Kokoda (70 page)

Joe Dawson and his beloved Elaine married a few months after his return from Kokoda and are still going strong. Joe is now eighty-two, and in May 2003 he and Elaine celebrated their sixtieth wedding anniversary in the beautiful seaside town of Forster, just north of Newcastle. (It was a far happier day than the one just a few months after their actual wedding, when Joe informed the newly pregnant Elaine that, despite everything, he was going

back

to New Guinea to fight some more. He did so, but mercifully returned safe and sound at war’s end.)

Smoky Howson went back to the market gardens before marrying, becoming a builder and raising children, but was always marked by his experience in the war. Haunted by events such as his killing of the Japanese soldier who was staring up at him, he spent a good deal of time over the years in institutions devoted to mental health. Though he had just about never cried during the war, sometimes after it, he just couldn’t stop. Many was the night he’d wake in a cold sweat, looking intently into the eyes of the Japanese soldier, who was

still

looking straight back at him, and sometimes he’d wake to the sound of his wife screaming, only to realise that he was choking her. Other times he’d relive his grisliest work of all during the war, sawing the tops off dead blokes’ heads, and ripping their chest cavities open with a sharp knife, with the blood and muck getting all over him. This was all so that they could send the brains and hearts of dead soldiers to the University of Melbourne for testing and God knows what. Some damn thing anyway. He hated working in Moresby’s military morgue—with all those bloody great big foot-long rats running around everywhere—but that was what they asked him to do after he’d refused to join the AIF, and that’s what he did. It was just that it was so damned hard to forget it. The world was back at peace, but he wasn’t. He would never be. At least the grog helped, a little… Smoky Howson lived until June 2003.

After the war, Ralph Honner soon returned to civilian life, and continued what he’d started before the war, which was raising a family of four with his beloved wife Marjorie. A sign of just how long he’d been away, though, came a few days after he got home, when his two small sons reported to the nuns at their school that a strange man had come into the house and was cuddling their mother all the time, even in her bedroom!

Back in the swing of civilian life, Ralph moved to Sydney with his family and became very active in the Liberal Party and the United Nations Association among other things. Professionally, he became the long-time Chairman of the War Pensions Assessment Appeal Tribunal, and also had a stint with the Diplomatic Corps as he became Australia’s Ambassador to Ireland from 1968 to 1972, after which he retired.

Ralph Honner died at eighty-nine, on the morning of 14 May 1994, not long after doing what he did every morning—raising the Australian flag on a specially constructed flagpole in his garden. His funeral at St Mary’s Catholic Church in Miller Street, North Sydney, was standing room only. And one was there, an old Japanese gentleman, who had, unannounced, arrived the day before from Shikoku. He walked up to the coffin and bowed low and long, before handing a letter to Ralph’s sons, noting the enormous respect he and his fellow old Japanese soldiers had for Colonel Ralph Honner, the warrior.

In some ways Alan Avery never recovered from the death of his best friend, Bruce Kingsbury, who had died so valiantly in the defence of Isurava. Every day he thought of Bruce, every day he missed him, every day something felt empty inside. Alcohol helped fill the hollow a little, but never for long enough. After the war he worked in a nursery and married, but the marriage broke up in 1965. The one place he seemed to find calm, oddly enough, was up in the same area of Queensland where the 2/14th had done so much of its preparation before heading off to New Guinea. It was more or less the last place he’d felt pretty good, so maybe it was natural enough. Alas, after a bout of prolonged ill-health, Alan finally gave up on living, and at the age of seventy-seven in May 1995, shot himself dead.

For his courageous efforts at Gona, Stan Bisset was awarded the Military Cross. After the war, he returned to Melbourne to marry, and he and his wife Shirley raised four children, as he worked with great success in the administrative side of a business that built gas and combustion furnaces. In 1970, when his marriage ended, he moved to Gladstone in Queensland, where he met the woman who was to become his second wife, Gloria. He now lives in quiet retirement in Noosa with Gloria, not far from where he and the rest of the 21st Brigade were training in preparation for their embarkation for New Guinea. It is Stan who organises the annual reunion of the 2/14th Battalion, and helps keep everyone in touch.

When I asked him in July 2003 what the greatest satisfaction of his life had been, he said that apart from seeing his children grow, it had been to help ensure that a memorial was built for his fallen comrades and brother up on Mount Ninderry, near Yandina, as well as feeling like he had some part in the wonderful memorial at Isurava being built through his own lobbying.

Speaking of which…

The village of Isurava, as it was, is no more. In 1988 the villagers decided to change sites and upped sticks to move about an hour and a half’s walk closer to Kokoda, not too far from the place where Colonel Honner had placed his first standing patrol forward of Isurava to give fair warning when the Japanese soldiers were on their way. It was a place that had closer access to water and more flat arable land for their gardens—a place, too, where killing on a massive scale had not taken place.

In 1992, Paul Keating was the first Australian Prime Minister to visit Kokoda itself. On the helicopter ride from Moresby he discussed the significance of the Kokoda campaign with Professor David Horner of the Australian National University, one of the foremost experts in the field. Flying over the track on which so much blood had been spilled, looking down upon the gorges and cruel spurs that his fellow Australians had fought across fifty years before, clearly affected the prime minister. Upon emerging from the helicopter, which landed just near a modest memorial in honour of what the Diggers had accomplished in these parts, he immediately fell to his knees and kissed the ground. It was a symbol of the fact that Australia was finally recognising what had been achieved in this place. Here, Mr Keating said, the Australian soldiers were

not

fighting for Empire, they were fighting ‘not in defence of the Old World, but the New World. Their world. They fought for their own values.’ Which was in turn why, he explained, ‘for Australians, the battles in Papua New Guinea were the most important ever fought.’

317

Amen to that.

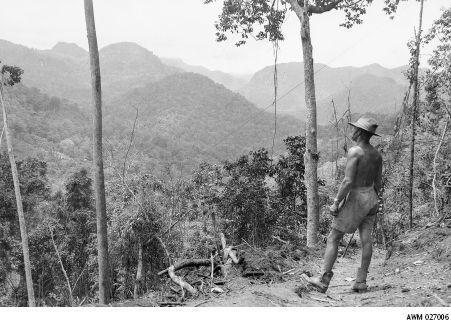

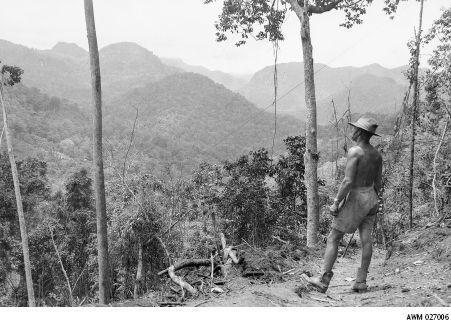

And the New Guinea jungle? The butterflies that fluttered around despite the battle—on the reckoning that their own world would soon win, whatever happened here—were right, and the jungle continues to exert its primeval timeless force, returning all that is, to what it once was. The deep weapons pits, once big enough to hold two men with machine guns, are now only shallow depressions on the jungle floor as year by year the ground has crumbled and the thick undergrowth grown back. The rough huts that were built as the staging posts have now rotted and disappeared. The skeletons of Japanese and Australian soldiers have both, for the most part, simply enriched the soil, while old bullets and shell casings continue to corrode into nothingness, their anger entirely spent.

Not so long from now there will be little left physically in the highlands to show that a great battle was once fought there. Spiritually though, the legacy of the 39th Battalion, the 2/14th, the 2/16th, the 2/27th and all the rest, will endure. At the very least, in their native Australia, the understanding of what they achieved, and the sacrifice they made has never been stronger, and it will get stronger still.

There remain, too, a handy group of survivors who treasure the memory of the fallen and will continue to do so to their own dying days. It was well put by one Private Burton, a veteran of the Kokoda campaign from first to last, who wrote in his diary: ‘Now on Kokoda Day, when the names are read out of those killed in action, I know them all and still see them as they were. They will never become old or embittered. Just laughing kids forever.’

318

They shall grow not old, as we that are left grow old. Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we shall remember them.

We shall remember them.

It was late on a shining Sunday afternoon in early August, 2009. They were old men, all nudging 90 and beyond, gathered in a circle under the beautiful dome of Melbourne’s Shrine of Remembrance. The filtered afternoon light bathed their faces in an ethereal glow as they bowed their heads and the old Lieutenant of ‘B’ Company, ‘Kanga’ Moore, uttered those precious, poignant words: ‘Age shall not weary them, nor the years condemn. At the going down of the sun, and in the morning, we shall remember them.’

‘We shall remember them,’ the old men rasped in unison. ‘Lest we forget.’

All over Melbourne and in parts north on that same afternoon, nine much younger people were mostly with their families, engaging in last minute preparations, getting ready for a long journey ahead, first by plane and then by foot. The unifying focus of both the old ones and the young ones was, of course, events on the Kokoda Track in 1942. The old men were the surviving veterans of the 39th Battalion who had so courageously fought there in 1942, and formed such bonds that they have regularly seen each other since. The younger people were trekkers, wanting to honour what those older men and their fellow Diggers had accomplished in thwarting the Japanese invasion, by walking the Track…

Alas, at 9.56 am on the following Tuesday morning, the twin Otter plane bearing them to Kokoda from Port Moresby crashed into a cliff, just north of the iconic battle site of Isurava, where the 39th Battalion had made their heroic stand against the Japanese in the last days of August, 1942.

In an unfathomable tragedy, all of the trekkers were killed, and for days the news dominated the front pages of the papers and led the news bulletins. So many young Australians losing their lives was always going to produce great national emotion. But this accident, occurring in a place as significant as the Kokoda Track, a place made iconic by Australian soldiers – a fair number of whom were still alive – saw an outpouring of extraordinary national grief, far beyond what might have been expected had the same tragedy occurred in a non-descript jungle in another land.

Certainly, there was some muted questioning of what possessed the trekkers to be there in the first place, what made them go to an inherently dangerous country, to get into a small plane flying over such mercilessly rugged and unforgiving ground, all in the hope of putting themselves through nine days of an agonising walk… but most Australians understood.

The trekkers were wanting to pay homage to, if not a new Australian legend, then at least a relatively newly

acknowledged

Australian legend. Twenty years ago, for most Australians younger than sixty, ‘Kokoda’ was little more than a recognisable name for some battle or other that occurred somewhere up New Guinea way, probably during World War II. But as to detail, as to feeling a great passion for what occurred, the broad mass of the country knew little and cared less. It is only in the last twenty years that the story of ‘Kokoda’ has resonated with broad swathes of the country.

And yet, how could that be? Gallipoli was legendary almost from the moment news of it got out, and has barely wavered since. So why was Kokoda so different? How could a battle fought in 1942 have been largely ignored for half a century, only to roar back into favour to take its rightful place as pre-eminent in all Australian battles? For decades, Kokoda was a legend denied. The first denial, of course, came at Koitaki on 9 November 1942 when, instead of lauding the veteran Australian troops of the mighty 21st Brigade for their heroism and stunning achievement in thwarting the Japanese thrust, General Blamey had the hide and the colossal lack of judgement to lecture them on cowardice, and utter those infamous words: ‘Always remember that the rabbit that runs is the rabbit that gets shot.’