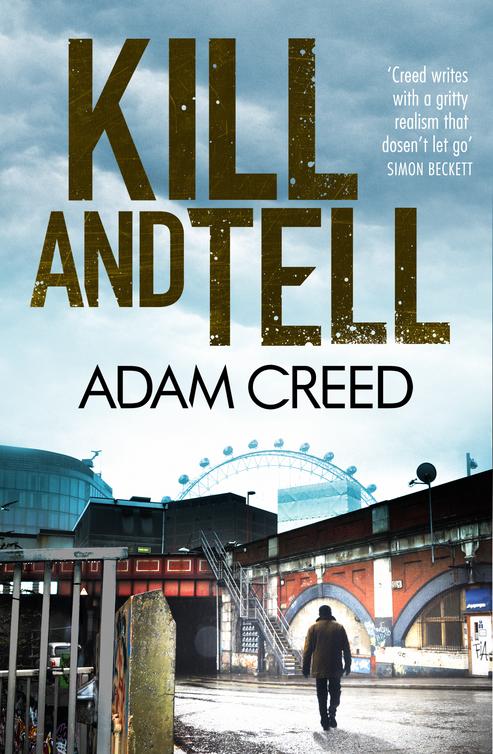

Kill and Tell

Authors: Adam Creed

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Mystery, #Crime Fiction

A DI STAFFE INVESTIGATION

ADAM CREED

For

Mary Ruth Creer

1930–2012

Carmelo looks at the gap his missing finger has left between his wrinkled wedding and index fingers. The finger has been missing since he was a very young man and its absence reminds him of his shame.

He holds the child tight and the baby nestles its warm head in the folds of Carmelo’s old neck, and he strokes the back of the child’s downy skull with his three fingers.

Carmelo has learned to live without the things he lacks, and in moments like these he thanks God for the life he has been gifted. He says ‘Sorry’ for his part in not being able to love his own son. He could have been around more, but those were the busiest years: London and Brighton, sometimes Sicily. In fact, when his only son Attilio was six months old, the same age as baby Gustav here, Carmelo left poor Attilio with his manservant, Jacobo, for three whole months. Jacobo suffered the infant screaming the night sky to shreds. The baby had killed his mother, as his first act in the world. Maybe that has something to do with it.

Baby Gustav coos and shifts himself deeper into Carmelo’s neck. Carmelo comes once a week and the baby’s mother, Vanya, always marvels at how Carmelo can lull the child into sleep. ‘You’re a marvel, Carmelo,’ says Vanya, coming across and passing her arm through his, wishing she had a father like Carmelo.

But all Carmelo can think is, ‘Today will be the day they come. This is the day when it is all reckoned. I have to act.’ He has felt this before, but never with such gravity. His breath shortens and he coughs, dry. He hands the baby to Vanya and coughs again and again into his handkerchief.

Vanya lays baby Gustav down in the cot Carmelo bought, in the corner of the three-room apartment that Carmelo pays for. And the husband, Bogdan, watches all this with a sour look on his face. He swallows the last morsel of his pride as he says nothing when Carmelo presses a roll of twenties into Vanya’s hand; nor as she kisses Carmelo and thanks him, saying shouldn’t he see a doctor?

Bogdan puts half the money in the jar for Poland. Later, he will sleep unsoundly and in the dead of night he will rise to work the night shift that Carmelo found for him. Carmelo says he knows what it is like for immigrants. He was one once.

Carmelo had seen Vanya cleaning in the casino of one of his friends when she was six months pregnant. He had slipped her a hundred and told her to go straight home and rest, and that he would call on her at home and fix up her husband with a decent job. A mother should be a mother, he had said.

A week after he first found her, Carmelo called on Vanya. She was coiled on the sofa, her tears all run dry. She had just been to the hospital for the final scan and her voice croaked as she told Carmelo that the doctor said the baby had a bad heart and he really needed ultrasound to have any chance of survival but they couldn’t have it on the National Health. The doctor said the baby’s heart weighed the same as a twenty-pound note, as opposed to hers which was the weight of a pound of pork. ‘A pound of anything,’ Carmelo had said, comforting her, saying he would make everything all right, sending the baby, inside its mother, to Milan, where they scanned him some more and opened his valves.

When baby Gustav was born, his heart worked just fine, and now it seems he will have a mainly healthy life. Carmelo knows the value of good medicine, and timely interventions.

He dons his hat and Vanya helps him on with his coat. Carmelo wears a winter Crombie all year long. He likes the weight of it, can’t bear to be cold. She pats his shoulders and straightens the sleeves as Carmelo and Bogdan exchange a look. Carmelo wishes Bogdan wouldn’t regard him so. He once told Bogdan, ‘It is a gift, to accept kindness without flinching.’ Bogdan had shrugged, said nothing, but wondered if one day or night he might have to do something for Carmelo: proof that these favours are not kindnesses, but prepayments.

Today, Bogdan rises from his chair and tells his wife he is going to get black bread and some stamps for Poland. He leaves the flat at the same time as Carmelo and as the old man gets his keys out for the Daimler, Bogdan says, ‘I just want to say thank you, Mister Trapani. Thank you for everything you do for my wife and the baby. I hope I can be more like you some day.’

‘You wouldn’t want that, my friend. You’re better the way you are.’

‘That’s easy for you to say.’

The men look at each other. Eventually, Carmelo says, ‘We’ll be even, when all is done. Have no doubt.’

‘Is there something I will have to do for you? If so, I would like to know. It makes me afraid.’

‘What makes you think like that?’ Carmelo bites his bottom lip, as if he was in pain. ‘Fear can be our friend. In Sicily, my grandfather was a fisherman and he used to tell me, “Carmelo, you must be afraid of the sea. It will kill you if you are not afraid.” But that sea gave my grandfather a livelihood. It brought him joy and food and friendships. Without the sea, he would have been dead.’

‘Did it kill him in the end?’

‘Oh no. He made an enemy. He was a proud man, my grandfather, and that killed him, not the simple matter of going to sea.’ Carmelo watches Bogdan put his helmet on, kick the moped off its stand. He says, ‘You must do whatever it takes to make your baby’s life complete, even if one day you will have to harm him.’

Bogdan sits astride his moped, puzzled. He watches Carmelo get into his Daimler, manoeuvring into the traffic on Cambridge Heath Road.

Carmelo sits at the lights and looks back at Bogdan, who raises a thumb at him, as if he might have got the point. The lights go green and Carmelo moves away, Bogdan still on his moped outside his flat. Carmelo likes to drive. He does it slowly and cautiously with Radio Three murmuring just above the sound of the engine, like sea and breeze.

Today – though there is nothing in his rear-view mirror or his side mirrors to prove it – Carmelo is sure he is being watched and as the traffic peters away on the short drive to his house, he constantly checks his mirrors. Eyes are on him, and his time is come. He wonders if there might possibly be no such thing as hell.

When he gets to the gates of his mansion, which he remodelled after the war, here in the loveliest secret corner of the City, Carmelo presses the button on his remote control. The gates glide inward, to his private world. He takes time to smile up at the CCTV camera then looks in his mirrors a last time, before going through. He can see nobody and he drives the car cautiously into the garage, belatedly pressing for the gates to close. Sometimes he forgets.

He lets himself in the front door and calls ‘Jacobo!’ but there is no reply, so he telephones Goldman himself. The preparations are complete. He is almost there. He breathes in as deep as he can, feels his heart flutter. He calls the policeman and waits, is told that the Chief Inspector is in an important meeting. ‘Do you want to leave a message?’ the man says.

‘No. This also is important. Of the very highest importance.’

*

Staffe heaves the parcel onto the scales and the anxious postmistress tells him it will be fifty-six pounds. She has big eyes and almost no lips at all. The way she looks at him, he thinks she can’t tell that he’s actually worth a few bob. ‘Is it of value?’ she says.

‘It cost less than the stamps!’ he laughs. ‘It’s only piccalilli I made myself. Is that allowed? To post abroad, I mean.’

‘You shouldn’t have said.’

‘My sister lives in the middle of nowhere. In the Spanish middle of nowhere. She misses home.’

‘Who taught you to make the piccalilli?’

Staffe feels sad for an instant, then glowingly happy. ‘My mother.’

‘And she didn’t teach your sister?’

‘We’re very different.’

‘You must love her very much.’

Staffe wonders whether the postmistress refers to his mother or his sister. He gives her three twenties and looks at his watch, sees he is already late and says, ‘Put the change in the charity box.’

He walks up the Caledonian Road, which disappears at the cusp of a small rise, just the blue of sky beyond, between the low rows of shops and flats and the occasional office block – and the prison, skulking like an angry Victorian giant.

Later, he will go into Leadengate, to trawl through all the interviews his sergeant, DS Pulford, ever conducted with any member of the e.gang, and to document all the calls his sergeant made, from home, mobile and the office, going back through all the months between when Staffe was shot and his shooter, Jadus Golding, was murdered. That was just three weeks ago and his sergeant is remanded on bail for it. Suspect number one.

A part of him wishes he could amble on, towards the sky at the end of the street, but he knows what he must do and he churns the questions he must ask Pulford. As he does it – as if he is being whispered to, from across a Spanish desert – he touches his chest, where his scars are almost healed.

The meat wagons queue outside the electronic gates of the jail, bringing fresh. Twenty yards away, the loved ones wait for their visits. The women are young, but their faces are already hard and their children cling on, perching on hips, or tugging at the shortest imaginable skirts. Staffe goes up to the window, past the queue and shows the officer his warrant card, telling him the purpose of his visit.

‘You’ve just walked past the queue, now get to the back,’ says the PO, smirking, swivelling on his seat and saying something to his colleague behind the grille that makes them both laugh – at Staffe’s expense.

*

DS Pulford is led into the visitor centre by a sneering PO who takes delight in confiscating the sergeant’s clutch of books and folders. ‘Bit fuckin’ old for school, aren’t you?’ he says.

Pulford puts a brave face on it, sits opposite Staffe and says, ‘I came straight from the library. I only get to go once a week. Today, they had what I was after, but the choice isn’t good.’

‘What are you up to, David?’ says Staffe.

‘I’m studying for an MA.’

‘I mean with these damned charges. There’s talk of this having to go to trial if we don’t come up with some evidence soon.’

‘I’ve got a supervisor at UCL – one of the most eminent criminologists—’

‘For God’s sake! You need to focus.’

‘That’s precisely what I’m doing.’

‘You didn’t kill Jadus Golding,’ says Staffe.

‘Is that a question?’ says Pulford.

‘It would be good to hear you say it.’

‘Do I need to?’

‘Unless we can come up with some evidence, you will have to say it to a jury.’

‘You’re not a jury.’

‘Say it.’

‘I didn’t do it.’ Pulford says it the way a teenage boy might goad a parent.

‘Christ, Pulford! This isn’t a game.’ Staffe sees that his sergeant’s mouth is weak. Pulford breathes deep, shakes his head as if he is shivering. ‘Are they looking after you?’

‘Some of the POs are all right, but I’m a copper.’ He nods at the PO who brought him in. ‘That’s Crawshaw. He’s a bit of a twat.’

‘Have they got you in isolation?’

‘When I first came in, but I don’t want that. It makes them think you’ve something to be afraid of.’

‘And have you? There’s two members of the e.gang in here. Did you know?’

Pulford gives Staffe a withering look. ‘I know all right.’ Jadus Golding, of whose murder the DS stands accused, was a member of the e.gang.

‘Christ, Pulford. Is there

anything

you’ve not told us?’

Pulford looks away.

‘There is! It could get you out of here.’

‘I’ve told you everything I can, sir. And that’s the truth.’

‘How can the truth hurt you – if you’re innocent?’

‘Sometimes, on the Force, you only see half the story. It’s the perspective we have. Do you see that?’

‘Tell me what you’re afraid of, Pulford.’

Pulford says nothing. His eyes say, ‘Plenty.’

‘There’s a number you kept calling from your mobile. It’s unidentifiable, but I called it the other day and we got a trig on it before they could turn it off. It was somewhere on the Attlee.’

‘Sylvie wrote to me.’

‘She always liked you.’

‘Is there a chance the two of you might . . . you know?’

‘We’re through,’ says Staffe, feeling peculiar at hearing Sylvie’s name. The first time in a long time. ‘Now, who were you phoning on the Attlee? These calls were all made at times you weren’t on duty.’

‘She wrote some kind things, but I think she found it upsetting. Maybe you could tell her not to write again.’

‘I told you, that’s all over. Stop changing the subject.’

‘Maybe you should call her.’

‘Just tell me who the fuck you were calling!’

‘If I could, I would.’

‘At least explain why you can’t tell me.’

‘There is something you can do.’

‘Tell me.’

Pulford hands him a piece of paper. ‘Can you download me this article? They don’t let us access the Internet.’

‘My God! How long are you planning on being in here?’