Just a Couple of Days (37 page)

Read Just a Couple of Days Online

Authors: Tony Vigorito

General Kiljoy did not share this view. To be frank, he was freaked out, though in an appropriately disciplined manner. He stood as he watched these events unfold, arms akimbo like a bossy parent, clutching his remote control like a hastily removed belt, trying to decide how many lashes to mete out to his insubordinate children. “What the hell is this?” he snarled, turning to face the rest of us. His eyes were wild, perhaps panicked, and though his brow was furrowed in fury there was a peculiar tranquillity about him. He looked funny, and for the first time I noticed that the crease between his eyebrows formed the inside of a peace symbol.

God only knows how he managed to go so far in the military hierarchy with the footprint of the American chicken stamped on his forehead.

Â

131

According to General Kiljoy's physiognomy book that I found on the bookshelf in the observation lounge, it takes approximately two hundred thousand frowns to etch a permanent crease in your brow. To accomplish this, you would have to

scowl at least nine times a day for sixty years. General Kiljoy had no problem achieving this goal; he probably frowns nine times an hour. But his resulting peace crease must have vexed him considerably. He is certainly aware of this feature. As a self-proclaimed amateur face-reader, he surely must have trained his physiognomy to reveal as little as possible and to mislead as much as possible. After all, he could hardly go parading around the Pentagon with a peace sign chiseled between his eyes and expect to get any respect. That's why he looked so unusual. Current events were wearing on him, and he was losing control of his well-trained facial muscles in the process. He was becoming unbuttoned, expressions long hidden were suddenly flashing their privates to anyone who would look, tossing off their ridiculous cloaks in pathetic exhibitionism.

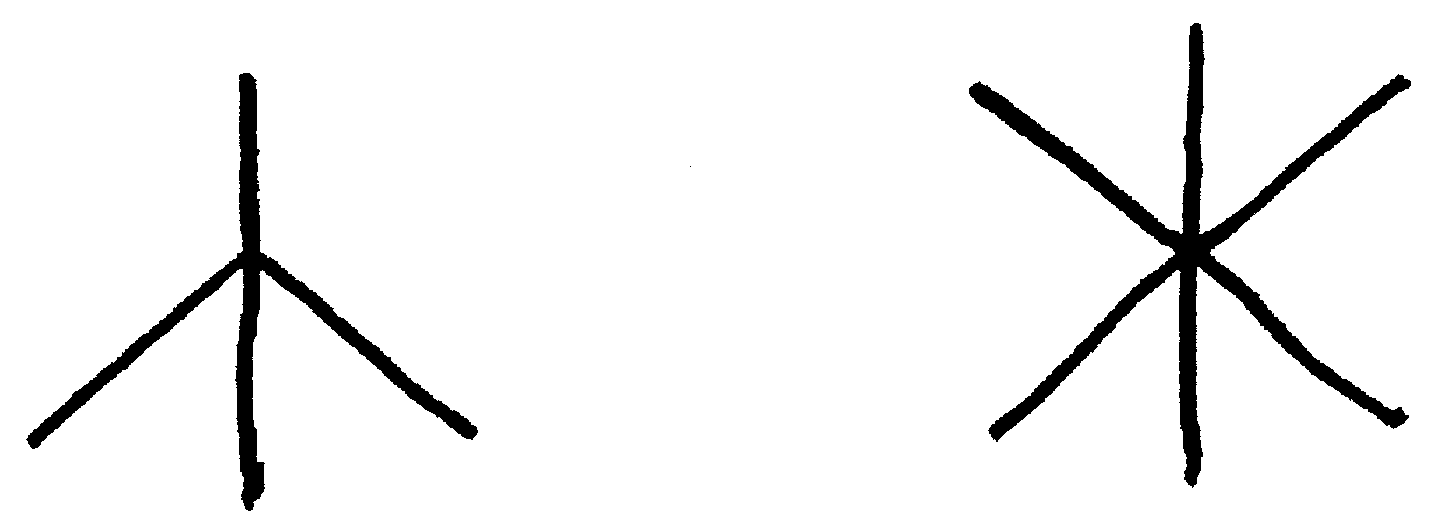

Yes, I am convinced he is aware of his stigmata. The peace crease flashed only briefly, and was quickly replaced by his conventional furrow as he regained some composure. He disguises his accidental groove with an intentional trench, an inverted peace symbol superimposed upon the original. To illustrate, the drawing on the left is his unadulterated brow pucker. On the right side is General Kiljoy's efforts to camouflage his pacifistic countenance. It is his war paint, so to speak.

Â

Â

Admittedly, I am recently suicidal, and thus not entirely of sound mind, and I do not claim to be a face-reader. Nevertheless,

I contend that General Kiljoy has calculated to carve his peace symbol into a stick figure of the Great Seal of the United States, a much less distressing symbol for him to display on his brow.

To see what I mean, look on the back of a dollar bill. The right-hand side of the seal displays a bald eagle with a fistful of arrows in one claw and an olive branch in the other. It is appropriately symbolic, with thirteen leaves and thirteen arrows and thirteen stars and thirteen stripes, and most important for General Kiljoy's purposes, it is rousingly patriotic. And yet, upon closer examination, it is just as exhibitionist as the flower children prancing around his forehead in secret, long-haired and topless, singing “Give Peace a Chance.” The legs of the eagle, after all, are spread-eagle. Indeed, this is the origin of that phrase. Believe it, the legs of our nation are splayed out in both directions like some tasteless but true sexual provocateur. To be fair, the intimate details are discreetly loinclothed by some sort of shield or coat-of-arms negligee, but this only demonstrates an awareness of the innuendo. In any case, whether it is offensive in its gross carnality or admirable for slipping past the censors of a nation first settled by Puritans, whether it represents prudishness or licentiousness, zealous modesty or fucking fanfaronades, no matter its meaning, it is an appropriate third eye for General Kiljoy.

I say this because it is aggressive in either event, and aggression in any form and for any cause was more attractive to him than peace. So, he continued the struggle to keep his sentiments suitably attired, and was partially successful in his insistent tailoring. He at least prevented them from completely dropping their underpants once again. Though he was standing in front of a sidesplitting sideshow of unconsciousness unleashed, he

managed to hold his countenance clad with a bumbling sermon appropriate to the Normandy invasion.

“We,” he grunted after a few spontaneous sputters and miscellaneous mutters. His brow twitched as if it had just been snagged with a fishhook. “We are being threatened,” he continued. “A sinister force has attacked. Our way of life is at stake. Enemies have conspired to destroy our society.” He pointed to the thousands of dancing merries behind him on the screen and smiled like a conceited maggot. “The few must be sacrificed to save the many.”

His platitudinous oration aroused nothing but stirring disgust in me. I was about to mouth off and say as much, and remind him that the few actually numbered in the hundreds of thousands (at least I prefer to think that I was), but Miss Mary preempted my retort with a croaky imperative.

“Look!” she practically puked, sounding like she was speaking through a mouthful of beer-soaked cigarette butts. She pointed at the screen with her cancer stick, looking like she just realized she had shown up for school naked.

The smoldering tip of her cigarette directed me toward the screen. Again, it displayed an unnerving scene of absolute stillness. This time, however, it was not to be dismissed as preposterous. The formerly frenzied hominids had fallen suddenly dormant, but a breeze was clearly visible. This was a real-time video feed, and nothing had paused but the people themselves. It was as if the whip was now vibrating so fast that they appeared to be standing still. They stood with their feet anchored to the ground, hands joined, chests heaving in collective hyperventilation. They stood like this a good long while, until everyone had caught their breath. At least four observers underground were

equally motionless. The crucial difference, however, is that we didn't know what was next. Christ, we didn't even know what was currently happening. They, on the other hand, most certainly did.

Simultaneously, and I mean absolutely simultaneously, no false starts or dillydallies, but at the

exact

same moment, everyone let go of one another's hands and spun completely around. Once, twice, they stopped at two and a half turns, nine hundred degrees, and faced away from the center. By the time the remotecontrolled aircraft had swung around to shift the camera's perspective, the masses had their hands in the air and their mouths open, screaming in ecstatic agony what could only have been the last gasps of ennui, the hysterical funeral cry for a culture whose technology had extended its demise to the point of frothing impatience.

Â

132

Solstices used to puzzle me. Why, I wondered, if the shortest day of the year is on December 22 (give or take a day), why does it continue to get colder even though the days become longer and the sun's rays grow more direct by the day? Conversely, the longest day of the year is around June 22, yet the dog days of summer are in July and August. What accounts for this? Like the penny that I kept forgetting was in my coat pocket all through graduate school, I carried this question around with me for years. I came across it occasionally, but I never got around to putting forth the effort to toss it on the sidewalk or visualize the astrophysics of the solar system. Astronomy was not my specialization, after all, and my academic training had discouraged me

from straying outside my discipline. Instead, I posed it to others when it occurred to me during conversations about the weather. Invariably, they were as mystified as myself. Most had never before considered this climatological contradiction.

I was disappointed when I finally received the answer. It was during a cold snap in February, and it came from a clerk at a fast-food restaurant. After being charged $1.01 for a cheeseburger (94 cents plus taxâcouldn't they have made it an even dollar, for chrissakes?) and remembering at last that I had a penny in my coat, I was unable to find it and had to break a twenty instead. I was bummed. What purpose did that persistent penny serve if I never succeeded in using it? Such anticlimax was doubly experienced when I commented on the cold and proceeded to complain absentmindedly about the aforementioned contradiction. He had the answer, and it had little to do with astronomy and much to do with meteorology. “Thermal lag,” he said. “Air and water currents warm and cool at a pace slower than the phases of the sun. Air and water temperatures determine immediate climate patterns, not the sun's position in the sky. It's like the noonday sun; it's not yet the heat of the day.”

Oh.

Today anyway, December 21, the winter solstice, when the angle of the sun is at its southernmost point, when the sun gives the northern half of our planet the cold shoulder, on this particularly beautiful, warm, and sunny darkest day of the year, on this watershed day something supremely more celestial occurred among the animated descendants of stardust assembled around our lifeless city.

They ran for it.

Â

133

“Remember, man, dust you are and to dust you shall return.” Father Whippet, no doubt hungover from his own private Fat Tuesday party at the rectory, used to mumble these words to me just before smudging soot on my grade-school forehead on Ash Wednesday. He was only partially correct with his blessing, for he left out the stars. We are

stardust

, not just dust. The entire solar system, from its life to its rocks, ultimately formed from different molecular patterns of stardust. When we die, we bite the stardust.

Blip said it well one sunny vernal equinox just after he focused a prism's rainbow on my forehead. “When you're born, you pass through the prism. Life is a rainbow, an infinite spectrum of radiant souls. But remember, man, light you are and to light you shall return.”

Â

134

I once read about a weirdo who maintained a soap bubble for over a year. Looking closely at a bubble, you can see the swirling rainbows flowing downward. Gravity. In the absence of a collision, the soap will drip off the bubble until it can no longer maintain its surface tension, and it will pop. So, in order for this bubblehead to keep his precious sphere of suds alive, he had to keep feeding it soap. How he managed to do this I cannot recall; only the memory of his ineffable waste of time continues to loiter about the corners of my mind.

Point being, society is like a bubble, kept alive by continually feeding it languageâhence the strategy behind the Pied Piper virus. Stop feeding the bubble, and it will explode. No conflagration, no destruction, just an inaudible pop, and no trace

of its existence remains. But why are we so hung up on feeding the bubble in the first place? Why participate in such a thankless task? Perhaps because it provides a very convincing illusion of meaning, security, purpose, and order, and is therefore an excellent place to hide from reality. Those who labor the most diligently on maintaining and defending the bubble are merely the most gutless among us. Cowardice makes for a good citizen, it seems.

In any case, when the circle around the city broke huddle and people ran in their own radial directions, it was not clear whether the bubble had popped or if it was expanding to encompass all that it had heretofore neglected. Perhaps it was a little of both. The bubble burst, to be sure, yet all available evidence indicated that the Pied Piper virus had somehow backfired. It was like a trick gun that not only blew up in its user's face, but also invigorated its intended victim. What of this order, this coordination, this choreography? This was not mass anomie, pandemonium, and normlessness, but its perfect opposite. The biggest, wildest, most mind-blowing game of Ring around the Rosy ever held had come to an extraordinary finale, and instead of falling down dead the players had exploded outward into God-knows-what.

Ring around the Rosy, as you should know, is another one of our blind habits that has persisted brainlessly for generations, since the days of the Black Death, according to some.

Â

Ring around the rosy,

Pockets full of posy,

Ashes, ashes,

We all fall down.

Â

Reportedly, the nursery rhyme is describing the rings of dried blood those afflicted with the plague got under their skin, herbs hoped to treat it, and the burning corpses of more than half the humans on the Eurasian continent. A playful memoir to the largest catastrophe in Western human history, but now some brash upstart plague had rewritten the words.

Â

Ring around our city,

Laughing off our pity,

Dancing, dancing,

We all get down.

Â

Or something to that effect.

Just two months ago, this city had a little over a million inhabitants. If, as is claimed, a tenth of the residents perished as an indirect result of the outbreak, some nine hundred thousand children of stardust made their mother proud today and went supernova. To attain supernova status is the highest ambition of a star (and is, incidentally, something our good sun will never itself achieveâit's not big enough). In exploding, a star achieves a luminescence up to one hundred million times brighter, and then begins the long process of coalescing into something entirely new. An alternative is to collapse into a miserable black hole, a mass of matter so dense that not even light can escape. How pleased our sun must have been to witness its naughtiest children escape their own vortex of avarice and outshine even her.