Kokoda (29 page)

Over the previous few days, the commanding officer of the men on the ground in New Guinea, Colonel Yosuke Yokoyama, had sent rather gloomy reports back to Rabaul that building a road was going to take a lot more resources and forces than had been planned. A later report of the campaign, which was secured and translated by a special section of the Australian Army, also indicated some dismay from the Japanese military commanders on the ground that things were not quite as they had expected…

‘As the rivers shown on aerial photographs were narrow, it was estimated that they would be easily crossed. However, these mountainous areas have steep inclines and generally speaking, in this locality the velocity of a stream is surprisingly great. Although the surface appears calm, drowning will occur in the rapid undercurrent.’

And again… ‘Although New Guinea is listed as a place with little water, the fact is that there is such a large quantity of water that it causes trouble.’

113

But despite the unexpected difficulties, the Japanese kept pushing south.

So this was Kokoda. And he was on the ground at last, after an aborted landing attempt the previous day. Commanding Officer of the 39th Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Owen, stepped out of the flimsy aircraft on the late afternoon of 24 July 1942 with a great sense of relief. He had been following scattered reports about his men and the Japanese incursions and been excruciatingly aware that there was nothing he could do for them back in Moresby. His rightful place as commanding officer, he had quickly decided, was to be commanding them in

battle

. On the track. So let’s get to it.

When the Lieutenant Colonel stepped down from the plane, Sam Templeton was waiting for him and within minutes the two were making their way forward to the Gorari ambush site, Templeton briefing Owen as they went. Neither man was in any doubt that this small outpost of Kokoda, with the only airfield within four days march in any direction, would be the key strategic possession in this campaign.

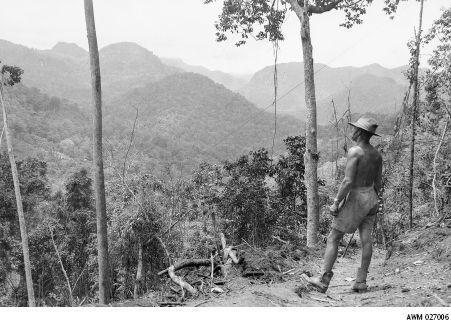

Nestled in the Yodda Valley beside the Mambare River, the village itself was perched on a neat plateau that was surrounded by the rubber trees of a large plantation. The plateau sat some forty feet higher than the valley floor in the break in the mountains known as the ‘Kokoda Gap’, and therein lay something of a story…

For on both the Australian and Japanese sides of the campaign there had been great confusion as to just what kind of topography would be described by the name ‘Kokoda Gap’. Initially, it was thought that to be a gap, as opposed to, say, a valley, it would have to be a singularly narrow aperture in an otherwise solid wall of mountains. For the more educated of soldiers, and more particularly some of the officers back at GHQ, there was talk of the Kokoda Gap perhaps being like the famous battle of ancient Greece which occurred at Thermopylae in 480 BC, where in a very tight mountain pass a small, heavily outnumbered Greek force was able to hold off the enormous invading Persian army. On a battlefield where there could be no flanking movements, all that counted was that your frontline troops be more powerful than the men they faced and there could be no limit to the number that they would kill.

But could the Kokoda Gap really be like that? Not one little bit. For when Lieutenant Colonel Owen looked around he was amazed— just as all new arrivals are amazed—to find that the famed Kokoda Gap was ten miles wide! If this was a mere gap, they’d hate to see what one of New Guinea’s wide valleys looked like. Maybe the gap was on the other side of the first hill, into the Owen Stanley Range proper. Somehow, because of the name bestowed on this geographical feature, they had all felt it must be in at least rough proximity to Kokoda village itself. For now though, Lieutenant Colonel Owen kept walking in the opposite direction, eager to be with his men as they set up for the next crucial confrontation.

It was a mark of Owen’s stamina that after he and Templeton arrived in Gorari at 2.00 a.m., the Lieutenant Colonel spent a couple of hours reconnoitring the terrain in the moonlight and consulting his commanders. And then, after he had rearranged their defences to his satisfaction—with his best men taking the brunt of the likely fire and the native battalions protecting the flanks—he set off immediately back to Kokoda to organise the small force there in similar fashion and hopefully receive fresh troops by air.

With the sun high in the sky on 25 July, the Japanese were suddenly sighted on the approaches to the Australian ambush position at Gorari.

Ssssssssssssssst

. The Australians knew that the thing with an ambush was of course to effect total surprise, but on this occasion it was a close-run thing. For just as the first of the Japanese troops were moving into the desired position, one of them saw a bush move ahead and shouted a warning to his comrades. Within a second the Japanese troops had dived for cover, expecting a volley of shots.

On the Australian side, however, there was no movement. Total discipline. While their every strained breath in the stillness sounded to their own ears like the shrill whistle of a steam train, their best hope remained that the Japs would regain confidence that there was no one waiting for them and would then move back on to the track.

And so it proved. From behind the thick foliage, the Australian troops kept their guns trained and through their sights they saw the Japs slowly get back on the track, led by the sheepish scout who had shouted the first warning and was now gazing right at the bush he had seen move. Within a minute a whole column of Japanese soldiers was making its way forward until it was almost on top of the Australians.

The man behind the Lewis gun, Arthur Swords, was sweating more than most. He was in a forward position and the Japanese lead scout was right upon him, looking, it seemed, right at him— much as Arthur was looking right down the barrel of the Jap’s gun—and it was all he could do to follow the order not to fire.

Hail Mary, full of grace, the Lord is with thee.

Blessed art thou among women, and blessed is the fruit of thy womb, Jesus. Holy Mary, mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death…

NOW! Lieutenant Harry Mortimore effectively gave the order by firing the first shot and, as one, the Australian troops opened up, killing or at least seriously wounding some fifteen Japanese soldiers before the rest had recovered themselves and were returning withering fire. Because the ambush site had been so well chosen, the Australians kept the Japanese pinned down for four hours. But from the moment the Japs began their flanking movements, all knew that every minute the Australians remained was another minute to their disadvantage, so Lieutenant Mortimore gave the order to retreat. In mere minutes the men born beneath the Southern Cross melted away to the next prepared ambush site at Oivi, some two hours walk towards Kokoda.

That night, apprised by radio of what had happened, Lieutenant Colonel Owen managed to get a message to Moresby: ‘Clashed at Gorari, and inflicted approx 15 casualties at noon. 5 p.m. our position was heavily engaged, and tired platoons are now at Oivi. Third platoon now at Kokoda is moving to Oivi at 6 a.m. Must have more troops, otherwise there is nobody between Oivi and Dean, who is three days out of Ilolo. Must have two fresh companies to avoid being outflanked at Oivi. Advise me before 3 a.m. if airborne troops not available.’

At the time that Owen’s message was received at Port Moresby, there was only one troop-carrying plane available—a Douglas DC3— but at least it was cranked up. Alas, there simply weren’t ‘two fresh companies’ able to go at such short notice, and the best that could be managed was 16 Platoon, comprising some thirty men, commanded by Lieutenant Doug McClean. Given that the maximum the plane could carry at a time was just fifteen men, McClean went forward with the first half of the platoon. As they crossed the Owen Stanley Range, many of the soldiers were caught between wonder at their first time in an aeroplane, relief that they did not have to cover on foot the thickly covered ridges and valleys, and great trepidation at what might await them when they landed. Though they had been told very little, the speed with which they had been called up told them that their boys were in trouble up ahead…

And there was the airfield beneath them, not surprisingly blocked with many oil drums and logs to ensure that a Japanese plane carrying troops couldn’t simply land any time it liked and take the place by storm. The pilot went low a few times to waggle his wings and show the blokes on the ground that he was of the realm, but even then it seemed a long time before ant-like figures below stole out of the jungle to remove the obstacles and clear the runway. Even then, it wasn’t easy. As the plane descended it was buffeted by the hot winds coming up from the valley and many of the soldiers lost their breakfast into their tin hats.

Colonel Owen was waiting for them as they alighted, and just as he had done two days earlier, within minutes of landing they were heading down the track to Oivi, four hours march away.

Back down the track, Doc Vernon had just finished trying to reorganise the medical staging post there and was resuming his journey northwards in the company of Sergeant Jarrett of ANGAU when a young police boy overtook them and handed Sergeant Jarrett a note. Without a word Jarrett read it and passed it over to Doc. There was news. The Japs had landed at Gona and were already moving inland towards Kokoda.

Doc, the senior man, took over. ‘I’ll go on. There’s no medical officer with those 39th youngsters and they will likely be needing one. You go back to Efogi and get them ready for casualties.’

With which they parted.

Two days march behind the good doctor, Captain Dean’s C Company of the 39th struggled their own way forward, doing it every bit as tough as Sam Templeton’s B Company had found it two weeks earlier. If there was inspiration for the men in the middle of all the agony, it was Father Nobby Earl who, though not physically fit and clearly suffering with every step, never breathed a word of complaint. Not a single one. Men didn’t like to whinge when Father Nobby could do what he had done.

Five hours after the first half of the platoon had disembarked at Kokoda, in the mid-afternoon the DC3 returned, bringing the second half of the platoon, under the command of Sergeant Ted ‘Pinhead’ Morrison. These men had been so rushed into action that on the plane they unloaded the newly issued Bren guns, fresh from the boxes packed by their manufacturers at the arms factory in Lithgow. Again, Colonel Owen was the first man they saw at the foot of the plane stairs, looking relieved to see them. As it happened the colonel knew Sergeant Morrison quite well from having served with him in a militia battalion before the war, and he hailed him with warmth…

‘What the Devil are you doing here, Pinhead?’

‘Getting ready to fight for you, Sir. What’s the plan?’

‘You’ll have to get straight on down to Oivi and join Lieutenant McClean there.’

‘Oivi… Where’s that?’

114

In response, Colonel Owen pointed in a roughly northerly direction to the end of the airfield where the beginning of a small track was just visible, disappearing into the thick kunai grass. He said: ‘Just keep going down that track and you’ll get there… ’

So off they went. At this point, the newly arrived Australians took the total number of Maroubra Force to 480 men, most of whom had never fired a shot in anger. Ranged against them somewhere between Kokoda and Buna were some fifteen hundred crack Japanese troops, with ten thousand more soon to reinforce them.

By the time Lieutenant McClean had arrived with his men at Oivi, late on the afternoon of 26 July, there was barely time to settle before the Japanese attacked. There would be no ambush this time and, just after three o’clock, the Australians suddenly came under extraordinarily heavy fire from their front and right. In a bizarre strategy, the Japanese interrupted their assault of massive firepower with attempts to coax the Australians from their cover by calling out such things as—and this one particularly would stay in Joe Dawson’s memory—‘Come forward, Corporal White!’

115

(Did they

really

believe that among these several hundred Australian soldiers there would be a corporal named White who would then stand up and walk forward when he heard his name… only to be cut down by their guns?)

As ever, it wasn’t easy to see the Japanese soldiers, but their bullets and mortars and heavy shells were all too apparent. With mortars and shells, particularly, the Japanese were much better equipped for this fight than the Australians. Not only had all of the Japanese equipment been designed for use in jungle and mountain conditions, but in addition to their individual heavy machine guns and mortars, the Japanese troops were supported by mountain artillery units. The light mountain guns could be dismantled for movement along narrow mountain tracks, and quickly reassembled when required for combat. These mountain guns, mortars and heavy machine guns would give the Japanese a deadly edge over the relatively lightly armed Australians.