Kino

Authors: Jürgen Fauth

“

Kino

is a fast, complex, exhilarating roadster ride through history and time, a mystery, a documentary, a remarkable remix of reality and imagination. It is the story of a woman who becomes obsessed with her grandfather, a visionary film director in the Germany of the nineteen-twenties through World War II. Tracing the arc of his spectacular decline, she risks a husband and her ordinary life, but uncovers the powerful bindings of family, the sweet, dark loam of loss, and the instant-on high-voltage current of pulp fascism, dirty pictures, propaganda, cultural piracy, art and money.

It's quick but complicated, feverish, trying, speculative, high-minded, and occasionally Goebbels-esque. Everything forced into close and incendiary quarters.Â

KinoÂ

is intoxicating Euro-brew, written with enormous skill and dedication.”

â Frederick Barthelme, author of

Elroy Nights

“Jürgen Fauth's deft mashup of genre and historical period is both a full-throttle literary thriller of ideas and a contemplative examination of film and fascism.

Kino

is a debut of great intellectual force.”

â Teddy Wayne, author of

Kapitoil

“A delirious melange of conspiracy, magic, sex, history, bad behavior, and cinema,

Kino

is a stellar entertainment, and Jürgen Fauth is a writer of rare, sinister imagination.”

â Owen King, author of

Reenactment

“A surprising alternative history.

Kino

brings the golden age of German cinema to light with loving, sometimes gritty, detail and great precision.”

â Neal Pollack, author of

Jewball

“A light-hearted romp that leads straight into darkness and back through the shadows on the wall.”

â Ben Loory, author of

Stories for Nighttime

and

Some for the Day

“This is an elegant book, wrapping the core of a thriller in ideas that play with literary and semiotic conventionsâ¦Jürgen Fauth has a confident touch and is worth watching in the future.”

â David Marshall, Thinking About Books

“Movie nuts, arise! A happy and felicitous debut.”

â Terese Svoboda, author of

Bohemian Girl

“While art may cause mental anguish and distress, ultimately it brings to light the true nature of our existence. That is the brilliance of art, and that is the brilliance of

Kino

.”

â Trip Starkey, The Literary Man

“Part historical fiction, part page-turning thriller,Â

Kino

is a well-told tale written by someone who exudes confidence on every page. Readers are in good hands with Fauth as he masters his realm, creating a world that is wholly his own yet accurate of a past era. His examination of both art's role in society and the portraits of 1920s Germany is worth the read alone.”

â Patrick Trotti,

jmww

An Atticus Trade Paperback Original

Atticus Books LLC

3766 Howard Avenue, Suite 202

Kensington MD 20895

http://atticusbooksonline.com

Copyright © 2012 by Jürgen Fauth. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

ISBN-13: 978-0-9832080-7-5

ISBN-10: 0-9832080-7-7

Typeset in Palantino

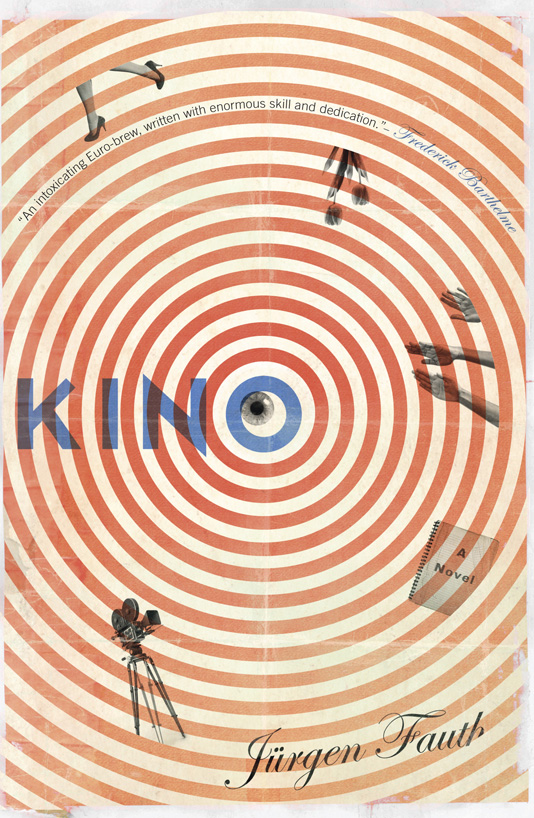

Cover design by Jamie Keenan

“Art is free. However, it must conform to certain norms.”

Joseph GoebbelsÂ

Hotel Kaiserhof, BerlinÂ

March 28, 1933Â

Chapter 1

Mina stumbled and fell headlong into her apartment, smacking her knees and the palms of her hands on the hardwood floor. She bit her lip, cursed, resisted the temptation to cry. Rubbing her bruised joints, she turned to see what had tripped her.

Just inside the door sat a pair of metal cases, knee-high, octagonal, green-grey, a sticker centered on each with Mina's name, unabbreviated, the way nobody ever used it. The label was handwritten in blocky capitals, with a peculiar choice of preposition that made the canisters seem more like presents than parcels: FOR WILHELMINA KOBLITZ.

Mina sighed. She reached for the keys and mail she'd dropped and picked herself up. She had spent the entire day at NYU hospital, where her husband Sam was ill with dengue fever. He'd caught the tropical disease on their honeymoon, which they'd cut short immediately after the resort doctor in Punta Cana diagnosed him. “Bad luck,” the doctor had said. The disease wasn't exactly rare, but there also hadn't been an outbreak in years.

They'd been back for three days now and the marriage was off to a rocky start. The reception had been a disaster, the honeymoon was ruined, and Mina was beginning to resent the long hours at the hospital. This was not how she had envisioned her new life. She spent as much time with Sam as she could, reading in the uncomfortable plastic chair under the glare of the fluorescent lights while her new husband tossed and turned, his eyes glassy, moaning and sweating through his pajamas. In his brief lucid moments Sam complained about the pain in his limbs, the heat, the all-too-real nightmares. Even when he slept, the moaning didn't stop.

Dengue fever could be fatal, but the smug New York doctor had assured Mina that Sam would be fine. He told her to go home. It could be another week before the fever subsided, and she should take care of herself, rest. Mina thought the doctor was too eager to touch her arm. She was attractive, a little short, but busty. Men tended to underestimate her.

The Greenpoint one-bedroom seemed smaller to Mina than ever. They had lived together for almost a year before getting married, and now the apartment was a mess, every open space crowded with wedding giftsâblenders, toasters, sheets, and silverware. The kitchen counter was covered with unopened mail. She hadn't unpacked their suitcases yet.

FOR WILHELMINA KOBLITZ.

Belated wedding presents from a distant relative? The last time she'd heard her full name had been at her college graduation, almost four years ago.

Mina pushed aside a stack of magazines and lifted the canisters onto the kitchen counter. Picking one at random, she popped its twin latches and opened the lid. Inside were four reels of film.

She opened the second container. Three more reels, kept in place by a jammed-in Styrofoam wedge. Sturdy plastic held black celluloid wrapped around the center. Wasn't this stuff flammable? Mina pulled a reel out of the case. She set it on the counter and wheeled it around until she found the end of the film strip, locked down with a pin that held the sprocket holes in place. She carefully unwound it, thinking how odd it was that even though her grandfather had been a filmmaker, she'd never held celluloid before.

Oh,

she thought.

Did this have anything to do with her grandfather?

Mina had never known the old man, a German director who had emigrated to America during the Second World War. He'd made one big flop in Hollywood that still showed sometimes on late-night cable. All his German movies had been lost, and he'd killed himself before Mina was born. Her father refused to talk about him.

The celluloid in her hands was entirely black, and Mina kept unrolling it, unable to stop. She tried to wrap it around the fingers of one hand and turn the reel with the other, but the film kept slipping off. She let it stack up on the counter into a loose loop that curled on its own. After two more revolutions she hit a logo, something like a coat of arms. Then, white words on black: the credits. She held the film up to the neon kitchen light, but the letters were too small to read. She kept unwinding it further, and some of the celluloid slipped off the counter and onto the Swiss espresso machine they'd gotten from Sam's boss. The words grew bigger until there were only two lines, and now she could make out letters, repeated on every advancing frame:

EIN FILM VON

KLAUS KOBLITZ

Into the empty apartment's silence, Mina made a surprised noise not unlike her husband's feverish moans. She was holding in her hands one of her grandfather's lost films.

Chapter 2

From: [email protected]

Date: Saturday, May 10, 2003

Subject: Please Don't Hate Me

Oh baby. I want you to know how horrible it felt leaving you in that hospital bed this morning. Your doctor assured me that the worst was behind you, and I'll be back in three days. I promise. We set up a screening for Sunday, and then I'm flying right back to you. I tried to explain, but you seemed pretty far gone and I don't know if you caught any of it.

I came home last night to what looks like one of the movies my grandfather made in Germany before the war. There were no stamps and when I asked Mr. Palomino who'd brought it, he shrugged. A “messenger boy” who'd made sure he put them inside the apartment. I talked to somebody at the Museum of the Moving Image, and she gave me a number at UCLA and I ended up talking to a guy at the Kinemathek in Berlin, Dr. Hanno something-or-other. He had the worst accent and he was rude, too. I'd forgotten about the time difference and woke him up. But you should have heard him when I mentioned my grandfather's name. Suddenly I was royalty. He asked me all kinds of questions about the film, the condition it's in, the reels, the cansâapparently they're called “cans”âand he asked me to measure the width of the celluloid, and how far from one sprocket hole to the next. He got really worked up. He thinks it's

The Tulip Thief

, my grandfather's first film, made in 1927.

That's a big deal if it's true, Sam. All of his German movies were lost, or at least that's what we thought, and suddenly, there's one sitting in the hallway of our apartment in Greenpoint. I asked how much it'd be worth, but he didn't want to say.

Now here's the thing: it's an old kind of negative, and it's in a weird format, something called

Doppelnockenverfahren

. It's like the Betamax of film. You need special equipment to show it, and the only remaining projector that can handle it is in Berlin at this film museum.

You see? I feel like shit for leaving you and coming over here, but I hope you understand. If this is for real, it's worth a *lot* of money. Maybe enough for a brownstone with a little garden where we can drink our coffee outside. I could pay off my student loans. Lucy and Josh promised they'd come and visit you every day. I haven't told my parentsâmy Dad's probably still mad about the wedding, and grandfather is a touchy subject with him anyway. Well, I guess everything's a touchy subject with him.

I left in such a hurry this morning, Sam, I simply grabbed my suitcase from the trip. I hadn't unpacked yet, so why not just take it, right? Wrong. It's fucking

cold

here and I don't even have a coat or a pair of warm shoes. Instead, I have three bathing suits, my mask and snorkel, and a pair of fucking flippers. I'm such an idiot. I guess it's all been a little much. I don't even speak German. Getting here was awful, too: they made me take off my shoes again at security, and there were five babies on the plane. I counted. Five. I took a Xanax and drank some wine but there was no way I could sleep. My mind kept spinning. Now I'm completely whacked and it's not even noon. Technically, we're still on our honeymoon. We should be making love in the honeymoon suite, drinking piña coladas, and snorkeling in the clear blue water.