Kingmaker: Broken Faith

Read Kingmaker: Broken Faith Online

Authors: Toby Clements

Contents

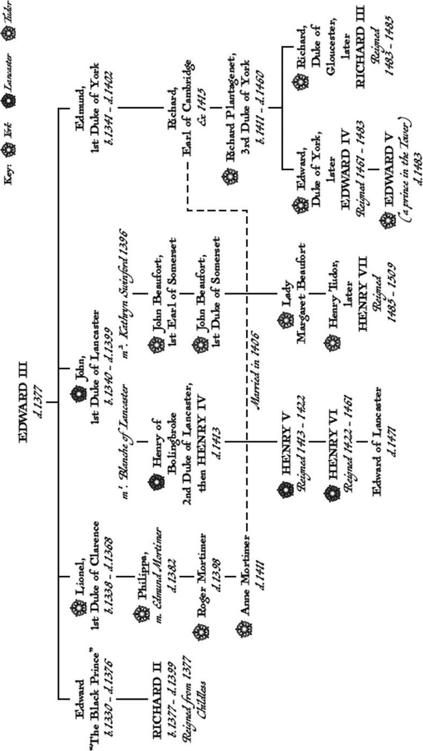

Factions in the Wars of the Roses, November 1463.

Part One: Cornford Castle, Cornford, County of Lincoln, England, After Michaelmas 1462

Part Two: The Priory of St Mary’s Haverhurst, County of Lincoln, Lent, 1463

Part Three: Toward Marton Hall, Marton, County of Lincoln, End of May 1463

Part Four: The North, After Michaelmas 1463

Part Five: South, to Tynedale, Northumberland, Before Easter 1464

England: October, 1463.

The great slaughter of the battle of Towton is two years past, but England is still not at peace. The Northern Parts of the land remain in the hands of the Lancastrian king, while in the south, the princes of the house of York prepare for war.

Uneasy alliances are forged and just as quickly broken: a friend one day might be your enemy the next, and through this land, pursued by the Church and the Law, a young man, Thomas, and a young woman, Katherine, must make their way, bearing proof of a secret both sides would kill to learn.

Bent on revenge for a past outrage, Thomas and Katherine must turn their backs on their friends and journey to the mighty castle of Bamburgh, there to join a weakened king as he marshals his army to take up arms in one of the most savage civil wars in history: the Wars of the Roses.

Toby Clements

was inspired to write the

Kingmaker

series having first become obsessed by the Wars of the Roses after a school trip to Tewkesbury Abbey, on the steps of which the Lancastrian claim to the English throne was extinguished in a welter of blood in 1471.

Since then he has read everything he can get his hands on and spent long weekends at re-enactment fairs. He has learned to use the longbow and how to fight with the poll axe, how to start a fire with a flint and steel and a shred of baked linen. He has even helped tan a piece of leather (a disgusting experience involving lots of urine and dog faeces). Little by little he became less interested in the dealings of the high and mighty, however colourful and amazing they might have been, and more fascinated by the common folk of the 15th Century: how they lived, loved, fought and died. How tough they were, how resourceful, resilient and clever. As much as anything this book is a hymn to them.

He lives in London with his wife and three children. This is his second novel.

Kingmaker: Winter Pilgrims

For Alex, Isabel, Justin and Matt (1967 and 1968–1989), still with us every day, in heart and mind.

OUSE OF

Y

ORK

King Edward IV:

victor of the battle of Towton, crowned king in 1461.

Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick:

architect of the Yorkist victory, later known as the Kingmaker.

John Neville, Lord Montagu:

younger brother of the Earl of Warwick, warden of the East March, commander of Yorkist forces in the north. Tough, resourceful, pitiless.

Henry Beaufort, 3rd Duke of Somerset

Hdefeated leader of the Lancastrian faction at the battle of Towton, attainted but then received into King Edward’s grace in 1463 and made Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber, to everyone’s disgust.

OUSE OF

L

ANCASTER

King Henry VI

Deposed king, in exile in Scotland, returned to England in 1463. His strong labour’d wife Margaret of Anjou is in exile in France.

Ralph Percy

Brother of the Earl of Northumberland, commander of Bamburgh Castle

Lords Roos and Hungerford

Northern lords, with unreliable retinues

Sir Ralph Grey

PrologueCastellan of Alnwick Castle. There is no evidence of him being a drunk.

The Battle of Towton, fought in driving snow on Palm Sunday 1461, saw twenty thousand Englishmen killed, more in one day than ever before or ever since. Although Edward of York carried the day, and was afterwards crowned Edward IV, his victory was only by the narrowest of margins, and it did not mark the end of the Wars.

The old King, Henry VI, of Lancaster, and his indomitable French Queen Margaret, escaped and fled north, to Scotland, where they tried to lure the Scots and the French into attacking newly-crowned King Edward’s much-weakened England. But despite promises of help, neither the Scots nor the French were to be drawn in, and after two years all that was left to the dethroned Henry’s cause were a few castles in Northumberland, mere toeholds in his vanished kingdom.

These castles – Dunstanburgh, Bamburgh, Alnwick – became beacons of hope, attracting the dispossessed, the attainted, and those whose loyalty to the old Lancastrian King could not be bought off with the promise of titles and positions from the new Yorkist one. Among such men were the Dukes of Somerset and Exeter and the Lords Hungerford and Roos, and from these castles they kept the last flames of Lancastrian hope guttering.

But life in these mighty castles on their bleak North Sea shores was far from comfortable. And now the Earl of Warwick, King Edward’s mighty ally, is marching north with ordnance enough to batter down the thickest walls, and with an army at his back bigger than was ever gathered at Towton. So while some pray the castles’ fall will mark the end of a sorrowful chapter in the nation’s story, others pray that some miracle will avert disaster, and that the old King will survive and thrive and return to right the wrongs of the last few years …

After Michaelmas 1462

IT IS THE

hour before noon on the second day after St Luke’s, late in the month of October, and in the grey light slanting through the castle’s kitchen doorway, Katherine inspects the small, skinned body of an animal lying on the scrubbed oak table. The animal is gutted, headless and footless.

‘Rabbit, my lady,’ Eelby’s wife tells her. ‘Husband caught it this morning. Out near the Cold Half-Hundred drain.’

Katherine knows the Cold Half-Hundred drain, and she knows Eelby, who sits with his broad back turned on her, eating his bread so that she can hear him chewing. He says nothing, doesn’t even grunt, but his brawny shoulders are up and she can see he is waiting for something, so she prises open the narrow trap of the animal’s ribs and counts. She makes it thirteen pairs.

‘Not a rabbit,’ she says. ‘A cat.’

Eelby stops his chewing. His wife holds Katherine’s stare for a moment, then drops her gaze to the rushes and rubs her swollen belly. She must be nearly ready now, Katherine thinks, and she must be frightened of what is to come. Her husband swallows his bread.

‘It’s a rabbit,’ he says without turning his head. There are creases of pale skin in the dirty fat of his neck. ‘As wife told you. Killed it meself.’

Katherine knows she still seems odd to them – an interloper in a good dress, small, thin, with her hat pulled down to hide her ear and her already sharp features honed by sorrow and privation – but it has been like this ever since she arrived at Cornford Castle more than a year before, since the first time she led Richard Fakenham on his horse over the two bridges and in through the gatehouse to take possession of her late supposed father’s property.

The curtain walls had seemed taller then, rough grey stone, stained with damp even in the summer months, weeds growing from every crevice and all sorts of filth underfoot. Eelby’s wife stood on an unswept step of the kitchen, washing beetle in hand, while unfed dogs snarled on chains and the air was sour with the smell of their waste.

‘What is it?’ Richard had asked, wrinkling his nose. Eelby’s wife had stared at his bandaged eyes and then looked away, quickly crossing herself and whispering some prayer.

‘A welcome,’ Katherine had told him. ‘Of sorts.’

‘Where is everyone?’ he’d asked.

‘Dead,’ someone had answered. This had been Eelby, the castle’s reeve, emerging from the lower door of the gatehouse from where he’d been watching them cross the fen. She’d disliked him from the moment she saw him – broad and squat, with fleshy ears and small, mean eyes – and neither did he like her.

‘Dead?’ she’d asked.

‘Aye,’ Eelby had said. ‘Every man save meself went north with Sir Giles Riven and we’ve given up on ’em coming home now.’

Eelby had said this as if it were somehow her fault, as if she, Katherine, had been responsible for their deaths, but she had ignored him and had taken a moment to look around at the castle, to note the accretion of filth, the dilapidation of the stone, the rot in the wood. There were jackdaws in the roof, and a bush of some sort springing from between the stones up by the crenellations. Apart from the new stone badge of Riven’s crows that had been put in place of the old Cornford arms, she supposed, the castle looked to have been falling to pieces for some time. It was strange to see how little it had been valued by Riven while Sir John Fakenham and his son Richard had spent so much time, energy and blood to acquire it.