Kennedy's Last Days: The Assassination That Defined a Generation (15 page)

Read Kennedy's Last Days: The Assassination That Defined a Generation Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly

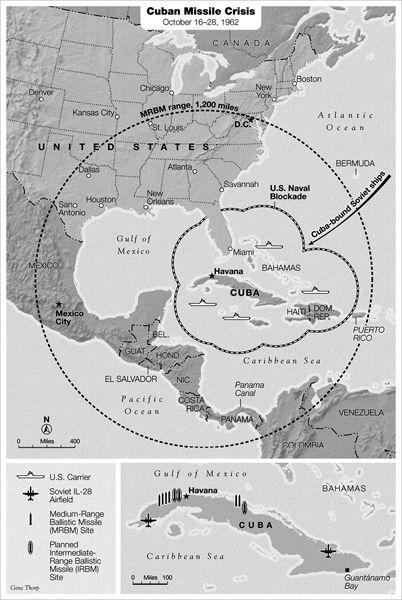

American forces around the world immediately prepare for war. All navy and marine personnel are about to have their duty tours extended indefinitely. American warships and submarines form a defensive perimeter around Cuba, preparing to stop and search the 25 Soviet ships currently sailing toward that defiant island.

U.S. Air Force bombers are already in the air around the clock. The crews will circle over European and American skies in a racetrack pattern, awaiting the “go” code to break from their flight plan and strike at the heart of the Soviet Union. The nonstop air brigade means just one thing: The United States is ready to retaliate and destroy Russia.

* * *

Thirteen hundred miles away from Washington, D.C., in Dallas, Texas, Lee Harvey Oswald is listening to Kennedy’s speech. Unlike the majority of Americans, Oswald believes that the Soviets have every right to be in Cuba. He is convinced that President Kennedy is putting the world on the brink of nuclear war by taking such an aggressive stance against the Soviets. From Oswald’s perspective, Castro’s people must be protected from the terrorist behavior of the United States.

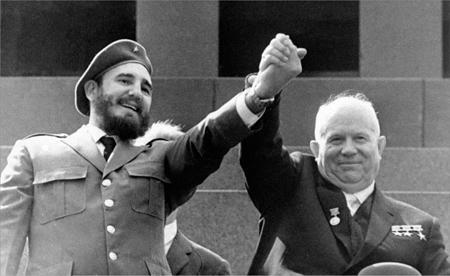

Nikita Khrushchev hoped that Fidel Castro’s Cuba would be a Soviet power base.

[© Associated Press]

Oswald moved from Forth Worth to Dallas earlier in the month and found a job at the firm of Jaggars-Chiles-Stovall, as a photographic trainee. Amazingly, the firm has a contract with the U.S. Army Map Service that involves highly classified photographs taken by the U-2 spy planes flying over Cuba. One of Marina Oswald’s Russian friends, George de Mohrenschildt, arranged for Oswald to be hired there. De Mohrenschildt is a mysterious character, a wealthy Russian-American businessman who just may have CIA connections. If the FBI, in all its zeal to stop the spread of communism, is concerned that a former Soviet defector now has a job with access to top-secret U-2 data at the peak of cold war tensions, the agency is not proving it by paying attention to his case. Nor are they curious about why George de Mohrenschildt has taken an interest in the Oswalds.

* * *

Thousands of miles away in Moscow, a furious Nikita Khrushchev composes his response to JFK’s televised message.

It was Khrushchev alone who devised the plan to place missiles in Cuba. He presented his idea to the Soviet government’s Central Committee and then to Fidel Castro just three months earlier. Khrushchev claimed the decision was a goodwill gesture to the Cuban people, in case of another Bay of Pigs–style invasion. He believed the missiles could be hidden from the United States and, even if they were discovered, that Kennedy would refuse to act.

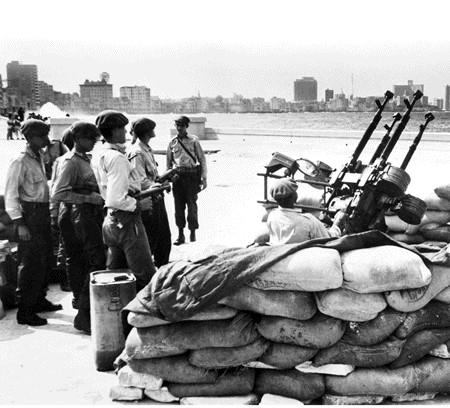

Cuban soldiers stand by anti-aircraft artillery at the Havana, Cuba, waterfront in response to the warning of an invasion by the United States.

[© Bettmann/Corbis]

But Khrushchev is wrong about Kennedy. He is surprised to learn that his adversary is deadly serious about defending his country at all costs. Khrushchev tells associates he will not back down. He is a firm believer in the old Russian saying, “Once you’re in a fight, don’t spare yourself. Give it everything you’ve got.”

On the evening of October 24, Khrushchev orders that his letter be transmitted to Kennedy. In it the Communist leader states calmly and unequivocally that the president’s proposed naval blockade is “a pirate act.” Soviet ships are being instructed to ignore it.

President Kennedy receives Premier Khrushchev’s letter just before 11:00

P.M.

on October 24. He responds less than three hours later, coolly stating that the blockade is necessary and placing all blame for the crisis on Khrushchev and the Soviets.

It’s becoming clear that Kennedy will never back down.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

OCTOBER 26, 1962

The White House

A

S THE

S

OVIET LEADERSHIP WAITS FOR

JFK

to crack, he instead goes on the offensive. The president spends Friday, October 26, planning the invasion of Cuba. No detail is too small. He requests a list of all Cuban doctors in Miami, just in case there will be a need to airlift them into Cuba. Kennedy knows where each invasion ship will assemble. All the while, the president frets that “when military hostilities first begin, those missiles will be fired at us.”

JFK is privately telling aides that it’s now a showdown between him and Khrushchev, “two men sitting on opposite sides of the world,” deciding “the end of civilization.”

It’s a staring contest. The loser is the one who blinks first.

Khrushchev spends all of that night in the Kremlin—just in case something violent transpires. The Soviet leader is uncharacteristically pensive. Something is on his mind. Shortly after midnight, he sits down and dictates a new message to President Kennedy.

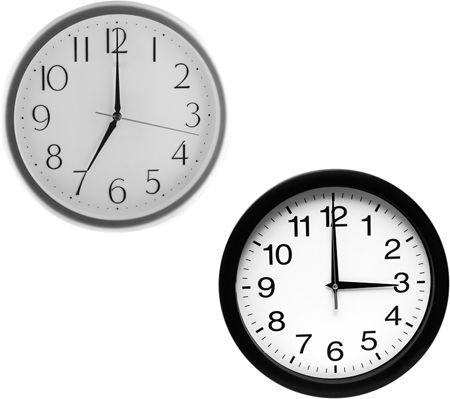

It is 7:00

P.M.

in Washington and 3:00

A.M.

in Moscow when the message is delivered. JFK has spent the day fine-tuning the upcoming invasion of Cuba. He is bone tired, running on a hidden reserve of energy.

The same is true of the ExComm—Executive Committee of the National Security Council—men who have been working with Kennedy. They’ve been awake night and day for almost two weeks. Then Khrushchev’s message arrives. The letter’s wording is personal, an appeal from one leader to another to do the right thing. The Soviet leader insists that he is not trying to incite nuclear war: “Only lunatics or suicides, who themselves want to perish and to destroy the whole world before they die, could do this,” he writes. The Soviet ruler rambles on, questioning Kennedy’s motivations.

Khrushchev closes his letter by negotiating with Kennedy in a somewhat confusing fashion. The paragraph that draws the most attention states, “If, however, you have not lost your self-control and sensibly conceive what this might lead to, then, Mr. President, we and you ought not now to pull on the ends of the rope in which you have tied the knot of war, because the more the two of us pull, the tighter that knot will be tied. And a moment may come when that knot will be tied so tight that even he who tied it will not have the strength to untie it, and then it will be necessary to cut that knot.…”

The ExComm group does not believe that Khrushchev’s message is the sign of an outright capitulation. But they all agree it’s a start.

For the first time in more than a week, Kennedy feels hopeful. Yet he does not lift the blockade. There are still nearly a dozen Soviet vessels steering directly toward the quarantine line—and these ships show no signs of turning around.

The tension increases the next afternoon, when word reaches the president that Cuban surface-to-air missiles have shot down an American U-2 spy plane. The pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson Jr., has been killed.

In retaliation, the Joint Chiefs of Staff demand that the president launch U.S. bombers in a massive air strike on Cuba within 48 hours, to be followed by an outright invasion.

President Kennedy secretly sends Bobby to meet with Soviet officials in Washington with the promise not to invade Cuba if the missiles are removed.

Then Khrushchev blinks.

The Communist leader has been so sure that Kennedy is bluffing that he has not mobilized the Soviet army to full alert. Yet Khrushchev’s intelligence reports now show that the United States is serious about invading Cuba.

The Russian dictator sees that the American president is willing to conduct a nuclear war if pushed to the limit. Yes, the United States will be gone forever. But so will the Soviet Union.

On Sunday morning, at nine o’clock, Radio Moscow tells the people of the Soviet Union that Chairman Khrushchev has saved the world from annihilation. The words are also aimed directly at JFK when the commentator states that the Soviets choose to “dismantle the arms which you described as offensive, and to crate and return them to Soviet Russia.”

After 13 exhausting days, the Cuban missile crisis is over.

* * *

In Dallas, Lee Harvey Oswald has been following the action closely. He is living alone in the new two-story brick apartment he rented on Elsbeth Street. After the couple had many fights, Marina moved in with some of her Russian friends and hasn’t even given Oswald her new address.

Outcast, misunderstood, and alone, Lee Harvey Oswald, who considers himself a great man destined to accomplish great things, festers in a quiet rage.

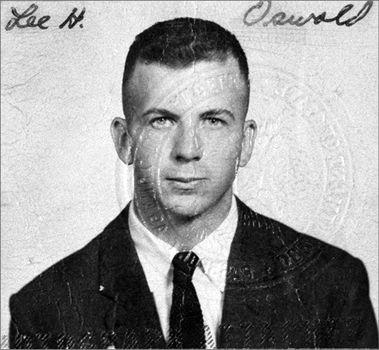

Oswald very rarely smiled for photographs.

[© Corbis]

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

JANUARY 8, 1963

Washington, D.C. 9:30

P.M.

J

ACKIE

K

ENNEDY LOOKS STUNNING

in her pink gown and dangling diamond earrings. Long white gloves come up past her elbows. She makes small talk with a man she adores, André Malraux, the 61-year-old writer who serves as the French minister of culture.

On this night, as she stands in the West Sculpture Hall of the National Gallery of Art, the first lady is truly a vision.