Kokoda (58 page)

In the mid-afternoon of 10 September, the order came through. Brigadier Potts was to return to Moresby immediately, for ‘consultation’, with General Rowell and General Allen, with his position in overall command of the Australian forces defending Port Moresby taken by Brigadier Selwyn Porter. Potts’s departure was bitterly resented by his senior staff and the soldiers under his command— most of whom understood how well he had led them and that many of them owed their lives to him. Stan Bisset, for one, was appalled at the treatment of Potts. Yes, it was ostensibly for consultation, but to remove a battlefield commander when the battle was still effectively in progress was an obvious humiliation and it was deeply resented.

Another change was that the decimated ranks of the 2/14th and 2/16th were formed into one composite battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Albert Caro, and obliged to struggle on from there, continuing to carefully leapfrog each other back down the track.

Immediately after Ralph Honner had returned to Koitaki with the remnants of the 39th, he was called to Port Moresby and told by General Rowell that he had to ‘front the bull’. In army terminology this meant he would have to report to his commanding officer, which in this case was General Blamey, who had himself just arrived for his first look at the situation in Moresby. This was not because General Blamey had specifically requested that Honner come to see him, but because Major General Sydney Rowell was sure that General Blamey would want to consult closely with someone like Ralph Honner who had so recently returned from the battle.

Honner spruced himself up as best he could—polished his shoes and tried to put something that looked like a crease in his trousers— and duly reported to Blamey in the New Guinea Force HQ.

‘Good morning, Honner,’ the General greeted him pleasantly, if a little vacantly, clearly having no idea who Honner was. ‘You’ve just arrived in Moresby from Australia have you?’

‘No, Sir,’ Honner replied, staggered at the level of his commanding officer’s ignorance, ‘I have been in Papua now for some time.’

238

(Could Blamey be serious? How could the general not even know who had been in charge of the 39th Battalion for the last four weeks, fighting on the frontline against the Japanese? How could he not know something as basic as that, and yet still have been sending orders from three thousand miles away about how the Japanese should be routed? It simply beggared belief.)

The conversation proceeded for the next half hour or so, covering a variety of general matters, not one of which included the actual campaign then underway. Here was the highest officer of the Australian Army, on his one visit to New Guinea, in the presence of one of his leading officers in the field, and yet he posed not a single question. To Honner it seemed as if Blamey had no interest in how the Maroubra Force campaign had fared, what ideas Honner might have for improving Australian performance, or even what weaknesses he might have determined in the Japanese fighting approach. Nothing! After a time, Honner left, shaking his head in wonder as soon as it was safe to do so.

Long had he laboured, great was his suffering, but the time of redemption was near. Now back in Sydney, after hitching a ride on a plane out of Moresby, Damien Parer was showing his bosses the film he had salvaged from his trek, and already sketching out a rough script. Damien was a little disappointed with what he had managed to shoot, but this was perhaps only because he knew just how graphic other scenes were. For his bosses, however, the footage was a revelation. They had simply had

no idea

that conditions were so appalling for the soldiers, and immediately they knew they had a very good documentary on their hands. What’s more, they knew who they wanted to front it… Damien. He had been up there, he had shot the film, he presented well, he was perfect. Damien resisted, protesting that he was the man behind the camera, and that it wasn’t right for him to step in front of it. But his bosses insisted and he reluctantly agreed.

Back at the front, by the morning of 12 September the Australian soldiers had withdrawn to the top of Ioribaiwa Ridge, where the plan was to consolidate before throwing the fresh soldiers of the 25th Brigade—who had just arrived under the command of Brigadier Ken Eather—into aggressive flanking manoeuvres against the Japs.

As was ever the way in war, however, it didn’t quite work out as planned. Lacking experience in jungle fighting, the fresh troops who moved forward on the left flank simply became lost, while those on the right flank moved smack bang into a concentration of General Horii’s few remaining crack troops and were routed. Even worse, the bulk of the exhausted soldiers dug in at the top of the mountain were easy targets for General Horii’s mountain guns which had once again come forward.

It was that rarest and most precious of all things in this war—a real press conference where the likes of Thomas Blamey could be made to answer for what Chester Wilmot, for one, saw as the sheer insanity of some of his actions and orders.

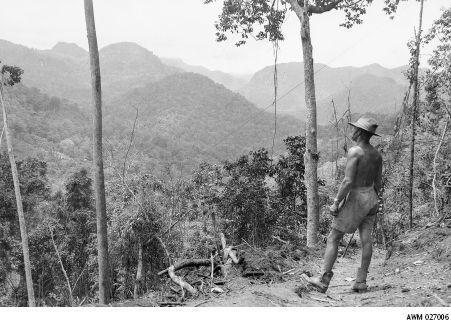

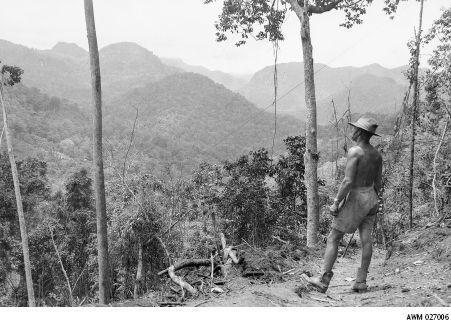

Blamey began, being quite upbeat. ‘The Japs are already feeling the difficulties of supply,’ he said. ‘They have a few light mountain guns, but they have no chance of getting heavy supplies along that terrible track with its precipices and jagged ridges and awful river crossings and great stretches of track that are merely moving streams of black mud. Moresby is in no danger, and I think we shall find that the Japs will be beaten by their own advance, with its attendant problems of supply. It will be a Japanese advance to disaster, an Australian retreat to victory.’

239

All well and good. But after some preliminary questions by other journalists, the fearless Wilmot got right to the point: ‘General Blamey, do you think that green uniforms are necessary for our soldiers in the jungles of New Guinea?’

General Blamey, with a clear flash of anger at the near-impertinence of the very question replied: ‘Not at all. It is true that those uniforms were designed specifically for the jungles of India, but I have never seen any evidence that the jungle of New Guinea is any different from the jungle of India. I think the uniforms the soldiers are wearing are quite adequate… ’

Wilmot continued: ‘Well, I can provide several thousand witnesses who have actually fought in New Guinea who can provide evidence to the contrary… ’

240

If it wasn’t quite a declaration of war from one man to another, it was as close to it as a press conference could allow and, from that moment, both Wilmot and Blamey knew that the other was gunning for him with every means available. Wilmot was outraged by what he had seen in New Guinea and held Blamey personally responsible for a lot of it; Blamey was apoplectic at Wilmot’s presumption in not only blaming him, but then endeavouring to broadcast it. For the moment, each took the view that the other would keep…

How long could the Australians stay on the forward slopes of Ioribaiwa, simply being picked off by mountain guns sending whistling shells right among them? It was absurd, most particularly when their own firepower was now just a few hours march to their rear. The obvious thing to do was to withdraw to the far more defensible Imita Ridge—just four hours march north of Ower’s Corner—and bring the Japs to within range of the Australian guns, and to make their ‘line in the sand’ there. That far, and no further.

So it was, that on the morning of 16 September, Brigadier Eather got a message through to Tubby Allen: ‘Enemy feeling whole front and flanks. Do not consider can hold him here. Request permission to withdraw to Imita Ridge if necessary.’

Despite Allen’s previous admonition that the 25th Brigade had to draw a line in the sand on Ioribaiwa and never fall back from it, he reluctantly agreed to the request—at least noting that it would bring the Australian soldiers that much closer to the supply lines and stretch the Japs that much further. As well, it would give the brutes a little curry with their rice, once they indeed got within range of the Australian guns.

On his return to Australia, after just three days in Moresby and nowhere near the frontline, Blamey publicly expressed the view that the situation in New Guinea was well in hand, and also evinced confidence in the performance of Lieutenant General Rowell, Major General Tubby Allen and their troops. Yes, the Japanese were now uncomfortably close to Moresby, but on the other hand their exhausted troops were at the end of an extremely long supply line, while the Australians were now well provisioned and daily receiving fresh reinforcements. It was likely that the Japanese would get little further.

This was not a view shared by MacArthur, or at the very least it was not one he expressed. For despite the Australian heroism to this point—fighting successfully against extraordinary odds and managing to weaken the Japanese with every day they kept them out there—back in Brisbane all that GHQ focused on was the markers on the map, which showed the invaders getting closer and closer to Port Moresby. This feeling was compounded after one of the key members of MacArthur’s clique, General Kenney, had made his own second trip to New Guinea and returned to tell MacArthur that the fall of Moresby was imminent. Though Kenney did not get remotely close to the actual fighting, he was firm in his view, his words echoing what General Sutherland had expressed to him on his first afternoon in Brisbane, that the Australians simply weren’t up to it.

‘You’ve got to get some Americans up there,’ Kenney now told MacArthur. ‘They don’t know anything about jungle fighting, but the Australians don’t know that, and the Americans don’t know it either. So we’ll go up there all full of vinegar and the Australians will be afraid that the Americans will take the play away from them. So both will start fighting, and we’ll get the damned Japs out of there… ’

The scheme would have a bonus benefit, he told MacArthur.

‘We’ve got to stop stories that the Yanks are taking it easy in Australia and letting the Aussies do all the fighting.’

241

What was clear was that while they were waiting to throw the Americans into the fray, something had to be done, that the situation had to be taken in hand by someone who could turn it around. (And perhaps, a cynic might say, be on site with the failed soldiers of his own nation, to take the lion’s share of the blame should Moresby fall.) Blamey was at least part of the answer.

With that in mind, MacArthur called the Australian Prime Minister John Curtin, and they had a strained conversation on the evening of 16 September 1942.

‘The retrogressive nature of the tactics of the Australian ground forces defending Port Moresby seriously threatens outlying airfields,’ MacArthur told Curtin. ‘If they can’t stop the Japs, the Allies in New Guinea will be forced into such a defensive concentration as would duplicate the conditions of Malaya.’

242

In sum: the decimation of both Australian interests and Australian soldiers. The only way around it, MacArthur maintained, was to get American troops involved, which he, MacArthur, would take care of; while General Blamey would have to return to New Guinea full time and give his soldiers the ginger they needed to get cracking. It would be for Blamey to ‘energise the situation’.

When MacArthur expressed the same view to Blamey, and insisted that he return to New Guinea, the Commander of the Australian Forces showed no enthusiasm whatsoever, still without quite saying ‘no’. It was only when John Curtin, at MacArthur’s specific behest,

insisted

that Blamey return that he agreed he would.

(In all of these discussions, the possibility that the military

leadership

wasn’t up to it—as shown by putting inadequate and ill-supplied forces up against an enemy overwhelming in its numbers and firepower—was never broached. As the markers on MacArthur’s map retreated, there were only two possibilities: that the Australian soldiers were lacking; or the leadership which had put them there in insufficient numbers with inadequate firepower was lacking, and MacArthur was all in favour of the former view.)