Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death (9 page)

Read Knocking on Heaven's Door: The Path to a Better Way of Death Online

Authors: Katy Butler

Tags: #Non-Fiction

46

katy butler

letters that my mother wrote to relatives in South Africa, just

how happy they were made by how happy Brian made me.

After Brian left, my father and I walked down one morning

to the Wesleyan pool. The lifeguards had come to expect him,

and they set out the disability hoist to lift him, like a lineman in

a bucket, in and out of the water. On the way home to the house

on Pine Street, he told me he was “on permanent holiday.” Long

before his stroke, he’d become expert in enduring what he could

not change—from his lost arm to his sons’ emotional distance to

my mother’s chronic discontent—and he used that capacity now.

Meanwhile, my mother had grown. A retired Wesleyan math

professor had taught her how to balance her checkbook, and

once a month she took it down to her tax accountant’s office,

where a bookkeeper helped her chase down the errors that set

her totals off by a dollar or two. A neighbor, a former social

worker, had suggested she make a list of the caregiving tasks she

abhorred, and hire someone. Through the Wesleyan grapevine,

she’d found a gentle older African-American woman named

Annie, and for ten dollars a visit, Annie came in and gave my

father a shower three mornings a week.

But just as things stabilized, my parents’ lawyer, an old family

friend, advised my mother to sell the house and buy into a “life

care community” before my father got too addled or helpless to

qualify. My father was not going to get better, she said. He was

going to get worse. Panicked and sleepless, my mother towed my

father around assisted living places, rejecting one for its Jell-O and

Lutheran religiosity, others for their distance from any town, and

still others for their predominance of Republicans in golf pants.

She was still on the banks of vigorous, early old age, on the

far side of the river from my father’s helpless desolation. She

didn’t want to trade her autonomous though burdened life—

her friends, her garden, her currently unused sewing room, her

weekly trips to Freddy’s Middlesex Fruitery on Main Street for

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 46

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

47

the crispest green apples and freshest red oak lettuce—for an

expensive, overheated shoe box of an apartment, with over-

cooked food, in what she called a “hen house.” But she was

terrified of running out of money and of disasters she couldn’t

foresee and exhausted by maintaining the house and its acre of

trees and grounds while taking care of my declining father. To

my dismay, she’d already had a real estate agent in to price the

house. Our family had lost so much; I did not want to lose that

house as well—that island of beauty and order, that reminder of

the life my brothers and I had once lived.

Armed with a referral from the catastrophe doctor, I drove my

parents to West Hartford to meet a new lawyer, this one a pio-

neer in a specialty called “elder law.” He was a ferrety little man

in his forties with a straw moustache. His own father had been

struck by Alzheimer’s disease in his late fifties. By the time the

old man died in a nursing home, there was nothing left for his

widow or children.

The lawyer sat us down at a blond conference table and told

my parents to transfer all the mutual funds they held outside

their IRAs into my name. If my father had to enter a nursing

home, we would first “spend down” their IRAs. Then Medicaid,

the program intended for the poor, would pick up his bills, just

as it covers 45 percent of the more than $137 billion that the

nation spends annually on long-term care. If my parents didn’t

sequester some money, the lawyer said, my mother would risk

what he called “spousal impoverishment.” Medicaid would not

cover my father’s nursing care until they spent down most of

their assets.

If, on the other hand, some money was moved promptly into

my name, that money could be used to pay for my mother’s care

when she got frail, and perhaps even for an inheritance for my

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 47

1/31/13 12:27 PM

48

katy butler

brothers and me. The scheme, I hoped, would give my mother a

backup plan and stop her stampede toward assisted living. She

could stay in the house that felt like an anchor to us, hire more

help, and manage on her own.

“Do it now,” the lawyer said, fingering his moustache.

Changes in the law were afoot to make what we were contem-

plating more difficult. Technically, the scheme was not illegal:

parents transfer assets to adult children legitimately all the time,

and as long as my father needed no Medicaid help for at least

three years (since extended to five) nobody would scrutinize the

financial transfer.

It was the sort of thing my father, when he could speak,

would have called “sharp practice.” He sat in a chair, a compli-

ant, voiceless witness.

The lawyer laid out a sheaf of documents for us to sign: far

more extensive (and expensive) than the living wills and “durable

power of attorney for health care” documents they’d signed years

earlier. First came updated wills and new “advanced directives”

declaring that they wanted no life-sustaining treatment if they

were in comas or likely to die within six months. (The documents

said nothing, I’d later realize, about dementia or tiny internalized

life-support devices like pacemakers.) Then came new “durable

power of attorney for health care” forms, giving my mother and

me the authority to make my father’s medical decisions when, in

the sole opinion of the family doctor, he could no longer make

his own. Finally, there were documents entrusting me with my

mother’s medical guardianship, power-of-attorney forms giving

my mother and me free rein over my father’s financial affairs, and

similar ones giving me comparable authority regarding my mother.

My mother showed my father where to sign, and in his new,

oddly miniaturized and rickety hand, he did. He’d been the

family money manager and the ballast to my mother’s volatile,

wind-filled sails—her rock and our paterfamilias. Now, with my

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 48

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

49

brothers still keeping their distance in California, shards of his

shattered role were falling to her and to me, his disorganized,

bright, well-meaning daughter.

As the notary turned the long legal pages and busied herself

with her stamps, I looked at the language that foreshadowed

our new world. We had no idea how flimsy these paper amulets

would turn out to be.

After my mother and I called Fidelity and set the money transfer

in motion, I took my father for a walk in the forest surround-

ing Colonel Clarence Wadsworth’s turn-of-the-twentieth-century

wedding-cake mansion recently refurbished by the city of Mid-

dletown. My parents and I had walked its woods and streams

for decades, flouting the nuns in the days when it was a private

religious retreat center run by Our Lady of the Cenacle. I held his

hand. He dragged his right foot. Autumn leaves lay everywhere.

I asked him if his life was still worth living.

“Are you talking about

Do Not Resuscitate

?” he asked pro-

nouncing it

Re-Sus-Ki-Tate

. I wasn’t thinking that specifically, but I nodded anyway.

He said my mother would have been better off if he’d died of

his stroke. “She’d have weeped the weep of a widow,” he said in

his garbled, poststroke speech. “And then she would have been

all right.”

As we shuffled through the fallen leaves, I thought of my

English grandmother Alice, whom I’d hardly known. She’d died

in 1963, at the age of eighty-three, on the custodial wing of

a South African hospital, the first of our family to die among

strangers. Five years of devastating strokes had left her so

incontinent, incoherent, and angry that she refused to eat, and

her devoted husband Ernest and his unmarried sister Mary had

been forced to stop caring for her at home.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 49

1/31/13 12:27 PM

50

katy butler

Alice’s years of lingering misery—then a far rarer pathway to

death than it is today—provoked a spiritual crisis in several of

my father’s four siblings, and they openly wondered why God

was punishing her this way. “The noises she made were impos-

sible to interpret . . . and did little for my always wavering faith

in a merciful God,” my late uncle Guy, a well-known South

African poet, wrote in his memoir about her last, worst years.

Within hours of her death, he stood with my stunned grandfa-

ther at the foot of her bed, contemplating her fixed sightless

eyes and emptied form. “She was no longer the painful parody

of what she once had been,” Guy wrote. “She was dead, bless-

edly dead, and free at last, beyond the agony of fumbling for

words and meanings in an eighty-three-year-old body.”

Her husband, my grandfather Ernest, died in 1965 at the age

of seventy-nine, at the tail end of times when medicine did not

yet routinely stave off death among the very old. He went to his

backyard woodshop one day, completed a set of chairs he’d left

unfinished for thirty years, cleaned off his workbenches, had a

heart attack, and died two days later in a plain hospital bed.

Holding my father’s soft, mottled hand, I vainly wished him

a similar merciful death.

“Losing my—arm. W-w-w-ugh. W-w-ugh. W-w-w-w-ugh.

One thing,” my father said, gesturing, trapped in the prison of

his damaged speech. I understood: after a day or two in the army

field hospital in a state of suicidal despair, and after months

of rehabilitation, and countless nights drinking on the Rhodes

University campus with other wounded and demobilized veter-

ans, he’d picked himself up, abandoned his hoped-for career in

chemistry, reeducated himself as a historian, met and married

my mother, and made a good life.

“R-r-r-r-ugh. R-r-r-r-ugh. Rotator—.” He shrugged, and

again I understood. In his sixties, a tear in his rotator cuff,

repaired surgically without much benefit, had left him unable

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 50

1/31/13 12:27 PM

knocking on heaven’s door

51

to reach the salt across the table. But he’d adapted. He’d still

been my dear father Jeff.

“But

this,

” he said, looking me straight in the eye and shaking his head in puzzlement and outrage.

This

was different.

“This.”

Back at the house, I hung up his coat by the door. The hook was

too high for his now-limited reach, and my mother didn’t want to

move it down and spoil the clean lines of the vestibule. Upstairs

in the cold guest bedroom, I sat down at her old calligraphy

desk, pulling a blanket over my knees. My mind was still mov-

ing in conflicted ways: I hoped my father would die a natural

death; I wanted him to be as functional and happy as possible.

Running my finger down the numbers in the “physical therapy”

section of the Greater Hartford Yellow Pages, I found a physi-

cal therapist in nearby Cromwell with her own exercise pool

who accepted Medicare’s low reimbursement rates. I wrote the

number on an index card, handed it to my mother triumphantly,

and started packing my Rollaboard for California, thus setting

in motion a fix with devastating unforeseen consequences.

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 51

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 52

1/31/13 12:27 PM

II

Fast

Medicine

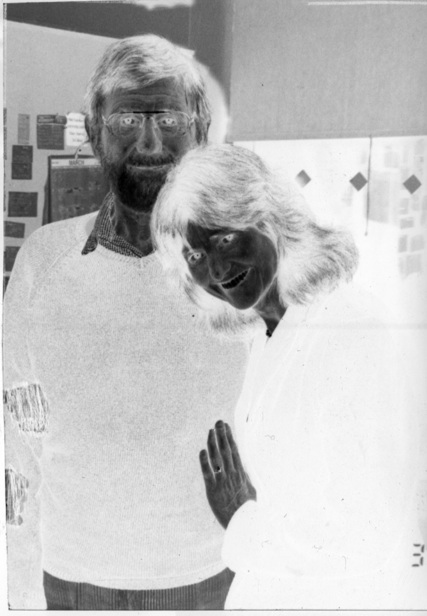

Jeffrey and Katy Butler

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 53

1/31/13 12:27 PM

KnockingHeaven_ARC.indd 54

1/31/13 12:27 PM

Fast Medicine

In early December, my mother called with news. The enthu-

siastic new physical therapist had sent my father through his

pool exercises so hard that two gaps had opened up in the smooth

muscle of his lower abdomen. Through those gaps nosed bits