Known and Unknown (48 page)

Authors: Donald Rumsfeld

I had no interest in using food as a weapon, and it was an oft-repeated admonition from President Bush that we should not do so. But it didn't make sense to me that American military personnel should risk their lives so food could be delivered to Taliban strongholds, especially when there were urgent needs for food in areas controlled by our Afghan allies. Some humanitarian organizations further argued that U.S. food aid paid for by U.S. taxpayers should not be identified as coming from the United States. Their contention was that America had a bad reputation and Afghans would react negatively if they knew the source of the food. Again, I disagreed. One purpose of the aid was to build goodwill among ordinary Afghans, so they would support our coalition's effort to liberate their country from the Taliban and al-Qaida. We even took pains to communicate to the Afghans that the food was fit for consumption according to Muslim religious law. I did not believe hungry people would refuse to eat food because it was known to come from the United States. And the humanitarian organizations provided no evidence that that was the case.

Some NGOs tried to ingratiate themselves with Taliban authorities by criticizing the actions of the U.S. military and our coalition partners in the press. But rarely, if ever, did I hear an organization complain publicly about the brutality of the Taliban or al-Qaida. At one point the Taliban raided the offices of a major international humanitarian organization, taking medical supplies and stripping the office bare. The organization did not say a word about it, presumably for fear of retaliation.

16

The same organization freely publicized its complaints about the United States.

Â

T

hroughout the twelve days of the bombing campaign, members of the Northern Alliance questioned whether we were being effective. Targeting the Taliban and al-Qaida required information and tactics that only our special operations forces could provide for precision air strikes. Without the coordination of our laser targeting against the key Taliban and al-Qaida emplacements, Afghan commanders were reluctant to go on the offensive.

Meanwhile, at the Pentagon, we waited anxiously for CIA and special operations teams to link up with Northern Alliance commanders and the Pashtun opposition leaders in the east and south. At K-2 in Uzbekistan, the Army Special Forces A-Teams under the command of Colonel John Mulholland also waited for the signal to move. The special operators were champing at the bit, ready for their assignment as “the tip of the spear.” But the signal to deploy into Afghanistan was not forthcoming.

The press was impatient as well. Once combat operations began, I received variations on the same question from Pentagon reporters: When would American ground forces be deployed? I counseled patience. Wars have their own tempo, I said. “Patience” was a proper theme, and I invoked it sincerely, even though I knew I often lacked that quality myself.

17

By mid-October, communications by satellite phone had been established with several Northern Alliance commanders, but only one CIA team had managed to connect with them on the ground. Code-named Jawbreaker, the team had linked up with General Fahim Khan, Massoud's successor and the de facto leader of the Northern Alliance. The delays in teaming up with the other Northern Alliance commanders were excruciating for me.

“My goodness, Tommy,” I repeatedly said to Franks. “The Department of Defense is many times bigger than the CIA, and yet we are sitting here like little birds in a nest, waiting for someone to drop food in our mouths.” It seemed we couldn't do anything until the Agency gave us a morsel of intelligence or established the first links on the ground.

In truth, the frustration extended well beyond Tommy Franks. In the month after 9/11, I had been continually disappointed that the military had been unable to provide the President with military options to strike and disrupt the terrorist networks that were planning still more attacks. In one memo to Chairman Myers and Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, Marine General Peter Pace, I wrote that “for a month, DoD has produced next to no actionable suggestions as to how we can assist in applying the urgently needed pressure other than cruise missiles and bombs.” My October 10, 2001, memo continued:

I am seeing nothing that is thoughtful, creative or actionable. How can that be?â¦The Department of Justice and its counterparts in other nations have arrested hundreds of suspects. The Department of the Treasury and its counterparts in other nations have frozen hundreds of bank accounts totaling hundreds of millions of dollars. The Department of State has organized many dozens of nations in support. But DoD has come up with a goose eggâ¦.

You must figure out a way for us to get this job done. You must find out what in the world the problem is and why DoD is such a persistent and unacceptably dry wellâ¦. We are not doing our jobs. We owe it to the country to get this accomplishedâand fast. Your job is to get me military options. It is the [President's and my] job to balance risks and benefits. We cannot do our job unless you do your job. If we delay longer, more Americans could be killed. Let's get it done.

18

Myers and Pace pushed all of the combatant commanders to come up with more options. In Afghanistan, Franks explained that there were factors outside anyone's control contributing to the delays. Blinding dust storms and white-out conditions in the high mountain passes had forced several teams to turn back. The CIA and CENTCOM were trying to use several older Soviet helicopters, similar to those the Taliban had in its possession, to fool the Taliban. But the old Soviet choppers were unreliable and not well suited for the weather conditions.

After one particularly long day in the first week of October, Franks called. The distress over the delays, expressed by everyone he was talking to in the chain of command from the President on down, was wearing on him. Franks questioned whether I still had confidence in him and asked if I thought the President should select a different commander. I admitted that the waiting was difficult but assured him flat out that he and his operation had our full confidence.

Â

I

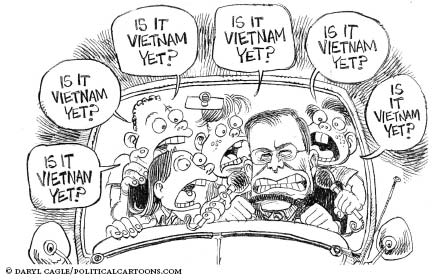

had to keep reminding myself that we were still only a few days into this campaign. Meanwhile, critics of the administration were plunging into despair. Some in the press, reflecting the concerns they were hearing, resurrected the word “quagmire,” an echo of the bitter domestic opposition to the Vietnam War. On September 18, seven days after 9/11 and one month before the first special operations teams would even enter Afghanistan, the Associated Press reported, “Now it may be the United States' turn to try a foray into the Afghan quagmire.”

19

A later editorial in the Dallas Morning News read, “[A]nother generation of American servicemen may be sucked into a quagmire in a foreign land.”

20

“Are we quagmiring ourselves again?” the columnist Maureen Dowd asked two days later.

21

R. W. Apple, a well-respected foreign correspondent, opined on the front page of the New York Times, “Like an unwelcome specter from an unhappy past, the ominous word âquagmire' has begun to haunt conversations among government officials and students of foreign policy, both here and abroad. Could Afghanistan become another Vietnam?”

22

At one press briefing after another, General Myers and I were asked why the military operations were not progressing faster. I believed it was my job to urge CENTCOM to move forward as quickly as possible, and I did so in private. But much of the public discussion, especially the growing quagmire chorus, lacked restraint and historical perspective.

I usually enjoyed my exchanges with the Pentagon press corps. There were several dozen reporters who were regularly assigned to the Pentagon beat. They had small offices not far from the room where we gave media briefings. Most were knowledgeable, hardworking, and reasonably objective, though often skeptical. Many had been in the Pentagon when American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the building. I was sympathetic to them. Some periodically said that they had to cope with guidance from their editors, who knew that playing up a potential disaster is what sold. As the saying goes, “If it bleeds, it leads.”

I often injected humor into our exchanges with journalists. It's a relief to find occasion to lighten the mood when discussing serious matters. At one point, our press conferences were parodied on the television show

Saturday Night Live

. I remembered the show for its spoofs of President Ford in the 1970s that did him real political damage. Still, I had to admit that the skits of my press conferencesâwith comedian Darrell Hammond playing my bespectacled selfâwere amusing.

Over the years I had seen many times what happens in politics when a public figure receives a good deal of media attention. Journalists rely heavily on standard narratives that both conform to and shape the conventional wisdom about government officials. If one starts with “good press,” one often gets more and more favorable coverage; early bad stories often spawn additional negative reporting. But journalists also relish dramatic reversals. One memorable observation in this regard was made by World War II general Joseph Stilwell, who warned, “The higher a monkey climbs, the more you see of his behind.”

Still, a free nation could not survive without a free press and an open, transparent government. It was what we were fighting for against our enemies.

23

I felt an obligation to explain to the American people in press conferences what the Defense Department sought to achieve in Afghanistan and what was happening on the ground there.

Kabul Falls, Karzai Rises

O

n October 19, the first of our Special Forces A-Teams made it into Afghanistan, and the twelve men successfully linked up with the ethnic Uzbek warlord General Abdul Rashid Dostum south of Mazar-e-Sharif. Later that day, two hundred U.S. Army Rangers descended onto a dusty airstrip designated Objective Rhino in southern Afghanistan.

1

Franks had learned of the airstrip from Sheikh Muhammed bin Zayed, military chief of staff of the United Arab Emirates, who had outfitted the remote location as a camp for hunting with falcons in the surrounding hills.

2

Rhino was strategically positioned between Kandahar and the Pakistani borderâan ideal place from which to attack enemy terrorists trying to flee Afghanistan and seek sanctuary in Pakistan's tribal regions. CENTCOM broadcast to the world the greenish night-vision images of the seizure of Rhino, demonstrating that the U.S. military was moving into Afghanistan.

In the south our forces raided deep into Taliban-controlled territory. Near Kandahar, they launched an attack on one of the compounds of Taliban leader Mullah Omar. They began to call in supplies to be delivered by airâfood, medical assistance, and ammunitionâas well as the massive firepower of U.S. Air Force and Navy aircraft. Members of the A-Teams served as forward air controllers, using laser range finders and GPS technology to pinpoint targets for devastatingly accurate air strikes. By the beginning of November the Taliban front lines in the north were being bombarded with two-thousand-pound Joint Direct Attack Munitions (JDAM) and an occasional fifteen-thousand-pound BLU-82 Daisy Cutter, then the most powerful non-nuclear weapon in our arsenal. The Taliban lines were also attacked by U.S. Air Force AC-130 gunships, an aircraft with 105 millimeter howitzers, 40 millimeter cannons, and 25 millimeter Gatling guns able to fire an intimidating eighteen hundred rounds a minute. Intelligence sources reported that the gunships' withering fire was particularly devastating to enemy morale. Our special operations forces were spotting Taliban fighters on ridgelines and calling in close air support to attack them.

On November 5, the forces under Northern Alliance commander General Dostumâoutnumbered by the Taliban by eight to oneâbegan their assault on Mazar-e-Sharif, the largest city in northern Afghanistan. Capturing Mazar was a crucial objective because it would open a land bridge from Uzbekistan, which was valuable for resupply efforts, particularly during the critical winter months.

3

At first Mazar's walls protected the Taliban's artillery units and antiaircraft missiles. But from the surrounding hills, special operators spotted major Taliban units and targeted them with air strikes. Four days after the assault began Afghan and American forces, some on horseback, rode into the heart of the city, cutting off the Taliban, capturing Mazar, and sending the first major signal to the Afghan people and the world that the Taliban could be defeated.

Meanwhile, General Fahim Khan's troops moved to seize the northern cities of Taloqan and Kunduz. General Ismail Khan captured Herat in the west. Pashtun forces were marching toward Kandahar. The ingenuity of American special operators and CIA teams, combined with precision U.S. airpower and the grit of Northern Alliance troops, forced Taliban fighters to retreat to the south. The quagmire talk began to die down, at least for the moment.

Â

A

s the northern cities began to fall, I made another trip to meet with Afghanistan's neighbors.

4

My first stop in Russia attracted the most attention and had the potential to be the most uncomfortable. The country's disastrous decade-long occupation of Afghanistan still rankled. A speedy military victory by American forces would be another embarrassment. Perhaps for this reason President Putin refused to allow the United States to move military equipment through Russian territory and sought to constrain our developing relationships with the neighboring former Soviet republics.

After meeting with Defense Minister Ivanov, reporters pressed him about whether Russians troops were going to join the coalition effort in Afghanistan. “I am asked this every day,” Ivanov replied, “and every day I say no.”

5

I agreed privately, knowing that Russian troops reentering Afghanistan would not be greeted as liberators.

At the close of the Ivanov meeting, I was escorted to the gilded rooms of the Kremlin for a meeting with President Putin. He spoke without pause for close to ninety minutes. He was, as usual, somewhat of an enigma. Though he denied us tangible assistance for the Afghan effort, he was generous with his adviceâwhich Afghans we could trust, the motives of regional playersâright down to military tactics. He also pushed for the United States to buy Russian military equipment for Afghan Northern Alliance commanders. He declared without any sense of irony that the Afghans were very familiar with Russian equipment.

From Russia I traveled to Pakistan and then India. Both nations had had poor relations with the United States prior to the Bush administration. Our military had had next to no contact with Pakistani forces for a decade because of an American law that barred military support or training to Pakistan unless the U.S. government certified that Pakistan was not producing a nuclear weapon. Because of this congressional ban, a generation of Pakistani military officers had no ties to their American counterparts, which had spawned mistrust and bad feelings.

Yet in 9/11's aftermath, the United States was able to develop an increasingly constructive partnership with Pakistan. Powell and his State Department colleagues had begun to persuade President Pervez Musharraf that he needed to cast his lot either with the United States or the Taliban and the Islamist extremists his country had backed for years. When he saw that America intended to act forcefully after 9/11, Musharraf chose the United States. Other Pakistani officials, however, hedged their bets by retaining ties with the Taliban and various terrorist groups that operated against India.

Musharraf was a gracious host. Though he was clearly in charge of his government, he had enough confidence to let his advisers speak freely in meetingsâsomething that was unusual in that region. He was forthright about his domestic constraints, and he warned that the United States needed to do a better job combating enemy propaganda in the Muslim worldâa crucial objective that should have been a top priority for the Bush administration over the years to come, but which to our lasting disadvantage was not.

Our country's relations with India also improved dramatically under the Bush administration.

6

The United States had all but shunned India after its 1998 nuclear weapon test.

7

But from the earliest days of the administration, I believed Indiaâthe world's most populous democracyâwas going to be of strategic importance. I did not think it made any sense for us to be at odds with them. In February 2001, only fourteen days after I took office as secretary of defense, I sought out a bilateral meeting with the Indian national security adviser, Brajesh Mishra, at a security conference in Munich, to make this point. President Bush was ready to make ties with India a priority for his adminis tration.

Despite the cordial welcome, my meetings with Afghanistan's various neighbors left me with misgivings. The region was a maelstrom of suspicion and intrigues. Pakistan distrusted the Northern Alliance. India distrusted Pakistan and vice versa. Russia distrusted our relations with its neighbors. And nearly everyone distrusted the Russians. Each of the countries surrounding Afghanistanâespecially the one country I did not visit, Iranâseemed prepared to jockey for influence with whatever government arose and ready to use their longtime connections in that country as proxies. Stabilityâmuch less democracyâwould be difficult to bring to an impoverished country that had for decades known little more than civil war, occupation, drought, drug trafficking, warlords, and religious extremism.

On the long flight back to the United States, I spoke to President Bush over a secure phone. “Afghanistan risks becoming a swamp for the United States,” I told Bush, using the word I once used when I was President Reagan's envoy to the Middle East. “Everyone in Afghanistan has an agenda or two. We're not going to find a lot of straight shooters.”

Bush expressed optimism about our efforts there. But I was not optimistic about the country's ethnic groups coming together and sharing power. “It's my view we need to limit our mission to getting the terrorists who find their way to Afghanistan,” I advised the President. “We ought not to make a career out of transforming Afghanistan.”

8

Â

O

nce American special operations forces were on the ground in Afghanistan, territory began to fall to our Afghan allies more quickly than we had imagined possible. By early November, Northern Alliance troops had advanced to the outskirts of Kabul, and were poised to take the capital city. At this point, the months-long discussions within the administration over what to do with the Taliban came to a head. State Department and CIA officials again expressed concern about the prospect of Northern Alliance troops seizing the capital city. Tenet reported that his intelligence experts were concerned that some Pashtun tribes in the south with historic ties to Pakistan and the CIA would be offended if the country's capital was taken and occupied by Northern Alliance forces.

I supported the Northern Alliance's advance into Kabul for a simple reason: It was the only realistic option. The Northern Alliance leaders had no intention of letting their enemies in the Taliban hold on to Kabul while they had the advantage.

9

Furthermore, as a practical matter, the few dozen U.S. special operators embedded with the Northern Alliance probably would not have been able to stop their advance even if we wanted them to.

Even as the issue was still being discussed in the National Security Council, reports surfaced in the press that Powell and Rice were saying the United States was not going to advance on Kabul. Their comments concerned me, given the position I thought the President had set out clearly in speeches about removing the Taliban.

*

On November 13, I sent a memo to Bush, copying Powell, Rice, and Tenet. “Mr. President, I think it is a mistake for the United States to be saying we are not going to attack Kabul,” I wrote. “To do so, tells the Taliban and the Al Qaida that Kabul can be a safe haven for them. The goal in this conflict is to make life complicated for the Taliban and the Al Qaida, not to make it simple.” I also made the point that if we wanted to open the routes to the south, where al-Qaida and the Taliban still roamed with relative ease, we would need to control the capital city. “It is one thing to not take Kabul,” I added. “It is quite another to announce to the world that we are not going to take Kabul. I have read that Condi and Colin have both been saying this. I don't believe anyone talked to me or Tommy Franks about the concept of doing that. I think it is a bad idea.”

11

Not waiting for Washington to decide, the Northern Alliance forces marched on Kabul on their own initiative. In a desperate broadcast to his fleeing troops, Taliban leader Mullah Omar reportedly warned them to stop “behaving like chickens.” It was to no avail. When Northern Alliance forces first set foot in the city, on November 13, 2001, they met little resistance. All that remained of the Taliban's defenders in their former seat of power was a group of a dozen or so fighters hiding out in a city park. Just five weeks after our air strikes had begun, Afghanistan's capital city was under the control of Northern Alliance forces. I was relieved. When I conveyed the news to the President, he was eager to see the offensive continue.

Soon anti-Taliban forces gained control of many areas in eastern Afghanistan, including the city of Jalalabad that straddled the important route leading to the Khyber Pass and Pakistan. Al-Qaida leader Mohammad Atef, a deputy to bin Laden, was killed in an air strike. The remaining Taliban forces were being driven farther and farther south, toward Kandahar, a city of some three hundred thousand people that had become a way station for the most hard-core enemy fighters. There the Taliban would make its stand. A small contingent of U.S. Marines, under the command of a gruff and brilliant warrior, Brigadier General James Mattis, bolstered our presence in southern Afghanistan. The focus of the campaign now turned to an Afghan fighter who would be charged with taking Kandahar.

Though he had the demeanor of a polished, urbane, and scholarly gentleman, Hamid Karzai was tough and tenacious and seemed to command respect from diverse quarters of Afghan society. The day after the American bombing of the Taliban began, he crossed the border into Afghanistan from Pakistan on a motorcycle, where he helped organize anti-Taliban forces in the country's south. A Pashtun tribal leader from a prestigious clan, he commanded a small cadre of Pashtun troops.

*

In an early skirmish, a bomb dropped from a B-52 had sent shrapnel and debris in his direction, slightly wounding him in the face.

12

Karzai and his forces reached Kandahar on December 7. Contrary to expectations, the city fell quickly. The Taliban apparently knew that they could not win, so they had decided to regroup to fight another day.

By early December, two months to the day since the start of our combat operations, the Taliban had been pushed out of every major city in Afghanistan. By any measure, it was an impressive military success. Estimates varied, but likely some eight thousand to twelve thousand Taliban and al-Qaida fighters were killedâand hundreds more were captured. Eleven U.S. servicemen had given their lives, and another thirty-five had been wounded in this initial campaign against al-Qaida and the Taliban.