation, but I have come to believe that love simply occurs when two individuals happen to feel a mutual attraction, enjoy each other’s company, are keen to embark on adventures together, and are also on the same page and willing to try out the match.

Sadly, it is often the case that when the other person is open to a relationship, we are fearful or, the other way round, when we are ready, they are not – again those patterns . . . And, if someone’s heart is not open, there is little we can do to unlock it. There are no flowers, poems or charming surprises that may persuade them to yield. Our persistent attention can definitely help, but if they regard themselves as unworthy of love, even if we tell them they are, they won’t believe it until they discover it themselves. This normally has nothing to do with our talents. We may have several respectable qualities on offer, but until our objects of desire are at ease with their own, ours won’t make the right impression. They may just prove intimidating. Equally, before going on the prowl, it definitely helps to check first how much we love and consider ourselves worthy of appreciation.

Love is joy’s brother. To feel love, it helps to be joyful. And here I mean the joy of a smile as well as the awareness of who one is that will at least give others a reasonably clear picture of the person who desires them. I find it helps to be tenaciously passionate about what one likes and what one detests, enthral an object of desire with enthusiasm and basically show them that being in one’s company is the best thing that could ever happen to them. It also helps, through behaviour and actions, to show and reassure the other how sincere we and our feelings are.

Even though the picture may look dim and far from simple, I am not trying to discourage anyone from pursuing or understanding love. I personally prefer to let myself be captured by love in all its uncertainties and forms of expansiveness. We live in a society that incites us to achieve and succeed rather than attach and love. As a consequence, the world seems to reward solitude rather than companionship, and to put into jeopardy the kind of self-effacing attitude and commitment needed to create a trusting relationship. Fear of loving is widespread. Fundamentally, fear of love is fear of risk. We are scared to take chances, make mistakes, be hurt or waste an opportunity. We prefer safety and expect to have guarantees. The use of science to prescribe romance, emotional compatibility and loving relationships that won’t fail reinforces our fears and our desire for certainties. It also propagates the idea that we can predict love outcomes. But too much caution and calculation are the wrong approach to love. They won’t lead us far.

We would do a tremendous disservice to our own and everyone else’s happiness if we saw love as something that has its best destination already set.

In my opinion, what counts most in love is the art of the journey, the fragile enterprise of building trust, day after day. Love is knowledge. It means to create spaces for mutual respect and for the unexpected. It means to evolve both individually and as a pair, with gratitude and responsibility.

Love should also be adventurous. In my experience, it’s preferable to take a few bumps here and there rather than have a closed heart. For when love is ripe – even between two people who didn’t regard themselves as lovers at first – it doesn’t take no for an answer. It falls like a sudden rain when you are under no roof and carrying no umbrella, imposing itself between two beings with the greatest power of persuasion and saying: you don’t need a shelter, I am the shelter.

Epilogue

No theory of life seemed to him to be of any importance compared with life itself

OSCAR WILDE

I

began by questioning whether knowledge about the brain can be of help in understanding ourselves and our emotions in the twenty-first century and I hope that, throughout the pages of this book, I was able to exemplify when neuroscience did shed light on my path, but also the instances where neuroscience just wasn’t enough.

When I experience or examine an emotional incident along my trajectory as a man, a friend, a lover, a son or a colleague, the first reservoir of knowledge I consult for explanations and meaning is hardly ever neuroscience. Or, I should say, it’s not exclusively neuroscience. I search for and side with the explanation that is most apt for an understanding of what I am feeling, regardless of whether the explanation comes from a scientific experiment, a work of art, a poem, a philosophical theory or even other sources, including my own past experience with a particular emotion.

By no means am I trying to suggest here that neuroscience is inadequate in addressing emotions. In the relatively recent past, the science of the brain has provided us with fresh accounts of how we emote, some of which may well resonate with us. It’s hard not to be fascinated by Damasio’s theory of emotions and somatic marker hypothesis. The fact that emotion guides reasoning overturns centuries of mistaken assumptions about our rationality and the way we face choices. That our emotional experience writes itself somehow in our bodies, in our neurons, to guide our instinct and intuition, and that we may have discovered where in the brain this inscription occurs is an irresistible notion. Equally, the discovery of the plasticity of the brain is of great relevance if we think of its meaning and importance in, for instance, overriding unwanted patterns of fear, or even honing our approach to love. There is endless wonder in the images of neuroscience. Yet they do not cover the entire breadth of an emotion.

When I describe an emotion in scientific terms, I always wonder: is what I am saying correct? Am I doing my emotions justice? Am I doing science justice, for that matter? When listing brain regions, nerves or competing chemical actions, I do marvel at how something as complex and at the same time ephemeral as emotions can be confidently translated into discrete detailed models, but I always bear in mind that there is a distance between what such details describe and what I feel.

This brings me to another reflection. Most of what we first learn about life, the nature of human beings and their emotions emerges from life itself, from our personal vicissitudes. My own subjective account of emotions is free of the constraints of science. There are no borders within which to fall, no molecular nomenclature to respect. It is simply what I feel: a rich, intimate speech that the language of science cannot and will not – well, at least not in my lifetime, I believe – replace.

Such direct and immediate appreciation of emotions is a plane of knowledge at the heart of everyone’s existence. It is a speech that belongs to us alone. The objective, third-person, detailed accounts of what we suppose is taking place in the brain as we speak, cry, laugh, feel guilty, miss or love somebody can be valuable, fascinating additions, but are sometimes only minor footnotes.

So, knowledge of the detailed neural subtext of brain tissues, neurons, stretches of DNA and molecular fluctuations does not always contribute to composing the daily script of our emotional lives. To fill those gaps and cover the distance that separates us from understanding our emotions, we are entitled to take all kinds of shortcuts. Many different roads lead us in the direction of

Know Thyself

.

As citizens of life and consumers of knowledge in a time when science dominates the public discourse, we can learn how to skilfully and harmoniously integrate science teachings, art, poetry, philosophy as well as our own observations as human beings. Throughout my life, I simply haven’t been able to disjoin these various ways of looking at the world – they have belonged to the same library shelf. And that’s because no view is on its own sufficient or satisfactory. There is absolutely no reason to live by only one set of ideas and not be curious about or open to others. All approaches will always leave questions unanswered. There will always be more to discover.

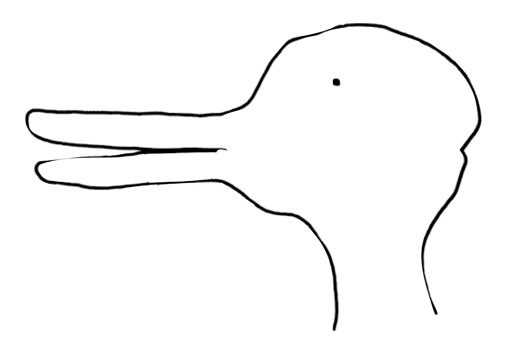

Take a look at the picture below and ask yourself what you see.

1