Knuckler (22 page)

Authors: Tim Wakefield

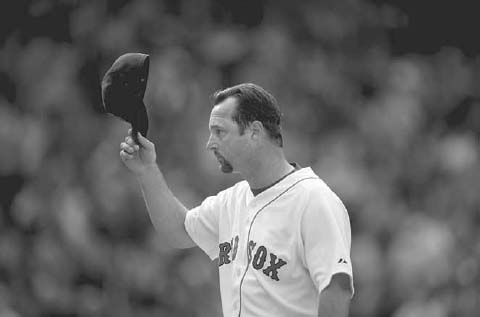

Paul Keleher / Flickr Unreleased / Getty Images

FINALLY, AN ALL-STAR: Just before Wakefield's forty-third birthday in 2009, Tampa Bay Rays manager Joe Maddon selected Wakefield for his pitching staff to represent the American League in the 2009 All-Star Game. Wakefield joined (from left to right) closer Jonathan Papelbon, starter Josh Beckett, first baseman Kevin Youkilis, and left fielder Jason Bay at the game.

Michael Ivins / Boston Red Sox

TEAM PLAYER: Wakefield and his wife, Stacy, have continued the pitcher's charitable endeavors throughout his time in Boston. In 2010, Wakefield was awarded the prestigious Roberto Clemente Award for his contributions to baseball on and off the field.

Julie Cordiero / Boston Red Sox

LOYAL TO THE END: At the conclusion of the 2010 season, Wakefield was among a most select group of active major league players to have spent fifteen or more seasons with one team. Entering 2011, he was a mere seven victories short of two hundred for his career.

Michael Ivins/Boston Red Sox

The knuckleball screws up the mind.

âFormer major league coach Tim Owens

A

T ONE OF

the darker and more disappointing moments of his Red Sox career, Tim Wakefield was blindsided. The Red Sox had just survived the 1999 American League Division Series with an emotional and draining comeback against the Cleveland Indians. They were delighted, but that hard-fought series had the team scrambling. And now they had the Yankees to face. Wakefield slept some on the team's flight from Cleveland to New York, but he was also busy wondering about his role in the next round of the playoffs.

The next day, seated at his locker at Yankee Stadium, Wakefield folded up his favorite section of

USA Today,

crossed his legs, and began working on the crossword puzzle as the team prepared for an off-day workout in anticipation of the rapidly approaching American League Championship Series. Wakefield had pitched twice in relief during the Indians series, but the outings were short. He was rested. And because the Red Sox pitching staff had been depleted during the Cleveland series, Wakefield believed that he was in prime position to aid the cause.

I wonder if they'll ask me to start Game 1.

Of course, Wakefield wanted to start Game 1, felt he deserved it, believed he could help. The Red Sox felt otherwise. Wakefield was still seated at his locker when he noticed manager Jimy Williams nervously walk by, avoiding eye contact, with no apparent destination.

That's

weird

. For several minutes, the manager kept walking back and forth in front of Wakefield's locker. Maybe his sometimes quirky manager, he thought, was merely burning off nervous energy following a series and trip that had left them all drained, exhausted, operating on fumes.

Then Williams finally stopped and abruptly invited Wakefield into the visiting manager's office at Yankee Stadium, where he asked Wakefield to sit as he shut the door.

At that instant, Williams also shut the door on Tim Wakefield's 1999 season.

Believing he was about to be named the Game 1 starter, Wakefield instead sat in disbelief as Williams informed him that he would be left off the active roster for the ALCS against New York. Wakefield was not merely bypassed for Game 1; he would not be pitching

at all.

He did not know what to say or do. He asked Williams for an explanation but never really got one, the manager instead mincing his words and talking in circles. Williams had arrived at the ballpark early that day, he told Wakefield, and had been in his office "stewing for two hours." Then he had walked into the clubhouse, repeatedly checking to see if Wakefield had arrived. After Wakefield showed up and settled into the chair in front of his locker, Williams found himself still unable to engage his pitcher.

The more Williams talked, the more Wakefield wondered,

Is Jimy really the one making this decision?

Two years earlier, Williams had stood his ground with regard to Steve Avery, but that was a different case. Williams had felt he was being told

how

to employ his pitcher, and

how

fell under the jurisdiction of the manager. For someone like Williams, in any organization, roles were clear. The general manager got the players. The manager implemented them. Problems arose when boundaries were not respected. But if Wakefield was being left off the playoff roster, that decision had to be coming from higher up. There had to be other factors influencing the outcome of an organizational discussion on the matter.

To Wakefield, his manager seemed unusually evasive. Williams danced around questions about the decision-making process and his role in them, all of which led Wakefield to believe that pitching coach

Joe Kerrigan was the one who had argued against his presence on the roster. An ally of general manager Dan Duquette, Kerrigan had that kind of power when it came to the pitching staff. It was entirely possible that in the organizational decision-making about the playoff roster, Williams was outnumbered and thus overruled. And so a frustrated, angry, and dejected Tim Wakefield got up from his seat and walked out of the manager's office, feeling as if Jimy Williams had delivered a message that he himself did not believe in.

This is unbelievable.

I can't believe this bullshit.

Indeed, to that point, there was no way Wakefield could have forecast such a demotion. The Red Sox were on a high in the wake of their victory over the Indians, a five-game affair in which the Red Sox had overcome a 2â0 series deficit and won the last three games, the final and decisive affair behind six brilliant relief innings from a wounded Martinez, who had strained his shoulder in Game 1. Wakefield had pitched twice in the series, including an effective outing in Game 2, and a second, less effective performance had been fraught with confusion. In the fifth inning of Game 4, after Rich Garces walked leadoff man Roberto Alomar in a game the Red Sox were leading 15â2, Wakefield had been ordered to start warming up. He had not had sufficient warm-up time when he was summoned into the game, but he said nothing. Wakefield then issued a pair of walks and two singles to the four batters he faced, trimming the Red Sox lead to 15â4 and prompting his removal from the game.

As it turned out, that outing had hurt Wakefield, at least in the eyes of Kerrigan. And so, after a season in which he did everything the Red Sox asked him to, Wakefield was undone by four batters in a lopsided affair during which he felt rushed into the game.

They put more weight on four batters I faced in a 15â2 game than they did on what I gave them during the regular season.

Even Williams clearly and obviously sensed the unfairness of it all. Wakefield finished the regular season with individual totals that hardly illustrated his contributions to the teamâa 6â11 record, a 5.08 ERA, and 15 saves in 140 innings pitchedâbut that was a trade that Williams

and others were willing to make because of the emphasis placed on the ninth inning. Late in the year, Williams had made it a point to highlight Wakefield's contributions and had focused far more on the group results than the individual ones because those were what mattered.

"I don't think there's been a pitcher in this era who has done the things Wakefield has done," said the knowledgeable manager.

And yet, now Wakefield was

out.

It made no sense to him.

Outraged, Wakefield returned to his locker at Yankee Stadium and later vanished into the more private areas of the visiting clubhouse, hoping to avoid reporters who undoubtedly would ask him about being slighted after the season of sacrifices he had just produced. When the media finally corralled him, Wakefield tersely declined comment. On the inside, he was angry and hurt, feeling that the team had deprived him of something he had dutifully earned. He wanted to go home and leave the team altogether, but teammates Mark Portugal and Rod Beck, both veteran pitchers, persuaded him to stay.

You're not the kind of guy who leaves. That's not who you are.

Wakefield watched the postseason from the dugout and the clubhouse, often wishing he were somewhere else throughout the balance of the postseason, a five-game series during which the Yankees rolled to a 4â1 series victory over Bostonâand eventually a third World Series title in four years.

While Boston's problems in the series were primarily on offenseâthe Red Sox scored a mere eight runs in the four losses and truly dominated only in Game 3, a 13â1 victory behind the otherworldly MartinezâWakefield believed that he could have helped. Still, that belief was causing only a fraction of his angst. Wakefield believed that the Red Sox owed him something, too, and he eventually became more convinced than ever that it was pitching coach Kerrigan who had undermined him. Following the '99 season, in a phone conversation with Wakefield, Williams suggested that the pitcher blame his manager for the slight at playoff time, but it was entirely within Williams's character to fall on his sword for the good of the team, just as the skipper had done in the manager's office at Yankee Stadium.

The more Wakefield thought about it, the more the pieces fit to

gether. Wakefield's status as a knuckleballer frequently left Kerrigan helpless, just as Niekro had predicted.

Managers and pitching coaches, they can't help you much with the knuckleball.

And when push came to shove, when it came time to give Wakefield the smallest measure of thanks for a season filled with sacrifice, the Red Sox replaced him on the playoff roster.

Wakefield had never once thought that the sacrifices he made during the regular season would hurt him with regard to his place on the playoff roster.

As it turned out, the entire series of events left a mark on his soul that extended well beyond October 1999.

By most accounts, Joe Kerrigan was a fairly judicious pitching coach and a student of the game, but one who lacked the people skills that might have made him more popular and possibly more effective. In the major leagues, pitching coaches are often psychologists. Most of the pitchers have indisputable ability. The coach's job is to tailor his methods to the specific needs of each player, to enhance strengths and cover weaknesses.

Kerrigan's level of tinkering often went too far, as happened with a young Japanese right-hander named Tomo Ohka, who had gone a combined 15â0 with a 2.31 ERA in the minor leagues during the 1999 season before being summoned to the major leagues. When the young pitcher's results did not similarly transfer immediately, Kerrigan began overhauling his mechanics, changing the way he did things. Veteran Sox players took note and shook their heads. Ohka finished 1â2 with a 6.23 ERA that season and ultimately fizzled out in Boston before winning 10 or more games in three separate seasons with other teams. While Ohka hardly became a superstar, there was a sentiment in the Boston organization at the time that Kerrigan had hurt Ohka more than he had helped him, largely because Kerrigan wanted Ohka to do things

his

way rather than utilize the talents and style that had helped him in the minor leagues.