Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death (36 page)

Read Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death Online

Authors: Katy Butler

Tags: #Non-Fiction

was still Valerie. We had transcended nothing. I would need her

forgiveness, as she would need mine, until the end of our days.

I had expected that my father’s death would catapult my mother

and me into a redemptive and loving realm. But the man who used

to croon “don’t escalate” was a memory in my neurons, a few fold-

ers of letters, a closet full of old clothes, a never-finished book, and some ashes buried on a hill, lying in a streambed, and remaining in

a brown plastic box. He would fear no more the heat of the sun, and

fear no more the critics he had imagined would tear his book apart.

He would yearn no more for reconciliation with Michael, and never

again would he make my mother beautiful by telling her so.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 231

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 232

1/31/13 12:27 PM

VI

Grace

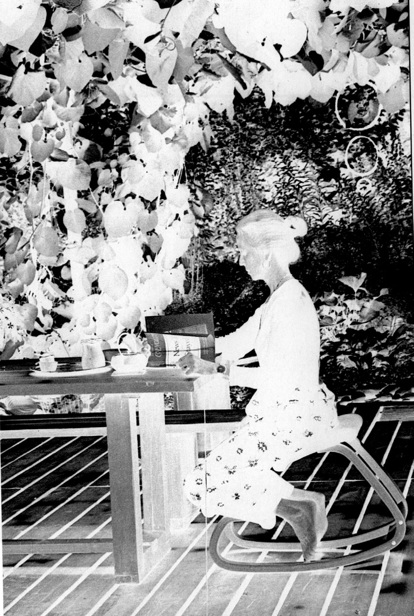

Self-portrait by Valerie Butler, Pine Street, Middletown, Connecticut.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 233

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 234

1/31/13 12:27 PM

Valerie Makes

Up Her Mind

My mother and I spent eleven months after my father’s

death apart, grieving separately. Her life, she said, felt

empty and without meaning. Toni, she said, felt much the

same. She repeatedly told me how proud my father had been of

me and how much he had loved me. “You and I did a great job

taking care of Daddy,” she would say. “With your brains and my

practical skill, we were a great team!”

I let my hair go gray and cried my way through six free grief

counseling sessions offered by my local mental health center.

My father’s death had marked me, and though I did not wear

black, I wanted it to show. I read books about the history of

pacemakers, trying to understand what had happened to us,

and more books about the health care system. I proposed a

story about my father’s death to the

New York Times Magazine

. I

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 235

1/31/13 12:27 PM

236

katy butler

was haunted by traumatic images of my mother shouting at my

father, of his dying, and of our fight at the graveyard on Indian

Hill. I did not visit her for Christmas. I was in awe of all she had

done for my father, and knew I could not have cared for him

nearly as well, and I understood the suffering that had led to

her to be cruel to a man she deeply loved. Yet I was still angry.

In January, to celebrate my sixtieth birthday, I cashed in my

frequent-flyer miles, pretended that my father had given me a

small legacy (all his assets flowed automatically to my mother)

and flew to Bali, where I went repeatedly to a healing water

temple called Tirta Empul. Tirta Empul consisted of a series

of outdoor courtyards surrounded by palm trees. Near the

entrance was a long, rectangular stone bath, into which water

poured constantly from the mouths of fountains shaped like the

heads of gods. I spent a full day there, in a soaked sarong and

a traditional white Balinese tunic called a

kebaya,

leaving offerings of flowers and incense by the stone heads and plunging my

head under their pouring mouths over and over until my body

was chilled, saying to myself,

purify me.

It was as if for seven years I’d slept in a room full of secondhand smoke and at Tirta

Empul I finally washed the dirtiness and disgust of my father’s

death out of my bones.

I came out dazed and changed into dry clothes. The inner

courtyards of the temple were crowded with processions of

Balinese men and women carrying towers of fruit and flowers

on their heads, while others carried the carved god-images they

called

barongs

which reminded me of Chinese New Year’s drag-

ons. I sat among the crowds, listening to gentle gonging of the

gamelan. It was a holy day, full of life.

At a bar in Ubud, I watched Barack Obama, half a world

away, take his first oath of office as president, to cheers all

round from Australians and Balinese amazed by the sight of

a brown-skinned American president. At an Internet café full

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 236

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

237

of cathode-ray machines, I got an e-mail from an editor at the

New York Times

saying she was interested in my story about

my father, his pacemaker, and the perverse financial incentives

within medicine that had encouraged his overtreatment.

My mother stayed put in Middletown. She answered two

hundred condolence letters, lifted weights at the Wesleyan

gym, and studied tai chi with a new neighbor. She made a few

new friends—mainly widowed, divorced, and single women—

and decided to go to South Africa to visit a favorite goddaughter,

and to get a Siamese cat. She built herself a cat-scratcher out

of wooden posts and coiled rope, and asked me if I’d take her

cat after she died. I lied and promised I would, even though I’m

allergic to cats. Then she fainted alone in the house, and did not

tell me about it. She simply said she’d decided against going to

Africa, and against the cat.

She signed up for a medallion from a company called Life-

line, with a button to summon emergency services. She also

went to Dr. Fales’s office, signed the forms, and held out her

ankle for her own orange, plastic DNR bracelet.

“When Jeff’s health and mind deteriorated,” she wrote in her

journal:

I knew I had to do the hard thing and let him die and not

prolong his life with antibiotics, etc. Now as my heart gives

me problems I am thinking of the best way to deal with my

decline. The thought of going to live in a retirement “home”

is simply a horrible idea to me. To be housed, even at The

Redwoods, with a lot of old people waiting to die is not my

idea of the way to go.

She reread a book she owned called

Last Wish,

in which Betty

Rollin described helping her terminally ill mother take a fatal drug

overdose. She told me that she was fantasizing about getting a

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 237

1/31/13 12:27 PM

238

katy butler

plastic hose for the exhaust pipe of her car. “There is a prospect of

a timely escape,” she wrote in her journal, “and I will take it. I need

to make things clear to Michael and Jonathan so that Katy does

not have the burden of helping me out on her own.” I flew East.

On a spring day nearly a year after my father’s death, my mother

and I drove through a rainstorm to the Longwood Area of Bos-

ton, a jumbled maze of traffic-choked streets, streetcar lines,

and high-rise hospitals surrounding Harvard Medical School.

While walking together in Wesleyan’s indoor athletic cage, I’d

been shocked to discover that she could not complete a single

circuit without stopping to rest. For decades she’d had a heart

murmur—a sign that her heart’s mitral valve did not close prop-

erly—but it had given her no trouble. But the wear and tear of

the years had thickened and weakened the valve to the breaking

point. In the course of her life, it had opened and closed nearly

three billion times. It was flabby and loose, and encrusted with

calcium thrown off by her aging bones.

Before going to Boston, she and I had visited a Middletown-

area cardiologist (not Dr. Rogan) who’d told her that her aortic

valve, too, was stiffened and narrowed. Tapping away on his

laptop, he told her to get both heart valves replaced at Yale-

New Haven. He wrote down the phone number of a surgeon he

trusted and handed it to her, as if that was that.

But rather than calling the number, I’d done an Internet

search and discovered that Brigham and Women’s Hospital in

Boston, a successor of the old Peter Bent Brigham, was a pio-

neer in minimally invasive valve replacement surgery. Perhaps, I

thought, my mother could have her heart valves replaced with-

out having her breastbone sawed open from the top of her jugu-

lar notch at her collarbone to the bottom of her xiphoid process

at the base of her ribs.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 238

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

239

My mother had good feelings about the Brigham. It was

there, in 1971, that she’d gotten her second, possibly life-saving

mastectomy under the care of the pioneering surgeon Francis

Daniels Moore. By the time my mother and I returned to the

Brigham, however, Moore was only a revered and troubling

memory.

He had retired from surgical practice in 1981 at the age of

sixty-eight. In his eighties, thanks largely to antibiotics and the

safe surgical techniques he’d researched extensively, he survived

Legionnaire’s disease, two hernia surgeries, and the removal of a

benign mass from his pancreas. Then he developed a leaky heart

valve and congestive heart failure. The Brigham was a leader in

heart surgery in the very elderly, but his doctors did not think he

was a good candidate for it, and put him on medication. Short

of breath, he lived a constricted and declining life.

In the late fall of 2001—a month, as it happened, after my

father’s first stroke—Moore shot himself to death in the study

of his home in the Boston suburb of Westwood. He was eighty-

eight. His death was traumatic, bloody, and old-fashioned. And

in wresting control of its timing and manner from the advanced

medicine that he’d helped create, Moore remained the hero of

his own journey. My mother, I suspected, would want the same.

I was nervous and preoccupied as we arrived at the hospital,

and not just by the rain pouring in sheets off the windshield. On

our drive from Middletown, just after pulling out of a tollbooth

onto the Massachusetts Turnpike, my mother had abruptly

stopped the car in the active right lane of traffic, seemingly

oblivious to the danger, to turn over the wheel to me. As I hur-

ried into the driver’s seat, looking over my shoulder at a truck

slowly accelerating out of the tollbooth behind us, I wondered

for the first time whether her mind was starting to slip.

I’d earlier sent her an article I’d found in the

New York Times,

headlined, “Saving the Heart Can Sometimes Mean Losing the

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 239

1/31/13 12:27 PM

240

katy butler

Memory.” It suggested that somewhere between a tenth and a

half of heart bypass patients tested poorly on memory and other

thinking skills six months after surgery. Other studies suggested

that the deficits persisted for years. Doctors sometimes called

the phenomenon “pump head” because it was popularly thought

to affect people who’d been hooked up to a heart-lung bypass

pump, even though patients who’d had joint replacements and

other major surgeries also suffered similar mental declines.

Some doctors speculated that the brain damage occurred when

surgeons clamped and unclamped the aorta, the body’s largest

blood vessel, breaking up the coating of fat and calcium inside

it and dislodging a snowstorm of tiny clots that traveled through

the bloodstream to the brain. The clamping could also dislodge

larger clots: many studies show that 2 percent to 5 percent of

those undergoing heart surgery suffer strokes as well.

I had other fears that I did not share. Earlier that year, the

eighty-seven-year-old mother of a close California friend named

Christie had taken three gruesome months to die in Florida

after being shuttled back and forth repeatedly between a hospi-

tal and a nursing home. She’d been rushed into valve replace-

ment surgery by her doctor, and Christie, to her later regret, had

pressed her mother to overcome her reluctance and go ahead.

The surgical shock had been too much.

We entered Brigham and Women’s through a dark and bus-

tling front entrance. The place had the disjointed, eternally-

under-construction feel of a modern airport. We rode up an

escalator and crossed an airy pedestrian bridge into the soar-