Julia Child Rules (7 page)

Authors: Karen Karbo

What is it about beef bourguignon? Really, it’s just beef stew braised in red wine, an ancient peasant dish from Burgundy that married up. Auguste Escoffier, the father of modern French haute cuisine, described the basic recipe followed by most of us; Julia modified it; Judith Jones, Julia’s editor at Knopf, mastered it, as did my mother, as did Julie Powell, as did I. How many of us are simply home cooks, how many lost daughters? How many, like me, shove food in the oven and then run out the door and down the block, in an effort to get as far away from the kitchen as possible?

ULE

No.

4:

O

BEY

Y

OUR

W

HIMS

J

ULIA MAY HAVE BEEN SHELTERED AND UNSOPHISTICATED, BUT

she was also observant and empathic, and when she worked at W & J Sloane in New York and was paid $18 a week, she realized how tough it would be for the average working person to make ends meet.

*

She wasn’t very political, but she saw that there was a lot more to the world than the country club lifestyle in Pasadena.

But for the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Julia might have remained in Pasadena for the rest of her life, golfing, drinking afternoon martinis, throwing parties, playing the role of the pampered spinster daughter of one of the richest, most unfriendly men in town. Part of Julia would have enjoyed

this. She adored Pop, rationalized his obstreperous personality as part of the “he-man” temperament, and from the time she was a child she was not against the pursuit of pleasure. But another part of her longed for hard work and a devotion to something bigger than herself.

When America entered World War II, Julia woke up. When President Roosevelt, whom Pop despised, put out the call for women to join the war effort, Julia followed her first impulse, which was to do … something. One of her abiding qualities was a belief in spontaneity, and the power of acting on a whim.

First, she signed up to volunteer for the local Aircraft Warning Service, but that didn’t quite do it. She worked for the Red Cross and then went on—what the hell—to take the civil service exam. She was determined to do something meaningful, and she applied to join both the WACS (Women Army Corps) and WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service). On her applications she shaved three inches off her height, claiming to be six feet tall, but she was still rejected due to “physical disqualification.”

That hurt. It was one thing to be overlooked for the princess roles, which included fiancée, dewy bride, young wife, and busy mother, and another to be rejected by the military, which, you would think, would welcome someone as fit and strong and, yes, tall, as Julia.

Undaunted, and unwilling to relinquish her first impulse, Julia left Pasadena for Washington, where she was eventually hired as a junior research assistant for the OSS, the precursor of

the CIA. The OSS was itself something of a whim, an ad hoc organization tossed together in June 1942 by the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who admired Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, and felt that upon entering the war, the United States needed its own espionage agency.

Led by General William “Wild Bill” Donovan, attorney, soldier, and football star at Columbia, the agency was staffed mostly by Ivy Leaguers and educated eccentrics with an adventurous streak. Donovan liked to hire people of independent means, under the adorable assumption that the rich were less likely to be bribed than someone who needed the money.

Julia worked in the Registry, where she functioned as an elevated file clerk, keeping track of classified information. Even this is less glamorous than it sounds; basically, she worked from morning ’til night typing index cards.

One day some gossip reached her that the agency was preparing to open an office in India, and Julia, who had never been out of the country except for a day trip to Tijuana, was desperate to go somewhere, anywhere, and India seemed like as good a place as any. Julia was a perfect fit for the OSS. Not only was she a Smithie of means, she was also someone who, as we know, was down on Suggestions and Regulations. They saw her as someone who would be willing to do whatever was necessary.

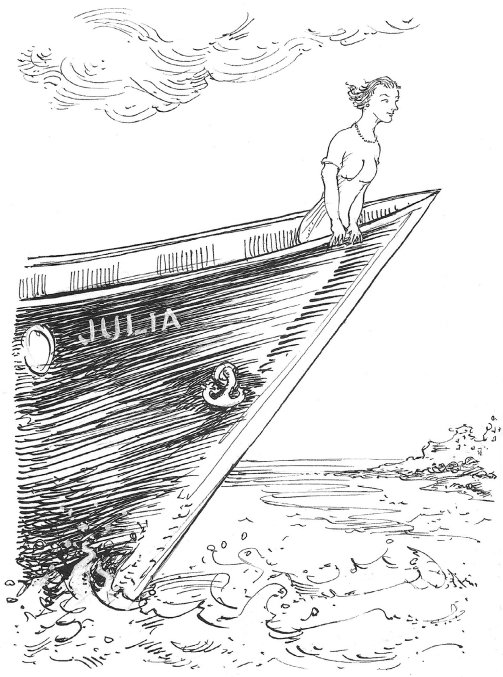

In March 1944, Julia crossed the Pacific aboard the USS

Mariposa,

with three thousand men and eight other “crows,” as the women were called. Their mere presence caused pandemonium, which Julia partially suppressed by spreading the rumor

that they were all missionaries. It took thirty-one days to travel from California to Calcutta, during which Julia played enough bridge to last a lifetime and volunteered as a reporter for the shipboard newspaper. She also had her eyes opened.

Julia knew she was undereducated more or less by choice, but was still throttled by the sheer brain power and sophistication of the “eggheads” she met, first on the ship and then at her eventual postings in Kandy and Kunming, China. Social scientists, psychologists, biologists, historians, and journalists; anthropologist Gregory Bateson, then married to Margaret Mead, became her shipboard drinking buddy. Julia didn’t know it yet, but she’d found her tribe.

The moment the

Mariposa

docked in Calcutta, Julia received word that she was going to be transferred to Ceylon, where a new outpost was being established in Kandy, under the leadership of British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten. Julia would be in charge of setting up the Registry there. She lived in dark, dank quarters that flooded a foot and half every time it rained hard (every afternoon), with a small refrigerator in the living room, on top of which sat a two-burner hot plate.

The longer she did her job, the less she liked it, but she was a trouper. She was her father’s daughter; she believed in leaning into the task at hand. She believed in toughing it out.

She claimed that her long hours left her no time to “scintillate.” This wasn’t quite the case. There was actually plenty of “scintillating” going on; in the small community there were forty males for every female. It was paradise for every single woman but

Julia, who was popular in the way she had always been: a good sport who knew how to have fun, but never a romantic prospect.

Despite her cushy upbringing, Julia possessed a hardy constitution. Before joining the OSS she spent her stamina on the usual upper-middle’s pursuit of entertainment and pleasure. Once she was assigned to head the Registry in Kandy, she discovered that she also possessed a remarkable ability to tolerate monotony and discomfort, often working ten hours a day, six days a week.

Her job was at once critical and murderously dull, tasked as she was with handling, cataloging, indexing, and filing every piece of intelligence that passed through the outpost. The OSS didn’t just gather information, it also carried out myriad clandestine operations that included spreading misinformation, infiltrating local political organizations, acts of counter-espionage, and pretty much everything we’ve come to expect from spies vis-à-vis Hollywood movies; to do all this, the operatives needed sometimes speedy access to material, which is where Julia and her secure-yet-easily-navigated filing system came into play. Throughout her life, Julia downplayed her role in the war, claiming to be a mere file clerk, but her high security clearance tells another story.

OU

N

EVER

K

NOW

W

HAT

Y

OU

M

IGHT

F

IND AT THE

E

ND OF AN

I

MPULSE

One of the great satisfactions of casting our gaze back on the whole of someone’s life is being able to see where the twists and

turns led, and how events given scant attention during their unfolding paved the way for bigger things, sometimes even the biggest things in their lives.

The largest fork in Julia McWilliams’ road was her meeting Paul Child, which never would have happened had she not followed that first whim to answer FDR’s call to arms, and the second whim that led to her putting in her application to be sent to India. All along the way, and without a thought, she followed her heart. But meeting Paul, who not only changed her life but also gave her a brand-new one, was only part of the yield.

By casting her lot in with the OSS, Julia gained confidence, grew up, met the kind of people with whom she would spend the rest of her life, and also, somewhat bizarrely, learned to cope with vast amounts of important bits of information, an underappreciated and homely activity that over time exercised the muscle that, years later, would allow her to build complex recipes. It turned her into a woman who could write a massive, comprehensive, many-thousand-page cookbook that would revolutionize an entire nation’s attitudes about food, cooking, and eating.

HEN TO

H

EED A

W

HIM

The current flavor of positive thinking, which holds that if we just assume something we desperately want is on its way as long as we “put it out there,” has never captured my imagination. Maybe it’s because I spent too many Decembers as a child

fervently hoping, as a common Christmas Eve myth holds, that my dog would talk to me at midnight. Every year I’d wait for Smitty, our surly black dachshund, to open his mouth and hold forth, and every year he sat curled in his bed giving me the side eye. One year, I even curled up beside him on his little plaid bed and started conversing, hoping that maybe he just needed some reassurance; what I got was a snarl instead.

But embracing the power of the whim is a way to shake things up that nudges life into tossing something unexpected in your path. It’s employing your psychic divining rod, allowing it to lead you in a direction where something good, or at least different, is bound to enrich your life.

When I started thinking about whims in general, my first thought, unimaginatively, was the impulse buy. The random candy bar tossed in the grocery basket at the checkout counter; the cute little bracelet thrown atop the sweater at the department store register.

One friend said yes one night when she received a phone call from the Obama campaign asking whether she’d be willing to spend the five weeks leading up to the election working in rural Pennsylvania. On a whim, she said, she left her husband and kids and went.

The best time to heed a whim is when we find ourselves stuck in life, when putting one foot in front of the other is only taking us further away from where we want to go, even though we don’t know where that is. The most accomplished

whim-follower I know is the twenty-year-old son of a friend. Last year, unhappy at college, where he was taking classes that meant nothing to him, he told his parents he was not returning for his sophomore year but was instead moving to Barcelona to live with some family friends. Barcelona was great for a month, until he met some people who sang the praises of Prague, where he went and worked in a coffee shop for a year. There, he also met a girl, whom, after a time, he followed to Seattle, where he is now working in yet another coffee shop and preparing to return to college. This young guy is of the whim-following age, although from what I can tell, most young adults, with the awful pressure on them to decide on a career path by sixth grade, are too frantic with worry to succumb.

The thing about whims is that most of the romantic ones involve a serious outlay of cash. Even hopping in the car for a weeklong road trip across a state or two will set you back a few hundred dollars; here on the West Coast one of the whims that makes you feel like your life is not in a rut—“let’s go to Mexico!”—will set you back thousands. You used to be able to dream about the sun on your face on a Monday, and by Friday your toes were wriggling in the sand at Puerto Vallarta. Now, you’d have to be a part of the 1 percent to afford those tickets.

HE

O

NE

R

ELIABLE

W

HIM

The most obvious whim, given the subject of this book, is what to eat. Every day we’re faced with satisfying a food or cooking

whim. Because when it comes to cooking I’m tortured with ambivalence,

*

my culinary whims are perpetually at war with each other. On a daily basis, I experience opposite urges. I long to both flee the kitchen

†

and devote myself to cooking in Julia-holic fashion. But my behavior is purely whim-driven.

Nothing was left to chance in my mother’s kitchen. She wrote out her weekly menus on Sunday and shopped for the week the next day. Monday night was pork chops; Tuesday night was hamburger pie, a stewed tomato–heavy take on Shepherd’s Pie, with hamburger substituted for lamb, and including frozen French cut string beans; Wednesday night was reserved for “something new”; Thursday was beef stroganoff or beef bourguignon or something that involved simmering; Friday night was Taco Night; Saturday night was Chef’s Salad; Sunday night was pot roast. I live in a permanent state of rebellion against this regimen. The thought of writing out a weekly menu makes me want to tear off my clothes and run down the middle of the street, so slavish and restrictive does it seem. My cooking life is all whim, all the time. Even before my kids went off to college, I would often find myself standing in the middle of

the kitchen at 5:30 p.m. wondering what to make for dinner, waiting for my taste buds to speak up. Sometimes I would race to the corner Whole Paycheck for a rotisserie chicken and broccoli. Sometimes I would throw open the cupboard and make Something with Noodles. Sometimes I would make “breakfast dinner.” Sometimes, in a burst of inspiration, I would make something fabulous, coq au vin or grilled halibut. Sometimes, we would just go out. I prefer to think this refusal to plan means I’ve embraced the French attitude about eating. I’m allowing the spirit to move me. Unfortunately, the spirit is not as epicurean as I would like it to be.