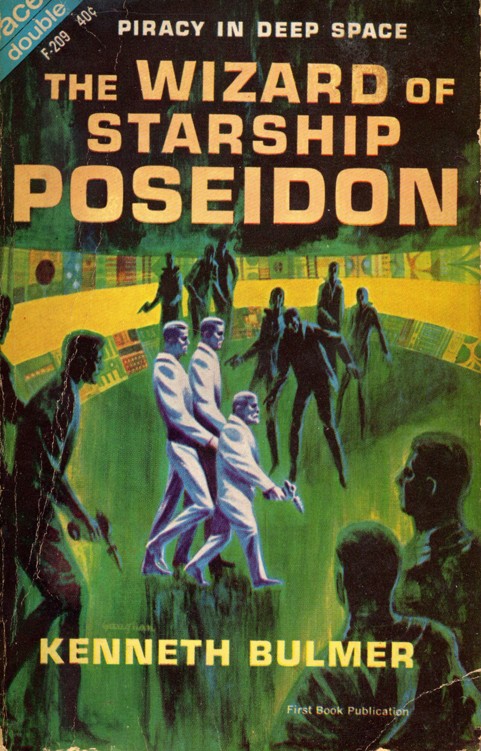

Kenneth Bulmer

Authors: The Wizard of Starship Poseiden

CONSPIRACY OF GENIUS

His height barely reached five feet, his

spindly legs supported a bulging chest, and his eyes protruded grotesquely

from a gnome-like head—but within that absurd-looking man lay the mind of a

genius.

It was a genius that had carried mankind deep

into the secrets of creation and was now on the verge of producing living

organisms from test tubes filled with inert chemicals. The world, however,

ridiculed the theories of Professor Cheslin Randolph and the government refused

to advance the millions needed for the final series of experiments.

But Professor Randolph was determined to get

the money—even if it meant turning his powerful brain to robbing a spaceship in

mid-flight, using trained viruses as his accomplices.

Turn

this

book over for second complete novel

KENNETH

BULMER

has been rated by

New Worlds

magazine as "Great Britain's hardest

working science-fiction writer." A native of London, he has produced many

novels and short stories, as well as non-fiction articles on scientific

subjects.

Buhner

states that he has been reading and writing science-fiction for longer than he

cares to remember, starting both while still at school in the early 1920's.

During the war he served with the Royal Corps of Signals and published and

edited a Service magazine in Africa, Sicily and Italy. It was while basking in

the Italian sunshine that he first heard of an atomic bomb having been

detonated over Japan—and thought it was just another hoax of his comrades.

He

is an active member of London "fan" circles, but also includes among

his hobbies model ship construction, motor racing and the study of the

Napoleonic legend.

THE

WIZARD

OF STARSHIP

POSEIDON

by

KENNETH

BULMER

ACE BOOKS, INC. 1120 Avenue of the Americas

New York 36, N.Y.

the

wizard

of

stabshtp

poseidon

Copyright

©, 1963, by Ace Books, Inc. All Rights Reserved

Ace

Books

by

Kenneth

Bulmer

include'.

THE

SECRET OF ZI (D-331) THE CHANGELING WORLDS (D-369) THE EARTH GODS ARE COMING

(D-453) BEYOND THE SILVER SKY (D-507) NO MAN'S WORLD (F-104)

LET THE SPACEMEN BEWAB

e

I

Copyright

©, 1963, by Ace Books, Inc.

Printed in U.S.A.

CHAPTER ONE

A™

^ - ^ „

ceeding

attack with merciless and sacrificial ruthlessness, Black Queen scissored

across the board in the final onslaught like a teeth-heavy monster of the

deeps. White's black bishop crumpled, was removed. White's king's rook, engulfed,

was laid back in the box. The white king, at bay, surrounded and under heavy

fire, covered by a lone and pitiable pawn, surrendered unconditionally.

"Mate,"

said Professor Cheslin Randolph, and turned away from the chess table, picked

up the latest copy of

Nature

and and leafed through the slick pages.

"Have you seen Kishimura's letter? He claims to have synthesised

poly-amino acids using Matsuoka's nought-nine-seven technique. Oh,

I

know he's using a whole primitive planet as a laboratory under

stringently sterile conditions, just as I shall on Pochalin Nine; but—"

Professor

Randolph stopped speaking, lifting his gnome's head to return his guest's deep

and half-amused stare.

"You're

an amazing man, Cheslin," said Dudley Har-court, Vice-Chancellor.

"Your mind has just grappled with the utmost concentration on a complex

chess situation, yet you turn away the second the game is over and just as intensely

concentrate on a fresh subject."

"Chess

is just a game. Speed, decision, attack—to win is not very clever. And it grows

less amusing week by week. I'm chafing to space out to Pochalin Nine."

The two men sat comfortably ensconced under

discreet lighting in Randolph's chambers. About them the unseen but omnipresent

breath of the University pulsed beyond the glass and porcelain walls. The

decanter and tobacco jars caught vagrant gleams of light as the men moved. The

chambers were furnished with meticulous taste, heavy, authoritative, somehow

mechanical, completely lacking any feminine grace.

"Are

you over-working, Cheslin?" The Vice Chancellor spoke with the brutal

frankness he reserved for friends. "Your own work devours you. Why not

give it a rest—for a little time. Take a long holiday."

Professor

Randolph dropped the copy of

Nature.

He

selected a cigar and, uncharacteristically, sniffed it, looking up with his

frog's-eyes over the rolled leaves at the Vice Chancellor. Randolph stood five

feet in his socks, and his chest measurement was proportionate; only his head

appeared in normal proportion to a grown man's—and that appearance was

deceptive.

"Vice

Chancellor," he now said with precise meaning. "You invite yourself

for our friendly contest over the chess board. I accept because for an hour I

can spare the time from my laboratory. But then you suggest: one, that I rest

for a little time, and, two, that I take a long vacation." Randolph's

smile transferred the image of his Black Queen to his own creased face.

"What is it you have to say to me?"

As

he had on the chess board, the Vice Chancellor crumpled under the directness of

the attack.

Dudley

Harcourt, as Vice Chancellor, had grown wearily resigned to swinging to the

winds of desires in the University. Like some moss-encrusted weathercock, he

merely pointed up the trend of events. When he exercised his own discretion, he

did so deviously, through third parties. He had been unable to find anyone

willing to risk the barrage of fire from tiny Professor Cneslin Randolph. So,

here he was himself, uncomfortably mustering his own arsenal of weapons to

combat this frightening gnome.

Harcourt

had not been bom on Earth. His outward face to the Galaxy was the usual tough,

cynical, relaxed countenance of the star colonial, very much a stock figure,

and an expected one. Over that he had carefully laid the shining veneer of

academic distinction so that, at this point in his career, he was Vice

Chancellor of Lewistead and not too unhappy with progress so far.

Unfortunately, Professor Cheslin Randolph, occupying the chair of

extraterrestrial micro-biology, posed the type of problem best represented by a

nine-inch crowbar between the spokes of a turning wheel.

Unused

to prolonged delay in response to a question-even from backward

students—Professor Randolph took the cigar from his mouth and said, "Well,

Dudley?"

Harcourt

lifted both hands and let them fall, softly, onto his knees. He did not look at

Randolph.

"It's the Maxwell

Fund."

"You

mean there's a hold up? I thought everything had been settled—more

negotiations? What now?"

"As

I said to the Trustees. Unfortunately, this year there very well may be—further

negotiations."

Randolph

sat forward, hunched in his own special chair. His tiny feet stamped

impatiently on his footstool. His creased, wide face with its angry frog's-eyes

might, in a lesser man, have been merely ludicrous. When Professor Randolph

puffed up his face, turned down the comers of his mouth, suddenly and with

devastating effect slitted those protruding eyes, he became even to the Vice

Chancellor of Lewistead a formidable and daunting figure.

When

he spoke the habitual rasp had left his voice; he purred like a cat with a

mouse.

"Is

there to be more delay with the Maxwell Fund? This is my year for it. I've

waited ten years for this. All my work is arranged, the Extraterrestrial Bureau

has granted me Pochalin Nine, I've taken on Doctor Howland as chief

assistant—everything for the last decade has been built up ready for this

coming year. You know that. The whole establishment knows it. With the

equipment I'm buying with the Maxwell Fund I shall initiate a series of

experiments on Pochalin Nine culminating in—life!"

He leaned back, and his thoughts now were

gripped by the

obsession of his life's work.

,

"I

am absolutely convinced, despite certain scoffers, that I can create artificial

life—of a rudimentary type, naturally. And to do that I need equipment and

funds far beyond the normal college allowance. Old Maxwell with his Nuclear

Weapons and his conscience created the Maxwell Fund— I've waited ten years. Ten

years!" His cramped face radiated the tenseness which even a minor

obstacle could create these days. "I'm opening up the future, Dudley!

Don't hold me back now!"

The glass and porcelain walls filtered the

ribald sounds of students; in the all electric rooms not even the ticking of a

clock could serve to abate the ominous silence.

At

last: "Well, Dudley? This is my year for the Fund. What is your

problem?"

"Cast

your mind back a moment, Cheslin. Last year the Fund went to Gackenbach of

Managerial Ratio-analysis. Year before to Mesarovic for Wave Mechanics. Year

before that to Lewis for Endocrinology. Before that—ah—"

"Physics

or Nucleonics, I expect. But what of it? That's what the Fund is designed for.

And my whole department is geared for the new equipment—we're hungry for

it."

Randolph

had refused to read into the Vice Chancellor's attitude any menace of serious

threat—the Fund was his all right—but something was bothering Harcourt "If

there is a delay my whole department would suffer. Doctor Howland is a great asset;

but he's only here on the strength of the new work. All my work would be wasted

if— My results cannot be published until they have been shown to be so. I'm

convinced I can do what I claim, even if people like Kawaguchi scoff. But we

cannot wait too long for the Fundi"

"As

you know, Cheslin, the Fund has been scheduled for a considerable number of

years into the future. We have to look very carefully at the relative degrees

of importance—"

"I must have the

Fund—this year. It's mine!"

"Nothing has ever been

officially agreed—"

"Officially!" Something very like

panic touched Randolph now; an emotion he could not at first recognize. His

calm scientific manner began to fray under the ruthless ambition that was his

chief characteristic, and the dominance of his personality sought blindly for a

concrete target to smash and destroy. Nothing was going to stand in the way of

his life's work—

nothing!

"I'm very sorry, Cheslin." Vice

Chancellor Harcourt spoke stiffly, finding the words red-hot in his mouth.

"You must by now have realized that there has been

a

change in plan for the Maxwell Fund."

"No! I don't believe it! They—the

Trustees—you, you wouldn't take the fund away now. . . ."

"It's not a question of taking away the

Fund, Cheslin. No firm decision had been reached on its disbursement this

year."

"But it was to come to me. That had been

agreed as 'long ago as ten years. . .

"No, Cheslin." Slowly Harcourt

shook his head. "Not so. Nothing was said, nothing was written—"

"But it was implied! The Chancellor

himself told me the fund would be mine this year."

"If that is so,

Cheslin, the Chancellor has no memory of it"

"No memoryl"

Randolph's

tiny hand groped for the arm of his chair, gripped and clutched as though

seeking the feel of

a

solid object in an ocean of madness. "No

memory . .."

"I

can only say I am sorry. We've been good griends, Cheslin. I rather hope that

will not be altered by all this, this unfortunate development." Harcourt

stared at the little man hunched in the deep armchair. Hesitatingly, he went

on, "Quite off the record, I will say that my loyalty to the Chancellor

and the Trustees has been seriously strained over this decision. There was talk

of

a

resignation-mine. But you can't fight all the

deadweight of authority, Cheslin. The men with the power see they keep the

power— and to hell with anyone else."

"Power," said

Randolph, softly.

Harcourt felt profound unease. He had never

before seen the little Professor so crushed, so woeful, so shattered. And that

reaction surprised him. He had expected anger, indignation, righteous wrath.

Those Randolph had displayed; but he had gone through them at dizzy speed to

end up like this—beaten.

"Tell

me, Dudley. What is to happen to the Fund this year?"

"Those people who have received the Fund

over the past ten or eleven years. They have one thing in common."

"They've all been lucky."

Harcourt shook his head. "No. They're

all of the Sciences. The Maxwell Fund was designed for the use of the faculty

as a whole."

"Am

I, then, no longer a member of the faculty?" Harcourt ignored that, went

doggedly on. "This year the Maxwell Fund is going to Professor Helen

Chase~" "The glamorous female with the titian hair?"

"Yes."

"I've

never really understood what it is she does.* "She holds the chair of

Shavian Literature—" "The what?"

"Chair of Shavian Literature."

Professor

Randolph had to make a conscious effort to remember just what that was. He had

to bring his mind away from the universe of science, back to a world and a

galaxy around

him

that he took for granted and never thought about from

one decade to the next.

"Does

that mean she's a member of the weirdies? Those odd people who creep about

muttering outlandish tongues, dead these thousand years, who don't know a

parsec from an electron volt?"

"The Humanities, my

dear Cheslin. The Arts."

"And

they're the infestation stealing the Fund from me.

...

This is a mockery! What do they need the Fund for?"

"The

University badly needs a new tri-di live theatre— we have rather a good name in

the Galaxy for our work there, you know."

"Why can't they watch television like

everyone else?"

Harcourt

smiled sadly. "That's commercial. Here we are dealing with Art—with an

oversize capital 'A'."

Randolph began to comprehend the magnitude of

the calamity that had wrecked him. He pointed with a narrow finger. "A

theatre of however exotic a design can't cost all that much. My equipment,

travel and transportation costs to Pochalin Nine—that's a perfect planet for

the workl Primitive, absolutely sterile, not a single living cell on

planet—living expenses there, everything will absorb every last penny of the

Fund. But I would stand to deduct the cost of a measly theatre.

..

."

"No good-"

"Oh, I can see the reasoning. Spend the

Fund here, right in the University, have something here and now to show for

it."

"It's

not only the theatre. Helen Chase has the opportunity of buying for the

University a most wonderful collection of Shavian manuscripts, marginalia,

trivia, and, also, a number of documents in dispute."

"Dispute.

I like the sound of that." Randolph's words carried a bitterness that cut

Harcourt.

"Professor

Chase is working to prove her theory that George Bernard Shaw and Herbert

George Wells were one and the same man. One was the pseudonym for the other. If

she can prove that Wells was a pseudonym used by Shaw then she, as a Shavian,

will throw the Wellsians into utter confusion. It will be a greater triumph

than merely proving, as many have tried, that either Wells wrote Shaw's work,

or Shaw wrote Wells'."

Exasperated beyond reasonable control,

Randolph pushed his little legs down into the soft carpeting, stood up, and

began pacing agitatedly and threateningly about the room.

"But

who cares?" he demanded with a vicious swish of a tiny hand. "These

men—or man—have been dead for thousands of years. They belong, as I remember,

to the Dark Ages. They probably didn't even have typewriters or ball points to

work with. What, did they chip these master-works out of stone?"

"I'm

sorry, Cheslin." Harcourt, too, stood up. With his usual tact he did not

stand too close to the little man. Al-thought, come to think of it, the

aggressive power of Randolph usually obliterated his small stature from the

memories of acquaintances. "Damned sorry." He'd had about as much as

he could take. Killing a man's life work was not sport for which he cared.

"I'd better be getting along. You'll-"