Kinglake-350 (13 page)

Authors: Adrian Hyland

None of these reactions, it should be remembered, are signs of moral failing: of cowardice, incompetence or irresponsibility. They are genetically programmed automatic responses to an abnormal situation that need to be understood if we are to improve our responses in the future.

Nevertheless it is true that while some people curl up and die, others automatically swing into action. Why? Genetics has a lot to do with it. Research into animal behaviour has found that the tendency to paralysis, for example, is passed on to offspring.

But in our own species the most effective response is based upon a solid foundation of preparation, training and experience. The more familiar the situation, the less chance of the brain shutting down or succumbing to the more extreme manifestations of stress. That is why firefighters practise such basic skills as bowling out hoses and operating pumps until their arms ache; they need those procedures to become ingrained, automatic. That is why every family in the bushfire zones should practise fire drills until the kids are screaming with boredom.

Police officers like Roger Wood and Cameron Caine had the kind of training and experience that made them less likely to go into panic mode or develop tunnel vision. One of the firefighters who encountered Wood at a critical moment later that night was struck by the way in which he seemed to be able simultaneously to maintain a conversation, issue instructions, make decisions and monitor the wellbeing of the people around him.

Obviously the better the training, the more effective it will be, but it need not be formal or organised. A ten-year-old English schoolgirl named Tilly Smith was on a beach in Thailand in 2004 when suddenly the tide ran out and the water began to bubble strangely. The beach was full of tourists standing around staring at the phenomenon, but Tilly’s class had seen a video about tsunamis two weeks before and she recognised the signs. She alerted her parents, who organised a frantic evacuation of the beach minutes before the wave struck. It turned out to be one of the few in the area on which nobody was killed.

Another important element is leadership, particularly when those affected by the disaster have clustered, as they tend to do. Coming together for mutual support is a natural instinct. On September 11, 70 percent of the survivors discussed the situation with the people around them before taking any action. After the 2005 London transit bombings some victims refused to leave the Undergound, so reluctant were they to abandon the groups they’d formed.

Again, Black Saturday has its parallels. One survivor said that she was terrified to leave the truck that had rescued her, so desperate was she to remain with the group.

‘What you actually look for in these circumstances is someone who can tell you what to do,’ said Ian, a victim of the London tube bombings. ‘Even if it’s just a basic “Stay here” or “Move there”, you just need guidance, because you are a bit all over the place, as you can imagine.’ For Ian, badly injured, the most comforting thing he heard was the voice of the driver telling him to make his way out of the tunnel.

If individuals or groups demonstrate any of the negative responses outlined above—paralysis, tunnel vision, indecision—their best hope is that somebody will stand up and take control. They need people with training and experience, who have been taught to assess risks, to judge the best course of action, encourage others to follow. Massad Ayob, a veteran police officer and trainer commented: ‘The single strongest weapon is a mental plan of what you’ll do in a certain crisis. And an absolute commitment to do it, by god, if the crisis comes to pass.’

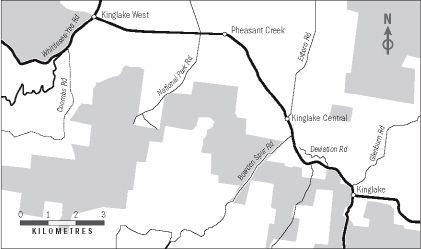

Leadership. Experience. Judgment. A commitment to a plan. When the two police officers came together at Pheasant Creek, the crowd had a pair of leaders who ticked those boxes.

Months after the fire their senior officer, Acting Senior Sergeant Jon Ellks, was to comment: ‘Those two, they’re smart and they’re sensible, both of them. Good coppers. If it hadn’t been for them, a lot more people would have died that day…They had a plan. Even if they didn’t know it, even if it was formulated in a moment, on the run. Even if they had to bend the rules. They knew their community backwards, they knew the options. All that knowledge and experience came together. They had a plan.’

Roger Wood is happy to see Cameron Caine coming towards him. When he gets close enough for speech, though, Cam’s beside himself.

‘Woody, I can’t find Laura and the boys.’ He’s been trying to call his wife, without success. Have they tried to get through, been overwhelmed on the road? Have they even left home? Are they trapped back there?

One of Cameron’s neighbours rolls up: she only just made it out, drove through a wall of flames. No, she hasn’t seen Laura.

Wood puts a hand on his colleague’s shoulder. ‘Mate, we can’t do anything about that right now. The fire’s about to hit. We have to get these people out of here.’

Just at that moment the Caine family car comes racing out of the smoke, the shaken family on board. Cameron rushes over to embrace them, relief telegraphed in his every gesture.

The two officers reconvene to canvass their options. People gather round, hoping for answers. If anybody has any idea of what’s going on, surely it will be them.

If only, Wood breathes to himself. He feels the burden of responsibility pressing down across his shoulders.

The distant roar gives an added urgency to the exchange. The fire is closing fast. The crowd is growing thicker by the second, the tension mounting. They can’t stay here.

As police officers, they have no authority to evacuate members of the public, but this is not a day for following regulations. It’s a day for a good copper to follow his instincts and take the initiative.

But where the hell can they go?

The CFA at Kinglake West was the best option half an hour ago, but is it still safe now? Fires are breaking out everywhere, as far as they can see.

The roar of the fire is a heavy bass thud now, rattling the windows. Embers fall around them. That terrible darkness is descending again. They have no choice.

‘CFA’s our only option,’ says Wood. ‘I’ll go on ahead, check the coast is clear. Give you a call.’ That makes sense: he has the car. ‘If I can’t get through, I’ll come back.’

Cameron will stay behind, shepherd the crowd out when Wood confirms it’s safe.

Wood drives off. Cameron stands in the gravel, fear building in the back of his mind. Time passes; the roar grows louder. Visibility diminishes. Darkness. The fire is almost on them. Where the hell is Woody? The first flashes of orange begin to crackle among the pine trees.

The phone rings. His hands trembles as he answers it.

‘Cam.’

Woody. Thank christ.

‘Send ’em down. Fast. Road’s clear; won’t be for long.’

Caine doesn’t need any more prompting. He runs through the crowd, waving his arms and screaming: ‘Get on down to the CFA! Kinglake West!’

His own family move out. Others join them. The trickle becomes a flood, but he shakes his head in frustration at how slow it is. Don’t they have any idea what’s coming? People are dying out there; he can sense it. He doesn’t want to join them. He doesn’t want any of the crowd from Pheasant Creek—this haphazard mob who’ve suddenly come under his care—to join them, either. There are mothers and babies in those cars, old people, little kids, their eyes up against the window staring at him as they roll past. Some of them are neighbours and friends.

A bloke in a twin-cab towing a trailer is facing the wrong way, takes an eternity to turn around and join the convoy, blocking other people off in the meantime.

‘You!’ Cam roars. ‘You’re holding everybody up!’

The driver doesn’t hear, or doesn’t want to.

The smoke pouring out of the pine plantation is growing thicker by the second. The roar is tremendous. He’s having trouble breathing now, smoke filling his lungs, biting at his eyes. Visibility is going.

The twin-cab finally completes its snail-paced turn, rattles off down the road. Others follow. He runs among them, slapping roofs and tailgates, yelling, ‘Go, go! Move!’

Still it takes forever. Does time stand still in a crisis? He can feel the radiant heat now. He spots flames flickering through the treetops. He shelters behind a bus stop, keeps yelling, trying to kick a bit of urgency into the stragglers. Christ, how many of them are there? Why is it all taking so long? Is he going to burn to death here at Pheasant bloody Creek? More cars come drifting in through the smoke. He waves them on.

At last, there’s only one vehicle left. A white van. He runs across to catch a ride, stares at the occupant. The driver is one of Kinglake’s recalcitrants—‘known’ to the police. They arrested him only last week.

‘Give us a lift out of here, mate?’

The door flies open. ‘Jump in.’

As they bolt out of Pheasant Creek, a terrifying sight looms in the rear window: the bus shelter he was standing in seconds ago is engulfed in flames. A vast wave of fire roars out of the pine plantation, swallowing the store. The explosions begin, the first of hundreds he is to hear this night: bottles and cans burst through the windows. The gas tank out the back goes up in a sheet of blue flame. He’s made it out by the skin of his teeth, by the hairs on the back of his hand.

Maybe. The inferno is throwing out jets of flame, igniting the bush alongside the road, and Caine has the eerie feeling this damned fire is seeking him out, hunting him down. He and his driver find themselves white-knuckle racing through a tunnel of fire. And finally coming out of it.

At last the Kinglake West CFA appears through the windscreen, and Cameron is relieved to spot the familiar figure of Roger Wood out on the road, directing the cars out onto the adjoining oval, making sure nobody panics and heads down the deadly Whittlesea track. He gets out to lend a hand.

The fire can’t be far behind. The CFA brigade members are working furiously, hosing the building down, spreading foam, doing their best to make it safe.

A later count showed that there were more than two hundred people sheltering at the CFA at Kinglake West. Vehicles of every description, trailers and trail bikes, horse floats, a horde of four-wheel-drives and panel vans, a mini-bus.

The atmosphere is quiet but tense. People are crying, passing round bottles of water. Some are punching frantic thumbs at mobile phones, mostly without success. Telecommunication is random at best, hopelessly choked, deteriorating progressively as the transmission towers fall.

There are people in the crowd who already know they’ve lost their homes. Many are rigid with fear for family and friends they’ve left behind. Kids are fretting about pets, although there is a menagerie of them here: cats and dogs, birds, horses, goats. The smoke is growing thicker by the minute. People are spluttering and gasping, passing round smoke masks, pulling shirts over heads. Some are in shock, dazed, their faces blank.

The two policemen assist stragglers, deal with the odd desperate individual wanting to make a run for it. One old man in a ute nearly mows Cameron down in his determination to get away. Cam has little choice but to leap to one side and watch the bloke go rattling off into the smoke.

Wood makes another attempt to reach his own family, again without success. He feels a quiet despair biting at his heart. Tells himself there’s nothing to be gained by thinking about it.

Wood and Cameron mainly stay outside, two tall men silhouetted against a horizon on fire. How can this be happening? Wood asks himself. Let me blink and rub my eyes, surely it will be a dream.

For miles around them, out over the valleys and the flatlands, across the glowing scrub, all they can see is monstrous clouds of fire-laced smoke. They’ve got—what?—a couple of hundred people sheltering here. They’re relatively safe.

But there are so many more people out there across the ranges, thousands of them, in isolated farms and leafy towns, from Flowerdale to Pheasant Creek, from Strathewen to St Andrews.

What’s happening to them?

Fire scientist Kevin Tolhurst would report to the Royal Commission into the Black Saturday fires that they unleashed energy equivalent to 1500 times that of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima. They produced radiant heat capable of killing at a distance of four hundred metres. They generated jets and balls of explosive gas able to travel six hundred metres in thirty seconds.

All that energy, that vaporising radiation, those fiery jets and missiles, those gaseous clouds, are unleashed upon the scattered properties and leafy communities of the Kinglake Ranges as the policemen stand helplessly at the CFA in Kinglake West.

It comes first from the sky. Ember attack, it’s called in the literature, but that’s a feeble term for such lethal missiles. The fires race up the slopes, hit the ridgelines and send a barrage out over the hills and valleys ahead. There are spot fires, hundreds of them, breaking out simultaneously: in the bush, the farms, the roadside reserves, the town streets. Because of the spiral motion of the convection column at the fire front, they can come bursting out of the sky from any or every direction at once, spark fires that take off, coalesce. Nowhere on the mountain is safe.

Phil Petschel, a Kinglake CFA veteran and keen student of fire behaviour, explains what happened: ‘Everywhere one of those fireballs landed there was an immediate big fire. There was no build-up, they just

phew!

’—he smacks his hands together—‘they’re there! When a fireball the size of a caravan crashes to the ground with that roaring wind behind it, it’s off!’

Petschel is speaking in the back office of the CFA building, the room that was his home for several weeks after his house on Bald Spur Road burned down.

‘That’s what happened all over,’ he continues. ‘That’s why we got caught out at our end. We were assuming it would come up the slope like a regular fire, but it didn’t. There was a multitude of rapidly growing smaller fires starting everywhere and merging—they didn’t have to travel up—they were just there. It was virtually all up the escarpment in one hit.’

That about sums it up.

While a few hundred refugees shelter behind the hoses of the CFA, hell is breaking loose all round them. Along the foothills and up the escarpment, on into the farmlands to the west, in the leafy streets of Kinglake, firebrands are crashing down, kick-starting fires that merge into a monstrous front. A thousand small battles to save lives and homes are being fought.

An appalling number of them are lost.