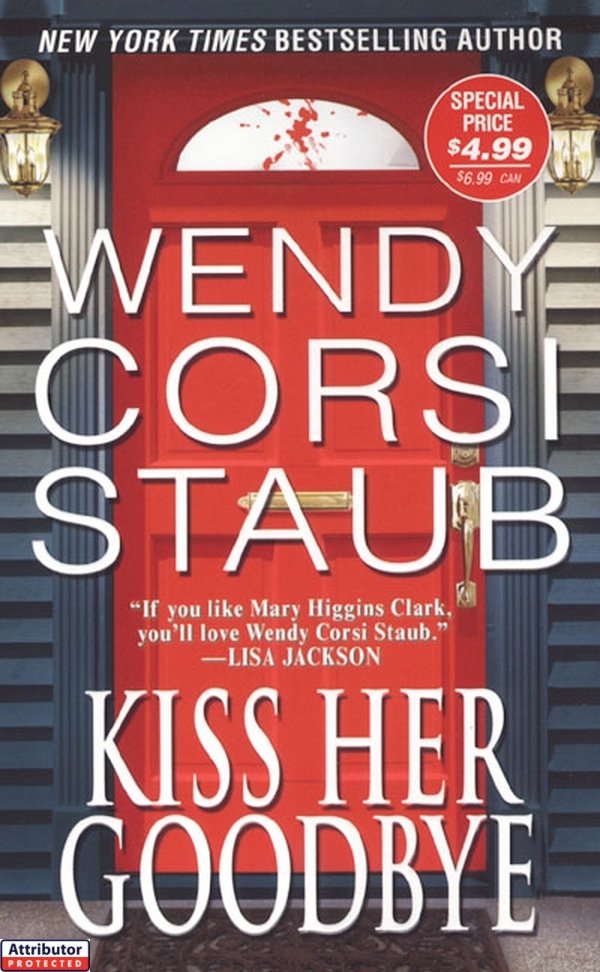

Kiss Her Goodbye

Authors: Wendy Corsi Staub

WAITING TO STRIKE

It's almost time.

Jen has disappeared into the bathroom upstairs with the two children. The plan has already become complicated. At first, it almost seemed prudent to wait, to search for another opportunity to get to Jen when she's alone and vulnerable. But that's starting to become more and more difficult. Especially now that they've gone and changed the locks at 9 Sarah Crescent.

Very clever of Kathleen to do thatâor so she believed. Has it given her a false sense of security? Does she think that simply by changing the locks she can keep at bay any threat to her cozy little world? And did Jen assume, when she checked the front door lock just now, that she's safe because she's on this side of it?

Did it never occur to her that the danger she's instinctively bent on evading might have slipped into the house when nobody was looking?

Giggling children and their unsuspecting babysitter retreat down the hall. The door is left ajar; voices float down the stairs. She's reading a story.

Goodnight, Moon.

Damn Jen for choosing that book to read tonight.

Damn her for dredging up memories better left where they belong: buried beneath decades of bitter resentment . . . and blood lust.

Damn her to hell.

It's time to do just that.

Time to step out of the shadows.

Goodnight, Moon.

Goodbye, Jen . . .

Books by Wendy Corsi Staub

DEARLY BELOVED

Â

FADE TO BLACK

Â

ALL THE WAY HOME

Â

THE LAST TO KNOW

Â

IN THE BLINK OF AN EYE

Â

SHE LOVES ME NOT

Â

KISS HER GOODBYE

Â

LULLABY AND GOODNIGHT

Â

THE FINAL VICTIM

Â

MOST LIKELY TO DIE

Â

DON'T SCREAM

Â

DYING BREATH

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

WENDY CORSI STAUB

KISS HER GOODBYE

Â

Â

Â

ZEBRA BOOKS

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Dedicated in heartfelt memory of my cherished friend,

the gentle Big Man

Jon Charles Gifford

8/7/59â7/8/03

“Here's to you and those like you.

Damned few left.”

the gentle Big Man

Jon Charles Gifford

8/7/59â7/8/03

“Here's to you and those like you.

Damned few left.”

Â

Â

And with love to William Pijuan, aka Uncle Bill,

who bravely carries on.

who bravely carries on.

Â

And, as always, to Mark, Morgan, and Brody.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The author gratefully acknowledges, in reverse alphabetical order for a change, Wendy Zemanski, Walter Zacharius, Steve Zacharius, Mark Staub, John Scognamiglio, Joan Schul-hafer, Janice Rossi Schaus, Laura Blake Peterson, Laurie Parkin, Doug Mendini, Gena Massarone, Kelly Going, Kyle Cadley, and Danielle Boniello.

PROLOGUE

August

Â

Her thoughts, that Tuesday night as she walks along the edge of the road, are mainly occupied by the first day of school tomorrow.

What she'll wear, who she'll have for homeroom, and whether she'll get third or fourth period lunch. Seniors always get one or the other of the later lunch periods. That'll be a nice switch. Last year, she had first period; who wants sloppy joes or egg salad at 10:20 in the morning?

The pothole pocked pavement of Cuttington Road shines in the murky glow of streetlights; the strip of ground that borders it is still muddy from this morning's hard rain.

Ma always reminds her to walk in the gutter, not the road, on her way home from her job at the fast-food place out on the highway. But she can't walk in the mud; she's wearing sandals.

And anyway, it's less than half a mile, and there isn't a lot of traffic on this old, winding back road leading to their apartment complex at this time of night. A year or two ago, there wasn't any through traffic at all; the only thing out here in the woods was Orchard Arms, a cluster of boxy, stucco, two-story buildings with rectangular wrought-iron balconies cluttered with potted impatiens, tricycles, and hibachis.

Then bulldozers rolled in and created a development where the woods used to be. They call it Orchard Hollow, probably because of all the apple trees they tore down to make way for the houses. Now, farther down the road, just past Orchard Arms, cul de sacs branch off from Cuttington Road like jeweled fingers on a work-roughened hand.

Two- and three-story houses with two- and three-car garages sprang up where there used to be only trees and brambles. In the garages are shiny cars and SUVs; in the homes are people who complain about the ruts and poor lighting along the old road that leads to Orchard Hollow. It's always been bad but nobody other than the apartment complex's residents ever cared until now. The construction equipment has torn up the pavement worse than ever, but they're still building back there.

The new houses have broad decks and brick terraces instead of wrought-iron balconies. They have real yards with raised beds of roses, wide gas grills, and elaborate wooden swing sets. Some of them even have in-ground pools.

On the hottest days of this summer, as she sat out on the balcony, she could sometimes hear the sound of splashing and gleeful shouts in the distance.

She often wondered what it would be like to make friends with one of the girls who ride her bus. Then she might be invited over to one of their pools to swim.

But so far, that hasn't happened. The girls from the development stick together, and she, as the only kid her age living in Orchard Arms, keeps to herself on the bus. Sometimes she eavesdrops on the other girls' conversations when they talk about things that interest her. Things like boys at Woodsbridge High and sales at Abercrombie & Fitch over at the Galleria. But when they discuss things to which she can't relateâlike curfews and overly strict fathers and nosy mothers who are always home, always asking questionsâwell, then she tunes them out.

She sticks to the very edge of the pavement as she walks, doing her best to pick her way around the puddles that fill the potholes. Her toes are getting wet and dirty anyway.

Tomorrow, she'll have to put on regular shoes again for the first time in two months, she thinks with a tinge of regret. Regular shoes and regular clothes. In western New York, the days of sandals and shorts and tank tops are too fleeting as it isâyou'd think Woodsbridge High would allow students to wear them through the warm days of early September, but nope.

What a waste of a pedicure, she thinks, remembering how painstakingly she polished her toenails pearly pink just this morning while she was sitting on the balcony watching the rain.

She hears a car splashing toward her from behind and steps farther off the road to let it pass.

It doesn't pass.

Gravel crunches beneath the tires as it slows; the headlights illuminate the road before her, casting an eerily long, distorted shadow of herself.

She wonders, as she turns toward the blinding lights, whether it's somebody she knows from Orchard Arms, stopping to give her a ride.

Her next thought, a belated thought, is that Ma always tells her to walk facing traffic, not with it, so that she can see what's coming toward her.

And her last coherent thought as the car door opens and she is dragged roughly inside is that she never, ever would have seen this coming.

PART I

OCTOBER

ONE

“Mrs. Carmody?”

Startled, Kathleen glances up at the orthodontist's bleached-blond receptionist.

“Yes?”

“We need your insurance card again.”

With a sigh, Kathleen puts aside an issue of

Rosie

magazineâa relic of a bygone era when there actually was a

Rosie

magazineâtakes her purse from the back of her uncomfortable chair and crosses the crowded waiting room. Her ten-year-old son Curran, absorbed in his Gameboy, is the only one who doesn't look up.

Rosie

magazineâa relic of a bygone era when there actually was a

Rosie

magazineâtakes her purse from the back of her uncomfortable chair and crosses the crowded waiting room. Her ten-year-old son Curran, absorbed in his Gameboy, is the only one who doesn't look up.

Kathleen fishes for the card in her wallet, hands it to the woman, and waits while she examines it, frowns, photocopies it, and frowns again.

“Is this new insurance?” the receptionist asks.

“Not since we started coming here in May.” She wonders if the receptionist is new. She's never seen her here before.

“Not a new group number?”

“Nope.” Kathleen sighs inwardly. What is it with insurance? It's been six months since Matt switched jobs and they moved to western New York, but every doctor, dentist, and orthodontist appointment brings another round of complications.

The woman spins her chair toward a computer, taps a few keys with her right hand while holding the insurance card in her left. The computer whirs, and she glances up. “It'll be a few seconds; I just have to check something, Mrs. . . .

Katie?

”

Katie?

”

Katie.

A name from the past. Which means that the unfamiliar receptionist is also a name, a voice, a face from the past.

It's Kathleen's turn to frown, in that vague, polite,

have we met?

manner she's perfected since the move.

have we met?

manner she's perfected since the move.

“You're Katie Gallagher, right?”

Not anymore, thank God.

“I used to be.” Kathleen forces a pleasant smile. “It's Kathleen Carmody now.”

“I'm Deb. Deb Duffy, I used to be, but now I'm Deb Mahalski.”

The name doesn't ring a bell. Not that it would. Kathleen did her best to block out just about everyone she used to know. It's easier that way.

“I thought you moved away years ago,” the woman chatters on.

Kathleen wants nothing more than to grab Curran and his Gameboy and bolt, but that's out of the question. This isn't the first time she's run into somebody who used to know her. And anyway, the receptionist is still holding her insurance card.

“I'm . . . I did, but I'm back,” Kathleen murmurs, absently noting Deb Mahalski's impossibly long, curved, crimson fingernails and wondering how she manages the keyboard.

“Where are you living now?”

“Woodsbridge.”

Kathleen watches the woman glance down at her file on the desk; sees her overly plucked and penciled-in eyebrows rise. “Orchard Hollow? You've come a long way since Saint Brigid's.”

So that's it. We were Catholic schoolgirls together in another lifetime.

“Did you hear they tore down the church and school a few years ago to build a new Wegman's?”

“I heard.”

“That's your son?” Deb asks, with a nod at Curran.

“Yes.”

“I have two girls, three and five.” She gestures her poufy pile of hair, caught back in a plastic butterfly clip, toward a framed photo on the desk. “Do you have other kids?”

“A younger son. And a daughter. She's . . . older.”

“And you're married?”

“Mmm hmm.”

It's not as though she can dodge the questions. After all, few taps of the computer keys would reveal everything anyone would want to know about her life.

Not everything.

Nobody knows everything. Not even Matt. Nor the children.

And they never will

, Kathleen assures herself, clasping her trembling hands into fists within the deep pockets of her corduroy barn coat.

, Kathleen assures herself, clasping her trembling hands into fists within the deep pockets of her corduroy barn coat.

Â

Â

“I'm home! Sorry I'm late, Jen!” Stella Gattinski calls as she simultaneously steps from the attached garage into her kitchen and out of the brown leather pumps that have tortured her feet all afternoon.

“It's okay, Mrs. Gattinski.”

Jen Carmody, the “bestest and most beautifulest babysitter in the whole wide world,” according to Stella's two-year-old twin daughters, smiles up from the raised brick hearth in the adjoining family room, where a stuffed animal tea party is in progress.

The April day the Carmody family moved to Woodsbridge from the Midwest was one lucky day for Stella. Wholesome Jen is terrific with Mackenzie and Michaela, and she's at the perfect age: about thirteen. Old enough to be responsible for two small children, and too young for dating, driving, and most extracurricular school activities.

She comes every Wednesday to meet the twins when the day care bus drops them off. Wednesdays are Stella's late day at school; she's the French club advisor and that's the afternoon they meet.

Before Stella hired Jen, she was forced to rely on Elise Gattinski, aka the mother-in-law from hell, for Wednesday child care. Her own mother used to do it, but ever since Daddy's death last year, Stella hates to ask her. Mom's grown increasingly frail; she isn't up to caring for a pair of twin preschoolers.

Kurt's mother is hardly frail and she frequently offers to help out, but Stella always loathed using her as a regular babysitter. Not a week went by when Elise didn't make some dig about working mothers neglecting their children's needsâand, even worse, their husbands' needs. Thank God Stella no longer needs her help, unless she's in a pinch.

“Mommy, Jen doesn't have to leave now, does she?”

“Yeah, Mommy, she said we can play Candyland again after this,” Michaela promptly joins Mackenzie's whining. “Can you go back to work?”

Stella grins. “Sorry, kiddo. You're stuck with me.”

There's a brief commotion, then Michaela breaks off midwail to announce, “Mommy, guess what? Jen rescued a ladybug!”

“Yeah, the ladybug landed on her arm and I hate bugs so I wanted to kill it but Jen wouldn't let us,” MacKenzie puts in.

“She says never kill anything,” Michaela adds, “not even yucky bugs! Because they want to go home to their mommies.”

“Jen's right,” Stella says approvingly. “Did anyone call, Jen?”

“Just Mr. Gattinski.” Jen doesn't seem to mind Mackenzie's hands attempting to braid her long blond hair. “He said to tell you he's got a late meeting and to eat without him.”

Stella's grin fades. Another late meeting. That's the second time this week, and it's only half-over.

“Kenz, get your hands out of Jen's hair,” she says absently, wondering who Kurt's meeting with tonight.

His promotion to vice president at Lakeside Savings and Loan seemed like a blessing, coming at the tail end of Stella's extended maternity leave. But that was almost two years ago, when money was scarce and family togetherness was not. Their household had just doubled in size, sweeping a dazed Stella from busy middle school teacher to invalid on bedrest to stay-at-home mom. Quite honestly, Kurtâwith his banker's hoursâwas underfoot and on her nerves at that point, anyway.

Now she's back to work; he's a vice president; they've got a savings account, a Volvo station wagon, a weekly housekeeper, and this newly built center hall Colonial in Orchard Hollow.

Not to mention the most adorable little girls on the planet.

Life couldn't be better.

Really.

After checking the clock on the microwaveâ5:26 already? âStella fumbles in her wallet for a twenty and a ten. Jen's been here since three, and her hourly rate is only eight dollars, but Stella gives her ten an hour and always rounds up. The twins are a handful. Plus, it's only one afternoon a week.

“Girls, get off Jen's lap so she can stand up,” Stella says.

Her daughters ignore her.

Jen giggles as Michaela throws her arms around her and gives her a bear hug.

Depositing her purse on the breakfast bar, Stella strides across the toy-strewn carpet, money in hand. She deftly plucks a wriggling Mackenzie off of Jen and pries Michaela's arms from around Jen's neck.

“I know you guys love Jen, but she has to go home. Her mommy is probably wondering where she is.”

And your mommy is wondering where your daddy is.

“Please tell your mom I'm sorry it's so late, Jen.”

And your mommy is wondering where your daddy is.

“Please tell your mom I'm sorry it's so late, Jen.”

“Actually, my mom's not home. She had to take Curran to the orthodontist in Amherst at four and they never get out of there for hours.”

That's true. Kathleen Carmody was complaining about it just the other day when Stella ran into her at the supermarket. She mentioned that her older son has had three appointments with Doctor Deare so far and he's always running behindâand that his waiting room magazines are at least a year old.

“Maybe I should take up cross-stitch or knitting,” Kathleen said, rolling her green eyes. “I've got years of this ahead of me. Our dentist is already positive that Riley”âthe youngest Carmodyâ“is going to need braces, too.”

But not Jen. Stella finds herself admiring the teenager's perfectly even white smile. Add that to her wide-set brown eyes, fine bone structure, and willowy build, and she looks like a fresh-faced fashion model. She even has a quirky characteristic on par with Cindy Crawford's mole and Lauren Hutton's widely spaced front teeth: a thin streak of white hair running through the golden brown hair of her left eyebrow.

Next to her teenaged sitter, Stella feels frumpier than ever. Her own unruly dark blond hair is pulled back into a black velvet headbandâthe kind that went out of style more than a decade ago for all but New England finishing school students. The last twenty pounds of maternity weight still cling stubbornly to her hips and stomach, yet Stella refuses to acknowledge that they might be here to stay. That's why she's still wearing skirts and tops she bought a few months into the pregnancy, instead of something more streamlined and fashionable. She refuses to buy new clothes in size fourteen.

She notes with envy Jen's slender figure in jeans and a simple tucked-in T-shirt. Oh, to be young and skinny again. . . .

“Do you still need me on Saturday night, Mrs. Gattinski?” Jen brushes off her jeans and casually tosses her silky hair back over her shoulders as she stands.

“Saturday night . . . yes! We've got that Chamber of Commerce dinner. I almost forgot. Mr. Gattinski will pick you up at seven.”

“I can walk over,” Jen protests, and murmurs her thanks as Stella hands her the thirty dollars.

“You're welcome. And no, you can't walk over; it'll be dark by seven. In fact . . .” Stella glances over Michaela's red hair at the sliding glass doors that lead out to the deck and fenced yard. “It's almost dark now. Come on, I'll drive you home. Girls, where are your coats?”

“That's okay, don't do that, Mrs. Gattinski. By the time you get them bundled up and into the car seats, I'll be home.”

“I don't know . . .” Stella looks again at the darkness falling. The thought of packing the kids into the car

is

exhausting, butâ

is

exhausting, butâ

“I'll be fine. I'll see you two on Saturday, okay?” Jen plants a kiss on each twin's cheek and heads for the front door.

As it closes behind her, Stella cuddles her daughters close on her lap and smooths their hair, the same shade and texture as her own. She sighs in contentment. Another long day has drawn to a close. All she wants to do is throw on sweatsâeven better, pajamasâand collapse on the couch.

“I miss Jen,” Mackenzie laments.

“Me, too,” chimes the inevitable echo.

You should have insisted on driving Jen home,

Stella chides herself, glancing again at the shadows beyond the sliding glass door.

It isn't a good idea for a teenaged girl to be out alone after dark.

Stella chides herself, glancing again at the shadows beyond the sliding glass door.

It isn't a good idea for a teenaged girl to be out alone after dark.

Not that this neighborhood isn't the safest around. It isn't like their old street in Cheektowaga, where there were three car break-ins in the month before they moved. But still . . .

April Lukoviak.

The name flits into Stella's thoughts, sending a ripple of uneasiness through her.

April Lukoviak, who lived with her mother up the road at Orchard Arms, has been missing for weeks nowâsince right around Labor Day. There were fliers up all over the development back when school started. They were cheap, photocopied fliers made by the people who lived in the apartment complex, featuring a poorly reproduced black-and-white image of a pretty teenaged girl with long, straight blond hair like Jen's.

At first, the other mothers at the bus stop were disconcerted by the fliers. They kept a wary eye even on their teenaged children, especially the girls. Then people started talking about how April didn't get along with her mother, who supported the two of them with food stamps, welfare checks, and by tending bar. People said that April was always threatening to run off to California, where her father reportedly last lived. The police seemed to think that theory made sense.

After awhile, September rains blurred the typed descriptions of April. Fierce autumn winds blew in off Lake Erie to tear the fliers from the development's lampposts and slender young trees, blowing them away altogether.

But every once in a while, when Stella passes Orchard Arms or goes through the drive-through at the fast-food restaurant where April worked, she finds herself thinking of her. She wonders what ever happened to her; wonders if she really did run away.

If anything ever happened to Jen, you'd be responsible. Next time, you'll insist on driving her home. After all, bad things can happen in safe neighborhoods, too.

Other books

Crystal Gryphon by Andre Norton

Firetrap by Earl Emerson

Convincing Alex by Nora Roberts

The Good Rat by Jimmy Breslin

Double Tap by Lani Lynn Vale

Hands of the Ripper by Adams, Guy

Rewarded by Jo Davis

Sheikh’s Fiancée by Lynn, Sophia, Brooke, Jessica

Whisper by Chrissie Keighery

Parallel Myths by J.F. Bierlein