Ken Kuhlken_Hickey Family Mystery 02

Read Ken Kuhlken_Hickey Family Mystery 02 Online

Authors: The Venus Deal

Tags: #FICTION / Mystery & Detective / General

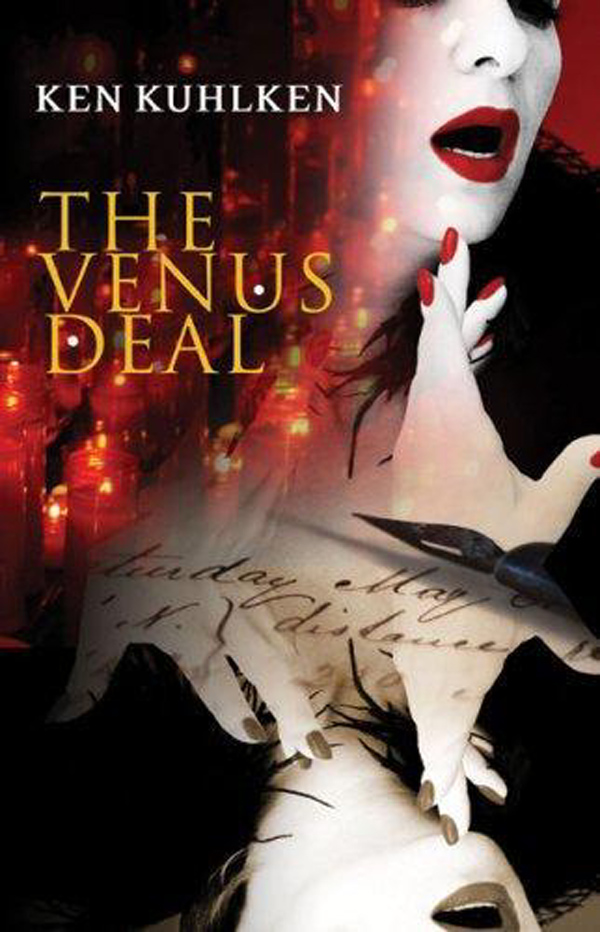

The Venus Deal

Copyright © 1993, 2007 by Ken Kuhlken

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2006940854

ISBN-13 Print: 978-1-59058-408-8 Trade Paperback

ISBN-13 eBook: 978-1-61595-113-0

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in, or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

“Lover Man” words and music by Jimmy Davis, Roger “Ram” Ramirez, and Jimmy Sherman Copyright 1941, 1942 by MCA Music Publishing, a division of MCA Inc., New York, N.Y. 10019. Copyright renewed. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Poisoned Pen Press

6962 E. First Ave., Ste. 103

Scottsdale, AZ 85251

For my half sister, Marilou, wherever you are,

in memory of our father, Tom Hickey’s best pal

Contents

Many thanks to Larry Clinger; Sylvia Curtis; Evangeline Garfield; Jojo Field; Corinne Hunt; Woody and Bob Halley; Dennis Lynds and Gayle Stone, whom I failed to thank in

The Loud Adios

; Ivy Rivard; Denver police technician Mike Shonk; and Vera and Ralph Steinhoff, not only for facts and ideas but for the love you’ve given my kids and me.

Ten days ago, before Cynthia Moon had run off on her mysterious errand, Clyde McGraw’s orchestra blew like crusading angels. Now they sounded like they’d spent the weekend playing at a funeral and they were battling just to stay alive for the next one. The four-man horn section might’ve had lung disease; the two violins, string bass, electric guitar, and drummer looked arthritic. Clyde could barely lift his baton. The only one who appeared alive was the singer, Billy Martino. Dressed in a burgundy dinner jacket, slippers to match, black pin-striped trousers, his shiny hair poofed up high except for the spit curl that adorned his forehead, he crooned “White Christmas” as passionately as a French legionnaire condemned to an outpost in Tunisia.

Tom Hickey sat on a stool, leaning on the bar at the opposite end of the nightclub, across the dance floor under its flickering chandelier and beyond the dining room furnished with oak tables and leather-upholstered booths. Hickey was a big man, shoulders so broad he didn’t use padding in his suit coats, or else he’d appear monstrous. He had a ruddy complexion and thin, scraggly hair beginning to gray. His nose was long, his chin cleft, his eyes steady and quick, azure blue. He gazed around at the clientele.

In the half-empty dining room were a few couples, two small gangs of secretaries, a family with whiny kids. They ate and drank heartily, disregarding Martino. The only couple on the dance floor had stopped to gab. One fellow at the bar sat with his hands over his ears.

All through November, until ten days ago, every night the place had been jammed. At midnight the line outside used to run a short block down Fourth Street toward Broadway. Over the weeks since Clyde discovered Cynthia Moon, word had reached L.A. Carloads of men trekked a hundred miles to gawk at her.

By now the military brass, flyboys, enlisted fellows who’d been saving all month or won big at poker—the crowd that until last week made Rudy’s Hacienda the hottest club in town—had found better action than Martino.

As “White Christmas” faded, Hickey admired the rich baritone, no matter if he made Billy for a vain weasel who wouldn’t know an honest emotion if it tried to strangle him. He faked the passion as well as most crooners. But he wasn’t fooling this crowd. They must’ve been saving their goodwill for Christmas, eleven days off.

Christmas and New Year’s Eve were already booked full. If Cynthia didn’t show by then, Hickey might pack up his wife and daughter, flee up to Lake Arrowhead, and leave his business partner to make the apologies. Castillo deserved the aggravation.

When the singer bowed, a few paws clapped dutifully. A kind secretary whistled. A man at the bar, three seats from Hickey, hollered, “Send the pansy back to Mars.”

Hickey sighed, rose, and stepped in front of the loudmouth, a tipsy banker with jowls that quivered and a bow tie. Hickey’d seen him around, usually in the Playroom in the basement of the U. S. Grant Hotel. “Be nice,” Hickey said. The banker held his smirk about a second, then gulped and wilted.

Returning to his stool, Hickey wondered if a host who owned the place ought to let himself act like the bouncer. His partner would’ve sent the doorman over. Castillo wouldn’t risk getting his pointy nose busted—if the Cuban was going to fight a guy, he’d sneak behind him first.

On nights like this one, and the whole past week, when the best they could hope was to break even, Hickey wondered why he’d gone into business with a shark like Paul, as if he didn’t find enough trouble in his day job, junior partner in Hickey and Weiss, Investigations.

The musicians got livelier as they hopped off the stage, lighting cigarettes and heading outside for air or to a booth to charm a secretary and take her for a stroll around the block.

Clyde McGraw dragged his patent-leather shoes across the dance floor, his head down, mumbling like a priest. Without looking up, he shuffled around the tables and booths, nudged the stool next to Hickey out of his way, and leaned both elbows on the bar, chin in his hands. “Double manhattan.”

Clyde had skin like milk chocolate, mahogany brown hair parted in the middle, a gray-flecked pinstripe mustache. He wore a beige cotton suit, his lime green silk shirt buttoned at the collar, jeweled rings on six of his long pianist’s fingers. Finally, he raised his head and turned his bloodshot eyes on Hickey. “Mister Castillo comes back in the kitchen while I’m taking supper, says if the girl don’t show by the weekend, we gonna be blowing on the corner with the Salvation quartet. Merry Christmas, no? I tell him, ‘We got a contract till Valentine’s Day, if you recall.’ The cat winks, that’s all. I jump on the phone, gripe to Arlo down at the union. He’s got to check with somebody. When he rings me back, here’s what I get. ‘Somebody mess with Paul Castillo, somebody be hurting.’ Looks like you got a mob behind you, Tom. That a fact?”

“Naw,” Hickey said, and meant it, but a grain of doubt made him shiver. He’d checked as far as he could on Paul Castillo, and the man came up clean. But that was a half year ago, and a dozen times since, Castillo had miraculously got what or whoever he wanted in spite of the wartime rationing. Creamery butter, lobsters still shivering from the waters off Maine, a quintet of Stan Kenton’s musicians away from their booking at the Pacific Ballroom.

“You let him break the contract, Tom?”

“It’s a tough business,” Hickey said. “Guys’ll pay a cover to see the girl. All you got now’s Martino. Maybe we have to drop the cover charge, we don’t make enough to pay a whole union orchestra, we got to find a three-, four-man combo instead.”

“Girl wasn’t specified in the contract, Tom.”

“Maybe she was implied.”

“Ah, you gonna step on me too.”

“Not if I can help it,” Hickey said. “You go find the girl, or get another one like her.”

“Like her, yeah.” Clyde turned to his drink, ate the cherry. “Where I’m gonna find one like her? No such thing. She’s a crackerjack, Tom. I’m losing my wits, ringing up her landlady, fretting, you’d think I was her pop.”

Hickey snatched his pipe and tobacco pouch out of a coat pocket, filled the pipe, tamped, and fired it up. “Where’s she live?”

McGraw’s eyebrows lifted, his chin jiggled. “There we go, you find her. That’s your game.”

“Yeah,” Hickey said. “For twenty a day, plus.”

McGraw wasn’t the only fellow worried about Cynthia Moon. An admiral, pilots enough to make a squadron, ensigns, corporals, attorneys, stockbrokers, a San Diego Padres shortstop who’d led the Pacific Coast League in stolen bases—men pestered Hickey about her every night. The orchestra, in mourning for the crowds that used to jump and shimmy with the music when they had Cynthia, now could turn “Goody, Goody!” into a lament.

Each evening since she’d failed to show after the week off Clyde gave her, Hickey’d met the band as their cars pulled up, hoping Cynthia would climb out of one. Whenever he called his answering service, the message he most hoped for was about the girl.

A tremendous loss, Cynthia Moon. A slender, high-cheeked face, milky skin, emerald green eyes, all of which set off her wavy red hair, a mix of burnt orange and auburn. Smallish mouth, lips full and restless. She moved regally, self-conscious but poised as if it were natural law that whatever she did would be admired and imitated. In heels she stood over six feet, eye to eye with Hickey. Most of her was legs. Modest breasts and hips, a small waist, broad, square shoulders, a long, graceful neck usually trimmed with pearls.

Her voice was sultry, smooth, and aloof when she spoke to the men who sent her flowers, offered her drinks, invited her for weekends at swank resorts up the coast or in Palm Springs. She kept the flowers, turned down the drinks, fielded and tossed off the seductions without blinking.

Onstage, it seemed her insides caught fire, as if she were in love or pregnant. When she sang old standards, you heard passions in them that had slipped past you before. Listening to Cynthia Moon, you could believe she’d been everywhere, done everything, yet magically kept her innocence. Nobody would’ve guessed she was only seventeen.

The age was a secret. McGraw had confessed it to Hickey and Paul Castillo after the audition, before they wrote the contract for three months, six nights a week. Hickey’s first impulse was to send Clyde packing, but Castillo outtalked him. The girl was a star on the rise. Boys her age were screaming at God in the Tunisian desert, on the beaches of New Guinea and Guadalcanal, and the cops had bigger chores than running kids out of nightclubs. Besides, Castillo said, if she got them in a jam, he’d talk to a pal of his.

For three weeks Hickey watched her sing and gabbed with her between the last set and closing time, after Castillo disappeared, the way he always did about midnight. Hickey drank scotch while the girl sipped ginger ale. He would’ve given her a cocktail or two if she’d wanted, but she never did. He guessed she feared losing her head. From the talking and because they both had music inside them, he’d gotten to know her at least as well as anyone seemed to. Slight gestures—cocking her head at the wrong instant, a tiny grimace where there should’ve been a smile, a word out of place—told him she was hardly the unflappable, worldly character she played. She was a girl. Only something, maybe the war, made her grow up too soon.

Hickey wheeled his ’41 Chevy coupe, a frisky little number with a radio and camel hair upholstery, out of his reserved spot in the public parking behind Rudy’s, tossing a quarter to Skeeter, a buck-toothed kid wearing a Yankees cap, who kept an eye on the cars. Hickey turned up Fourth Street, driving slowly until his eyes dilated. Like all the West Coast cities, San Diego was running on dim so the Japs would have to squint to bomb it. Neon signs, streetlights, theater marquees—all dark. The only lights seeped from behind shaded windows and from the bottom half of headlamps painted brown or black across the top.

At Broadway—the intersection between his office, above the Owl Drugstore, and the U. S. Grant Hotel—he cut right, toward the docks. The view ahead looked as if mobs of looters had invaded a ghost city. Not a single Christmas light sparkled. Two years ago, before Pearl Harbor, you would’ve seen moms out gift shopping, tugging the kids by the hands so they wouldn’t stagger into traffic while gawking above at the giant red stars and strings of pastel lights that hung across Broadway four stories up, or at the lighted trees on every corner from the harbor to a mile inland. Dads would’ve been carrying armloads of glittery packages out of Marston’s. Carols would’ve echoed up side streets from blocks away.

Christmas season 1942, if you went out after dark, more likely it was to drink or pray than to shop. All that stayed open after dusk were nightclubs, movies, coffee shops, the burlesque and peep-show arcades, tattoo parlors, the bus station. The chiropractor who moonlighted in abortions, across the hall from Hickey’s office.

The sidewalks, dark except when moonlight sneaked through a break in the foggy clouds or where the glow spilled out of a doorway, were jammed with soldiers and sailors, country girls who’d moved to the city to type and wear scarlet lipstick, burly stevedores, Swedes, Mexican hustlers, salesclerks wrapped in shawls and mittens. Most every kind of adult human except bigshots milled around the Horton Plaza movie houses, smoking, storytelling, flirting, nipping from flasks while they waited sometimes three hours to watch a two-hour-long movie at the Cabrillo or Plaza Theater.

From a corner on the north side of Fifth and Broadway, a gospel quintet of Negroes in top hats and capes sang, “O Holy Night.”

Hickey paused too long at the stop sign, listening. From behind him a horn trumpeted. He jumped an inch and snarled. One of the fastest ways to earn Hickey’s wrath was to blast him with a horn. Even a toot sparked his temper these days, since he’d bought into Rudy’s, begun working eighteen-hour shifts, and watched Madeline turn from his darling to a nag, as though she’d finally lost hope and started hunting for reasons to forsake him.

He knocked the shift lever into neutral, pulled on the hand brake, bounded out, and strode toward the Buick behind him. The horn blower resembled a tortoise. Wide, flat mouth, head sinking fast between his shoulder blades. He reached out and slapped down the locks on both doors. Hickey walked up close, grinned at the fellow, turned back, and strolled to the front of his Chevy. He leaned on the fender and watched the carolers.

“

A thrill of hope

,

the weary world rejoiceth

,

for yonder breaks

a new and glorious…

”

The Buick shot around him, the tortoise-man yelling, “I got your number, hot stuff, and I’m calling a cop.”

Hickey ambled into his car and continued down Broadway. By the Greyhound station beneath the Pickwick Hotel on the corner of Second, he got stalled by about a hundred marines parading across the street to join the line outside the Spreckels Theater. Six blocks farther, at the far end of Union Station, bells clanged, red lights flashed, and the arm dropped in front of the railroad tracks. The Santa Fe crept past, slowing to deliver its load to the docks at the foot of Market Street. Hickey counted forty-six bin cars full of oranges, carrots, lettuce, and onions.

He cut north on Harbor Drive, past the docks where tuna fishers sprayed down their nets, and workers like gangs of ants plodded with their crates and skids stacked with boxes up and down the gangway of a merchant ship flying the Union Jack. Ships usually anchored in midharbor until after dark when they got tugged in to load, as if the Japs had no spies or maps and couldn’t judge except in daylight where the docks and warehouses might be. Hickey figured the Port District ought to build docks in the south bay, as far down as you could take the ships without them running aground, and spread the action instead of clustering it all within a mile of downtown where a single raid of half the bombs they used on Pearl would ravage the tuna fleet, flatten the heart of the city, sink a dozen ships, and knock out aircraft factories, three military bases, and Lindbergh Field.

No one consulted Hickey on military strategy. Except when Admiral Van Vleet asked him whether to order the filet or New York cut, and Colonel Creaser sought his opinion about what kind of flowers Cynthia Moon would like best, the military had passed on its opportunity to benefit from Hickey’s wisdom. Last year, along with the millions of other patriots who’d swarmed the recruiting offices in the weeks following Pearl Harbor, Hickey had volunteered for the navy. They ran him through a physical and determined that thirty-five was too old, at least for a borderline diabetic.

The same week they’d turned him down, a chilly evening in March just before dark, he’d been fishing off his pier on Mission Bay when Madeline called him inside. To introduce a fellow she’d brought home from the Del Mar Club in La Jolla. He was new in town, had plans, needed a partner. A couple hours and tumblers of scotch later, Hickey decided that if Uncle Sam didn’t want him, he ought to go ahead and make a killing off the war, like any bigshot would.

Four thousand dollars and a couple months of labor—carpentry he’d learned on weekends and on vacation from high school when he was trying to save the money to study at USC—he’d sunk into Rudy’s. They got the place ready about the time half the poor sailors and GIs who remained stateside landed in San Diego. During 1942 the population had doubled. After six months, Hickey’s share of the club was worth ten times what he’d invested. It added a decimal to his income. At Rudy’s he could make two, three hundred dollars on a good night, just for gabbing with folks, mediating a squabble between the chef and a waiter, watching Cynthia Moon. If he could find her.

Beneath a cargo plane that sounded doomed to explode before it dropped the last few hundred feet to Lindbergh Field, Hickey swung onto Pacific Coast Highway. Just as he’d hit cruising speed, he had to slow for a wailing fire truck that crossed Harbor Drive in front of him and turned in to the main gate of Consolidated Air, a quarter mile of factory surrounded by a cement wall

and

a chain fence, all of it draped in camouflage netting, even the walking bridge over the highway. Through the open gate, Hickey caught glimpses of welders’ torches sparking. He drove under the bridge through the echoing whack and clang of machines.

He turned on Bay Street, rattled across the tracks and a couple blocks east, cut north again on India Street, and rolled over the hill into Old Town, where the houses were mostly Victorian, the landscaping desert—hillsides of aloe and agave, palm trees, stunted yuccas that barely survived the fog.

Four-sixty-three Jones Street was a shabby Victorian a block and a half up Presidio Hill, high enough to overlook the harbor, the naval training center and beyond, the private marinas of Shelter Island, and Moorish villas on the inland slope of Point Loma. The paint had faded to appear like whitewash tinting the redwood slats. The green trim was chipped, spotted with white primer. Each window had a different style and shade of curtain, most of them frilly. The balconies were strung with clotheslines, one adorned with ladies’ slips, pearl-colored in the mist, hanging all in a row like a chorus line.

Hickey climbed the steps, crossed the rickety porch, and tapped the knocker on the door. Heels clicked inside. The door flew open and a doll face gazed at him. A button nose. Eyes glittering like polished china. Cherry gumdrop lips. The girl wore a green dress with hat and gloves to match.

“It’s about time. Oh.…” She recoiled as though Hickey held an ax raised.

He stepped into the foyer. After he introduced himself and got the girl’s name, Loraine, he apologized for being the wrong guy and asked for Mrs. Ganguish, the name Clyde had given him.

Loraine sauntered down the hallway, knocked on the second door. In the minute or two Hickey waited, three young women appeared—two at the top of the stairs, one peeking out of the first door in the downstairs hallway. Each of them eyed him closely and brightened for a second before she disappeared. Since the war had carried most of the young men overseas, those left behind, even if they weren’t so young, got attended to. Hickey was no pretty-boy, but his face was strong, clothes fit him well, his manners were smooth.

The place, Hickey decided, was either a storybook whorehouse or one of the dormitories spinsters or widows ran for young ladies on their own, shelter from the cruel world full of devious men. Loraine had gone into the parlor, probably to watch the clock. It was 9:30. If the dame who ran this home was as strict as some Hickey’d known, Loraine’s boyfriend could show now and only get a half hour to give her candy, beg her forgiveness, and smooch on the porch before her curfew.

A woman stepped out of the second doorway in the hall. Mexican or Spanish, small, tough. Her arms swung stiffly. She had eyes of pure white and obsidian black, breasts like the mother of twenty, long black hair pulled back sternly.

Hickey gave his name, offered his hand, said he was looking for Cynthia Moon.

The woman squeezed his fingers hard. “Call me Dolores. You run that bar?”

“Rudy’s is a supper club.”

“You serve booze?”

“Sure.”

“It’s a bar.”

“You got me. Cynthia around?”

The woman shook her head wearily, turned, walked into the parlor, and collapsed into a faded love seat. She motioned to the sofa where Loraine knelt on the cushion, leaning on the backrest and staring through the front porch window. Hickey took a seat beside her.

“All the time I’m worrying about my girls,” Mrs. Ganguish said. “If they don’t come home two hours after they supposed to, I don’t get no sleep. You think they care? Not much, they don’t. Cynthia, she promises to come home last Friday. Maybe somebody kills her, I don’t know. Say, how many of you guys I gotta tell this to?”

“Somebody else’s been asking?”

“Sure, this crazy man calls me over and over. Every time I forget to worry, a couple minutes later, he calls. Now you?”

“Crazy man?”

“His name’s Clyde.”

“McGraw. Why do you say he’s crazy?”

Dolores’ hand sliced the air in front of her face. She wagged her head as if remembering some knowledge too hard or complex to explain. “Musicians, I know about them.”

“Uh-huh. How about a boyfriend? She got one?”

“No, sir.”

“Girlfriends, family?”

Hearing the shuffle of bare feet and skirts rustling, Hickey glanced through the parlor door. Beyond the foyer, atop the stairs, two young women leaned on the rail. One looked dwarfish, not so short but as if she’d once been taller and gotten squished. The other had a crop of golden curls bouncy as springs. When Hickey spotted them looking, they turned to each other, bent into a huddle, and whispered. A second later Loraine slapped the back of the couch. “The hell with him!” She jumped up and rushed out of the room, up the stairs.