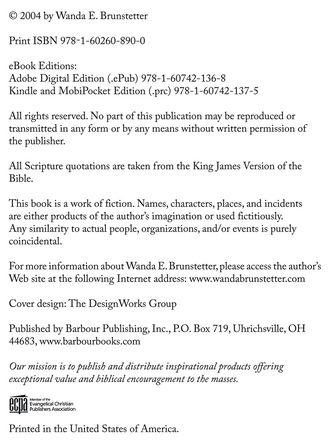

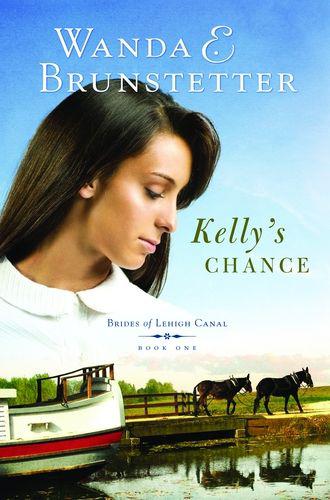

Kelly's Chance

Wanda E Brunstetter

Table of Contents

DEDICATION/ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To my husband, Richard,

born and raised in Easton, Pennsylvania, near the Lehigh Canal.

Thanks for your love, support, and research help.

To Char and Mim,

my brother-in-law and sister-in-law.

Thanks for your warm hospitality as we researched this book.

Lehigh Valley, Pennsylvania—Spring 1891

***

Kelly McGregor trudged wearily along the towpath, kicking up a cloud of dust with the tips of her worn work boots. A size too small and pinching her toes, they were still preferable to walking barefoot. Besides the fact that the path was dirty, water moccasins from the canal sometimes slithered across the trail. Kelly had been bitten once when she was twelve years old. She shuddered at the memory ... Papa cutting her foot with a knife, then sucking the venom out. Mama following that up with a poultice of comfrey leaves to take the swelling down, then giving Kelly some willow bark tea for the pain. Ever since that day, Kelly had worn boots while she worked, and even though she could swim quite well, she rarely did so anymore.

As Kelly continued her walk, she glanced over her shoulder and smiled. Sure enough, Herman and Hector were dutifully following, and the rope connected to their harnesses still held taut.

“Good boys,” she called to the mules. “Keep on comin’.”

Kelly knew most mule drivers walked behind their animals in order to keep them going, but Papa’s mules were usually dependable and didn’t need much prodding. Herman, the lead mule, was especially obedient and docile. So Kelly walked in front, or sometimes alongside the team, and they followed with rarely a problem.

Herman and Hector had been pulling Papa’s canal boat since Kelly was eight years old, and she’d been leading them for the last nine years. Six days a week, nine months of the year, sometimes eighteen hours a day, they trudged up and down the towpath that ran alongside the Lehigh Navigation System. The waterway, which included the Lehigh Canal and parts of the Lehigh River, was owned by a Quaker named Josiah White. Due to his religious views, he would not allow anyone working for him to labor on the Sabbath. That was fine with Kelly. She needed at least one day of rest.

“If it weren’t for the boatmen’s children, the canal wouldn’t run a day,” she mumbled. “Little ones who can’t wait to grow up so they can make their own way.”

Until two years ago, Kelly’s older sister, Sarah, had helped with the mules. Then she ran off with Sam Turner, one of the lock tender’s boys who lived along their route. Sarah and Sam had been making eyes at each other for some time, and one day shortly after Sarah’s eighteenth birthday, they ran away together. Several weeks later, Sarah sent the family a letter saying she and Sam were married and living in Phillipsburg, New Jersey. Sam had gotten a job at Warren Soapstone, and Sarah was still looking for work. Kelly and her folks hadn’t seen or heard a word from the couple since. Such a shame! She sure did miss that sister of hers.

Kelly moaned as she glanced down at her long, gray cotton skirt, covered with a thick layer of dust. She supposed the sifting dirt was preferable to globs of gritty, slippery mud, which she often encountered in early spring. “Long skirts are such a bother. Sure wish Mama would allow me to wear pants like all the mule boys do

.

”

In the past when the wind was blowing real hard, Kelly’s skirt billowed, and she hated that. She’d solved the problem by sewing several small stones into the hemline, weighing her skirt down so the wind couldn’t lift it anymore.

Kelly looked over her shoulder again, past the mules. Her gaze came to rest on her father’s flat-roofed, nearly square, wooden boat. They were hauling another load of dark, dirty anthracite coal from the town of Mauch Chunk, the pickup spot, on down to Easton, where it would be delivered.

Kelly’s thoughts returned to her sister, and a knot rose in her throat. She missed Sarah for more than just her help. Sometimes when they’d walked the mules together, Kelly and Sarah had shared their deep-est desires and secret thoughts. Sarah admitted how much she hated life on the canal. She’d made it clear that she would do about anything to get away from Papa and his harsh, stingy ways.

Kelly groaned inwardly. She understood why Sarah had taken off and was sure her older sister had married Sam just so she could get away from the mundane, difficult life on the Lehigh Navigation Sys-tem. It didn’t help any that Kelly and Sarah had been forced to work as mule drivers without earning one penny of their own. Some mule drivers earned as much as a dollar per day, but not Kelly and her sister. All the money they should have made went straight into Papa’s pocket, even if Mama and the girls had done more than their share of the work.

In all fairness, Kelly had to admit that, even though he yelled a lot, Papa did take pretty good care of them. He wasn’t like some of the canal boatmen, who drank and gambled whenever they had the chance, wasting away their earnings before the month was half over.

Kelly was nearing her eighteenth birthday, and even though she was forced to work without pay, noth-ing on earth would make her marry someone simply so she could get away. The idea of marriage was like vinegar in her mouth. From what she’d seen in her own folks’ lives, getting hitched wasn’t so great, any-way. All Mama ever did was work, and all Papa did was take charge of the boat and yell at his family.

Tears burned in Kelly’s eyes, but she held them in check. “Sure wish I could make enough money to support myself. And I don’t give a hoot nor a holler ’bout findin’ no man to call husband, neither.”

Kelly lifted her chin and began to sing softly, “Hunks-a-go pudding and pieces of pie; my mother gave me when I was knee-high.... And if you don’t believe it, just drop in and see—the hunks-a-go pudding my mother gave me.”

The tension in Kelly’s neck muscles eased as she began to relax. Singing the silly canaler’s tune always made her feel a bit better—especially when she was getting hungry and could have eaten at least three helpings of Mama’s hunks-a-go pudding. The fried batter, made with eggs, milk, and flour, went right well with a slab of roast beef. Just thinking about how good it tasted made Kelly’s mouth water.

Mama would serve supper when they stopped for the night, but that wouldn’t be ’til sundown, several hours from now. When Papa hollered, “Hold up there, girl!” and secured the boat to a tree or near one of the locks, Kelly would have to care for the mules. They always needed to be curried and cleaned, in particular around Herman and Hector’s collars where their sweaty hair often came loose. Kelly never took any chances with the mules, for she didn’t want either of them to get sores or infections that needed to be treated with medicine.

After the grooming was finished each night, Kelly fed the animals and bedded them down in fresh straw spread along the floor in one of the lock stables or in their special compartment on the boat. Only when all that was done could Kelly wash up and sit down to Mama’s hot meal of salt pork and beans or potato and onion soup. Roast beef and hunks-a-go pudding were reserved for a special Sunday dinner when there was more time for cooking.

After supper when all the dishes had been washed, dried, and put away, Kelly read, drew, and sometimes played a game. Mama and Papa amused themselves with an occasional game of checkers, and sometimes they lined up a row of dominoes and competed to see who could acquire the most points. That was fine with Kelly. She much preferred to retire to her bunk in the deck below and draw by candlelight until her eyes became too heavy to focus. Most often she’d sketch something she’d seen along the canal, but many times her charcoal pictures were of things she’d never seen before. Things she’d read about and could only dream of seeing.

On days like today, when Kelly was dog-eared tired and covered from head to toe with dust, she wished for a couple of strong brothers to take her place as mule driver. It was unfortunate for both Kelly and her folks, but Mama wasn’t capable of having more children. She’d prayed for it; Kelly had heard her do so many times. The good Lord must have thought two daughters were all Amos and Dorrie McGregor needed. God must have decided Kelly could do the work of two sons. Maybe the Lord believed she should learn to be content with being poor, too.

Contentment. Kelly didn’t think she could ever manage to achieve that. Not until she had money in her pockets. She couldn’t help but wonder if God cared about her needs at all.

Herman nuzzled the back of Kelly’s neck, interrupting her musings and nearly knocking her wide-brimmed straw hat to the ground. She shivered and giggled. “What do ya want, ol’ boy? You think I have some carrots for you today? Is that what you’re thinkin’?”

The mule answered with a loud bray, and Hector followed suit.

“All right, you two,” Kelly said, reaching into her roomy apron pocket. “I’ll give ya both a carrot, but you must show your appreciation by pullin’ real good for a few more hours.” She shook her finger. “And I want ya to do it without one word of complaint.”

Another nuzzle with his wet nose, and Kelly knew Herman had agreed to her terms. Now she needed confirmation from Hector.

***

Mike Cooper didn’t have much use for some of the new fangled things he was being encouraged to sell in his general store, but this pure white soap that actually floated might be a real good seller—especially to the boatmen, who seemed to have a way of losing bars of soap over the side of their vessels. If Mike offered them a product for cleaning that could easily be seen and would bob like a cork instead of sinking to the bottom of the murky canal, he could have a bestseller that would keep his customers coming back and placing orders for “the incredible soap that floats.”

Becoming a successful businessman might help him pursue his goal of finding a suitable wife. Ever since Pa had died, leaving him to run the store by himself, Mike had felt a terrible ache in his heart. Ma had gone to heaven a few years before Pa, and his two brothers, Alvin and John, had relocated a short time later, planning to start a fishing business off the coast of New Jersey. That left Mike to keep the store going, but it also left him alone, wishing for a helpmate and a brood of children. Mike prayed for this every day. He felt he was perfectly within God’s will to make such a request. After all, in the book of Genesis, God said it wasn’t good for a man to be alone, so He created Eve to be a helper and to keep Adam company. At twenty-four years old, Mike thought it was past time he settled down with a mate.

Mike’s biggest concern was the fact that there weren’t too many unattached ladies living along the canal. Most of the women who shopped at his store were either married or adolescent girls. One young woman—Sarah McGregor—was the exception, but word had it she’d up and run off with the son of a lock tender from up the canal a ways. Sarah had a younger sister, but the last time Mike saw Kelly, she was only a freckle-faced kid in pigtails.