Kennedy's Last Days: The Assassination That Defined a Generation (7 page)

Read Kennedy's Last Days: The Assassination That Defined a Generation Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly

Three famous stars—Conway Twitty, Chubby Checker, and Dick Clark—do the Twist.

[© Bettmann/Corbis]

Teens have portable record players, small square boxes that play vinyl singles. They dance the Pony to Chubby Checker singing “Pony Time”; they think about consequences when the Shirelles sing “Will You Love Me Tomorrow?”; and they dream of dark, dangerous boys as Elvis sings “Surrender.”

Rita Moreno dances in her role as Anita in

West Side Story

.

[© CinemaPhoto/Corbis]

Communication is improving, too. Half the people in the country can dial long distance directly, without asking an operator to connect them. Although color television is a rarity, 90 percent of people in the United States own black-and-white TVs. In 1961, the first animated weekly prime-time TV show,

The Flintstones

, inspires people to go around saying “Yabba-Dabba-Doo!” Another big hit is

Mister Ed

, featuring a talking horse.

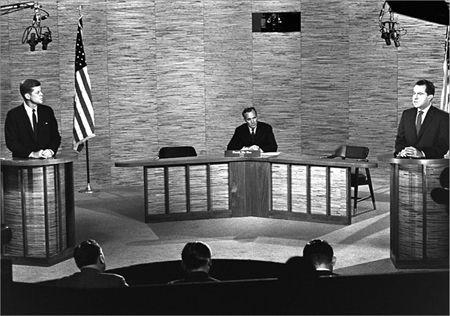

Television was a crucial factor in the election of November 1960. Presidential debates were broadcast for the first time during the campaign. People saw the young, confident John Kennedy squaring off with the seemingly anxious Richard Nixon. They chose Kennedy’s youth and passion at the polls.

The most popular names for children born in 1961 are Michael, David, and John for boys, and Mary, Lisa, and Susan for girls. Famous faces born that year include George Clooney, Meg Ryan, Michael J. Fox, Elizabeth McGovern, Eddie Murphy, and a man who someday will also sit behind the desk in the Oval Office, Barack Obama.

Televised debates offered people their first look at the candidates in face-to-face competition.

[© Corbis]

CHAPTER THREE

JANUARY 1961

Washington, D.C.

T

HE NEW PRESIDENT HAS A COCONUT SHELL

on his desk in the Oval Office. It’s now encased in plastic with a wood bottom. His staff made sure to put it in a prominent place when they moved him in. The unusual paperweight is a reminder of a now-famous incident that tested John Kennedy’s courage and made him a hero.

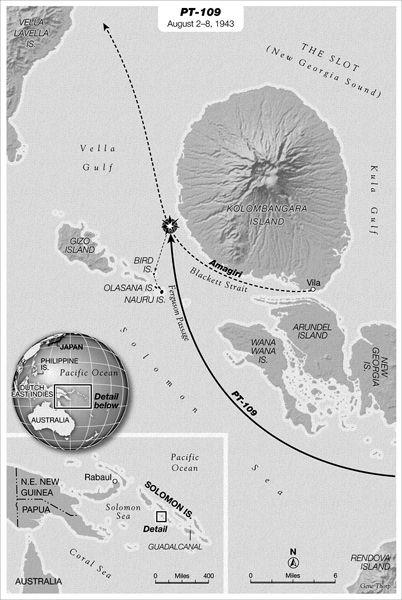

August 2, 1943

Blackett Strait, Solomon Islands

2:00

A.M.

Eighteen years earlier, in the South Pacific Ocean, three American patrol torpedo (PT) boats were cruising the Blackett Strait, hunting Japanese warships. It was 19 months since the United States had entered World War II. There were more than 50 countries involved in the war now. Since 1939, German leader Adolf Hitler had been waging his campaign of terror across Europe. In 1937, Japan had attacked China. In 1935, Italy’s Mussolini had invaded Ethiopia. These events had divided the countries of the world into two groups—the Allies, led by the United States, Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, and the Axis countries, led by Germany, Italy, and Japan. The United States had entered the war after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, a naval base in Hawaii, on December 7, 1941. By the time the conflict ended in 1945, it was the deadliest and costliest war ever fought.

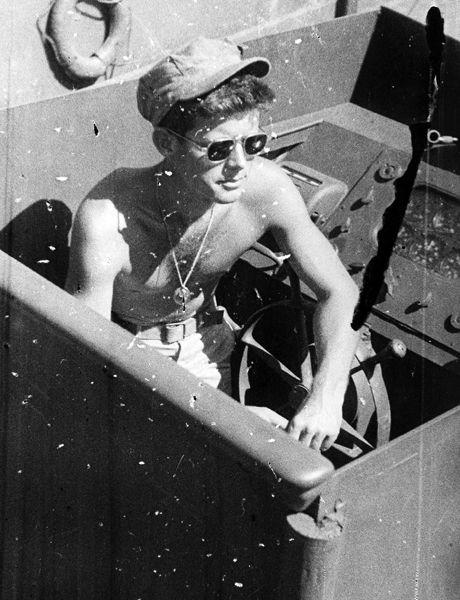

Lieutenant Kennedy on

PT-109

.

[JFK Presidential Library and Museum]

That night, one small PT boat would come close to being another casualty. At 80 feet long, with hulls of two-inch-thick mahogany and propelled by three powerful engines, these patrol boats were nimble vessels. They were capable of flitting in close to Japanese battleships and launching torpedoes. Those weapons would zoom underwater toward their targets and explode when they hit, sinking the Japanese ships.

John Fitzgerald Kennedy, the skipper of the PT boat bearing the number 109, was a twenty-six-year-old second lieutenant. He slouched in his cockpit, half-awake and half-asleep. He had shut down two of his three engines so they wouldn’t make ripples in the water that Japanese spotter planes could see. The third engine idled softly, its deep propeller shaft causing almost no movement in the water. He gazed across the black ocean, hoping to locate the two other nearby PTs. But they were invisible in the darkness—just like

PT-109.

The skipper didn’t see or hear the Japanese destroyer

Amagiri

until it was almost too late. The destroyer was part of the Tokyo Express, a bold Japanese experiment to transport troops and weapons in and out of the tactically vital Solomon Islands using ultrafast warships. The Express relied on speed and the cover of night to complete these missions.

Amagiri

had just dropped 900 soldiers on nearby Kolombangara Island and was racing back to Rabaul, New Guinea, before dawn would allow American bombers to see and destroy it. The ship was longer than a football field but only 34 feet across. This long, narrow shape allowed it to knife through the sea at an astonishing 44 miles per hour.

In the bow of

PT-109

, Ensign George “Barney” Ross was stunned when, through his binoculars, he saw the

Amagiri

just 250 yards away, bearing down on

109

at full speed. He pointed into the darkness. The skipper saw the ship and spun the wheel hard, trying to turn his boat toward the rampaging destroyer to fire his torpedoes from point-blank range—it was either that, or the Americans would be destroyed.

PT-109

couldn’t turn fast enough.

It took just a single, terrifying instant for

Amagiri

to slice through the hull of

PT-109.

The skipper was almost crushed, at that moment thinking,

This is how it feels to be killed.

Two members of the 13-man crew died instantly. Two more were injured as

PT-109

exploded and burned. The two nearby American boats,

PT-162

and

PT-169

, knew a fatal blast when they saw one and didn’t wait around to search for survivors. They gunned their engines and raced into the night, fearful that other Japanese warships were in the vicinity.

Amagiri

didn’t stop either, but sped on to Rabaul, even as the crew watched the small American craft burn in their wake.

A PT boat similar to

PT-109

skims across the water. The boats were designed to travel at high speeds.

[© Corbis]

The men of

PT-109

were on their own. Kennedy had to find a way to get his men to safety.

Later in life, when asked how that night helped him become a leader, he would shrug and say, “It was involuntary. They sank my boat.” But the sinking of

PT-109

would be the making of John F. Kennedy—not because of what had just happened, but because of what happened next.

The back end of

PT-109

was already on its way to the bottom of the ocean. The forward section of the hull remained afloat because it had watertight compartments. Kennedy gathered the surviving crew members on this section to await help. But as morning turned to noon and what was left of

PT-109

sank lower and lower into the water, remaining with the wreckage meant either certain capture by Japanese troops or death by shark attack.

John Kennedy made a plan.

“We’ll swim,” he ordered the men, pointing to a cluster of green islands three miles to the southeast. He explained that these specks of land might be distant, but they were less likely than the closer islands to be inhabited by Japanese soldiers.

The men hung on to a piece of timber, using it as a flotation device as they kicked their way to the distant islands. Kennedy, who’d been a member of the swim team at Harvard College, towed a badly burned crew member by placing a strap from the man’s life jacket between his own teeth and pulling him. It took five hours for them to reach the island, which was not much: sand and a few palm trees surrounded by a razor-sharp coral reef. From one side to the other, it was just 100 yards. But it was land. After more than 15 hours in the ocean, there was no better place to be.

They hid in the shallows as a Japanese barge passed within a few hundred yards, and then they took shelter under low-hanging trees. Addressing his men, Kennedy outlined a plan: He would get back in that water and swim to a nearby island, which was close to the Ferguson Passage, a popular route for American PT boats. He would use a lantern to signal any he saw. If Kennedy made contact, he would signal to his crew with the lantern.