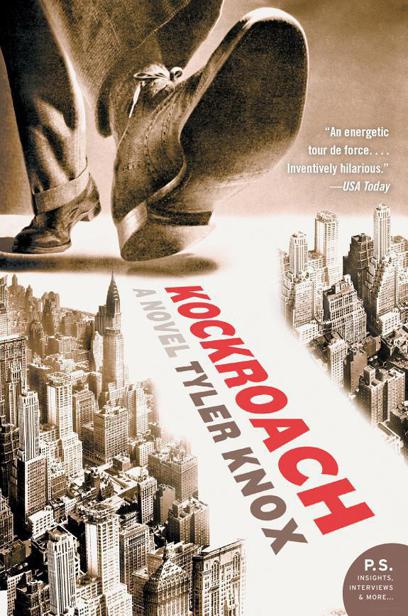

Kockroach

Tyler Knox

For G.S.

And for Mr. G.,

who introduced him to me

A story, for example, something that could never happen, an adventure. It would have to be beautiful and hard as steel and make people ashamed of their existence.

—J

EAN

-P

AUL

S

ARTRE,

La Nausée

As Kockroach, an arthropod of the genus Blatella and of…

They call me Mite. You got a problem with that?

The world, Kockroach discovers, is marvelously hospitable when your skin…

All right, I hears you. Enough with Mite’s weepy childhood.

Kockroach doesn’t question where the little man in the green…

Each night after work, as she poured the cream into…

Kockroach feels a surge of excitement roll through him as…

Was a geezer what hung around the Square name of…

Celia Singer stared down at the thick slab of beef…

Kockroach does not dream. The inner mechanisms of his brain…

If you took a midnight stroll in the Square in…

Kockroach waits patiently in the car. He has an inhuman…

Was one more player you needs to know about, missy,…

Within the hard brown exterior of the Lincoln, wedged in…

The train, it shivered as it pulled out of Penn…

Singed and smoldering, driven relentlessly by fear, Kockroach slithers through…

Kockroach moves now through the streets of the city in…

Eight years after, after it all went to hell, eight…

The night of Mite’s reappearance after eight long years, Celia…

Kockroach can feel it in his bones. Mite is close,…

Celia moved through the days after her visit to the…

Kockroach is ill at ease.

I suppose I gots a problem with saying goodbye.

As Celia Singer sewed the beads on the wedding dress,…

Kockroach stands at the center of his world. He can…

THE SWITCH

1

As Kockroach,

an arthropod of the genus

Blatella

and of the species

germanica,

awakens one morning from a typically dreamless sleep, he finds himself transformed into some large, vile creature.

He is lying flip side up atop a sagging pad. Four awkwardly articulated legs sprawl on either side of his extended thorax. His abdomen, which once made up the bulk of his body, lies like a flaccid worm between his legs. In the thin light his new body looks ridiculously narrow and soft, its skin beneath a pelt of hair as pale and shriveled as a molting nymph’s.

Maybe that is what has happened, maybe he has simply molted. He reflexively swallows air, expecting his abdomen to expand into its normal proud dimensions and the air to swell his body until the skin stretches taut so it can begin hardening to a comforting chocolate brown, but nothing happens. No matter how much air he swallows, his body remains this pale pathetic thing.

A flash of red rips through the crusts of Kockroach’s eyes before disappearing, and suddenly, in the frenzied grip of positive thigmotaxis, he wriggles his legs wildly until he tumbles onto the floor. With his legs beneath him now, he scurries under the wooden frame supporting the pad, squirming back and

forth, ignoring the pain in his joints, until he has found a comforting pressure on his chest, his back, his side.

Better, much better. The red light snap-crackles on, hissing and glowing throughout the room, slinking beneath the wooden frame before disappearing just as suddenly. It snap-crackles on and disappears again, on-off, on-off. His fear of the light subsides as the pattern emerges, when something else draws his attention.

A rhythmic rush of air, in and out, an ebb and flow coming from somewhere nearby. He turns his head, trying to find the sound’s source before he realizes that a peculiar undulation in his chest matches the rhythm of the rushing air.

Cockroaches don’t breathe, per se. Instead, air flows passively into openings called spiracles and slides gently through tracheae that encircle their bodies. There is the occasional squeezing of air from the tracheae, yes, but nothing like this relentless pumping of air in and out, in and out. It is terrifying and deafening and unremitting. It is so loud it must be drawing predators. Kockroach spreads his antennae to check his surroundings and senses nothing. He reaches up a claw to clean the receptors and gasps upon finding no antennae there. The sound arising from his throat is shockingly loud, a great anguished squeal that frightens him into silence.

His shock wanes as quickly as it waxed. He doesn’t wonder at how this grossly tragic transformation has happened to him. He doesn’t fret about the blinking light or gasping breath, about his pale shriveled skin or missing antennae. Cockroaches don’t dwell in the past. Firmly entrenched in the present tense, they are awesome coping machines. When his

right leg was pulled off by a playful mouse, he hadn’t rolled over and whined, he had scampered away and learned to limp on five legs until he grew a new limb with his next molt. Deal with it, that is the cockroach way. When food is scarce, cockroaches don’t complain, first they eat their dead, then they eat their young, then they eat each other.

Kockroach blinks his eyes at the growing brightness in the room. He is tired already. He is used to two bouts of feverish activity in the middle of the night and then a long sleep during the day. The dawn light signals him it is time to retire. Pressed against the edge of the wall, his aching limbs jerk beneath him, his back rises to touch the slats of the wooden frame, and he falls asleep.

When Kockroach awakens again it is dark except for the rhythmic pulse of the hissing red light. He is still wedged beneath the wooden frame. His four legs now ache considerably and a line of pain runs through his back.

From beneath the frame he can just make out the contours of the room, its walls and baseboards veined by inviting little cracks. There is a wooden object in the middle of the room, and beside it, floating above the floor, is a piece of meat, the top of which is obscured by the top of the frame.

Kockroach crawls quickly out from under the wooden frame, stops, crawls quickly again, dashes beneath the meat, heads for a lovely little crack he espied from afar. He dives into it and bangs his head on the wall.

He had forgotten for a moment what had happened to him.

Slowly he brings his face down to the crack that seems now so small. In the recess he sees two antennae floating gracefully back and forth. He reaches to the crack, tries to place his claw in the crevice to touch his fellow arthropod. His digits splay, the claw screams in pain. He articulates the digits, five of them, one by one before his face. What a grotesquely useless configuration. He reaches out one digit and guides it to the crack. Only the slightest bit of soft flesh slips in.

Suddenly, he is overwhelmed by a thousand different sensations that seem strangely more real than his bizarre altered presence in that room. The patter of hundreds of feet, the crush of bodies, the blissful stink of the colony. The feel of his antennae rubbing against the antennae of another, pheromones bringing everything to a fever pitch, being mounted from behind, his hooks grabbing hold. The taste of sugar, starch, the desperate run across a patch of open light. He is slipping back through his life. The shedding of old chitin, the taste of it afterward, the delicious feel of his mother’s chest upon his back when he was still the smallest nymph. He slides his digit back and forth along the crack in the wall and falls into a pool of remembrance and emotion, both stunning and unexpected.

But sentimental nostalgia is not a cockroach trait, neither is regret, nor deep unsatisfied longing. He had never felt such sensations before and he fights against their unfathomable power with all his strength. Insectile resolve battles mammalian sentimentality for supremacy over this new body until, with a great shout, Kockroach triumphantly climbs out of the strange emotional swirl and falls back into himself.

He won’t let this strange molt ruin him. He will stay true

to the purity of the instincts that have guided him safely through the earlier stages of his life. Whatever has happened, whatever will happen in the future, he will forever remain a cockroach.

He traces his digit up the wall, as if the tip itself is an arthropod making its way to the safety of the ceiling. Halfway to the top his claw alights on a dull white plate with a black switch. Cockroaches instinctively try every crevice, search every nook, climb every tilting pile of dishes. It is in their nature to explore. He flicks the switch.

Light floods the room. Panic. He would flee, but to where? He follows his second instinct to hide against a wall and freeze. He spins and presses himself into the corner and moves not a muscle.

He listens for the sound of a predator and hears nothing.

He presses his head so hard into the corner the vertex of his face throbs.

Still nothing.

With a start, he realizes he is standing and the ache he had been feeling in his legs, the pain in his back, are all slowly receding. This is a body that works best vertically. He will adapt, he is a cockroach.

Balancing precariously on two pale slabs of flesh at the bottom of his lower legs, he takes tiny steps as he turns around, his upper legs moving contrapuntally with his lower legs out of long-ingrained habit. And as he turns he examines the now-lit space in which he finds himself. It is in actuality

a small pathetic hotel room, green walls that can barely contain a bed and a bureau and a tiny desk, a single window through which the hissing red neon of the hotel’s sign can be spied; it is a sad cramped piece of real estate but to Kockroach it is a palace. And in the center, hanging from the source of light, is the piece of meat.

Kockroach is frightened when he sees it there, shaped as it is like a predator, but it is just hanging, not moving, hanging. He determines it is not a threat and his fear subsides.

Still in the corner, he reaches out his upper appendage, an arm now that he is standing vertically, and with his claw flicks down the black switch on the white plate. Darkness.

He flicks it up. Light.

He flicks it down. Darkness.

So that is how they do it.

Up and down, up and down. After an hour of that he leaves the light on and practices walking.

He falls twice, thrice, six times, struggling to stand again after each fall. He is trying to retain the feel of his cockroach walk, when his legs moved forward three at a time while the other three maintained a steady tripod, allowing for sudden stops and quick switches of directions. This body is not so nimble or steady, the center of gravity is absurdly high, but finally, after much trial and error, he comes up with something that feels organic.

He leans back, his weight to the right as he steps forward with his left leg, his right arm rising reflexively with the step,

two digits of his right claw pointing up in the shape of a V, like the pincers of the cockroach claw. Then his weight shifts to the left as his right leg steps, left arm rising, two digits of his left claw shaping the V. Back and forth, rhythmic and steady, it becomes a natural movement as he circles the room, first one way, then the other, covering great gulps of distance with each step, stepping over and back, over and again, until it is mastered.

It isn’t long before Kockroach wonders how he ever before crawled on his belly or why.

With his walk in place, Kockroach explores. The bed, the bureau, the small desk covered with bizarre fetishistic objects. He takes in the color, size, the shape of these things, without knowing their purposes or names. There is a door he can’t open with all manner of metal running down its side, there is an open door leading to a cozy dark little room with cloths hanging from a rod, and there is another open door leading to another small room, slippery and cold, hard tile covering the floor.

In this room there is a large white seat that seems to fit his new proportions. In his many journeys he had seen seats like this before, in rooms much like this one, and from hiding places in baseboard cracks he had seen creatures sit on these white seats and let out horrible groans that had terrified him. It must be something dangerous, something awful, something truly bestial. Perfect reasons for a cockroach to try it.

He sits and groans, the sound rising, reverberating in the

tiny room, and he feels something, something not entirely unpleasant, causing him to groan ever more loudly. Cockroaches release desiccated pellets which grind as they are forced from the gut through the anus, but this, this is wet and slippery and strangely lovely. And the smell, the smell to a cockroach is ambrosial.

He groans again, louder, lets it out, tries for more, but it is over. There is nothing left. Maybe if he sits on that special seat long enough he can do it again. And again.

But what is that over there? A basin, with a strange panel atop it. He rises from the seat, steps to it. There is a single silver thing sticking out of the basin. He fiddles with it and cold water starts leaking out. He leans over and latches his mandibles around the thing to capture the water until it feels like his gut will burst apart. When he stands straight again what he sees in the panel above the basin sends him backing away with a shriek.

A predator face, staring at him, backing away as he backs away.

He approaches the panel again and stares at it. The face stares back. He tilts his head. The face tilts the same way. He reaches up a claw, points a digit to the face, and the other points a digit back. Kockroach moves his digit closer, closer, and so does the other, until just when their claws are about to touch they reach a barrier.

Twenty minutes later, after realizing that the other is himself and that the face staring back at him is now his own, he examines himself critically. The eyes are tiny and set low, there is a strange protuberance, like a beak, sticking out of the

middle of the face, and short bristly hairs cover the bottom half, surrounding a thin wide rictus, the mandibles bizarrely set horizontally and lined with ghastly white teeth. It is horrifyingly ugly, with none of the sharp elegance of a cockroach face. Where are the huge black eyes? Where are the antennae? Where is the smooth lovely frons or the two sets of articulated palpi used to grind and test his food? This face he has now is both hideous and nearly useless.

As he stares in horror, the extent of the disaster that has befallen him slowly becomes manifest. He has become, of all things, a human.

Then he remembers where he saw before a face just like his new face: on the long piece of meat hanging from the ceiling.

He returns to the main room and circles the hanging thing with the exact same face as his own. It is a human, as is Kockroach now, naked, as is Kockroach now. A rope is fitted around the human’s narrow prothorax and tied to a fixture overhead. Maybe all humans have the same face, he considers, unlike cockroaches with their infinite differences. The eyes of the human are closed, the hypopharynx is purple and hanging thickly from the mouth. He pushes the hanging human and jumps back, but there is no reaction other than a slow swaying.

Kockroach knows dead and this is it.

A sound erupts from his abdomen. Kockroach spins, scared. The sound comes again and with it he can feel a vibration and suddenly he is certain that it is time to eat.

How can he be so certain?

Because, for a cockroach, it is always time to eat.

Kockroach searches the apartment for food, pulls out drawers, inspects the room with the cloths, the room with the seat. There are the brown lumps in the bowl of the great white seat, but that is feces, he knows, and even cockroaches won’t stoop so low as to eat their own feces, though the feces of other species are often a culinary treat.

In the desk he finds a thick black thing with shiny gold edges. He used to eat such things, used to delight in the tasty gobs of pale paste oozing from the back. He tries to gnash the thing in his teeth but his mandibles aren’t strong enough. He splits it open and rips out a thin individual leaf with its black markings, stuffs it in his mouth. He chews and chews until it is soft enough to swallow. He leans down, throws it up on the floor, sucks it up and swallows it again. He still is hungry but he doesn’t want to eat another leaf.