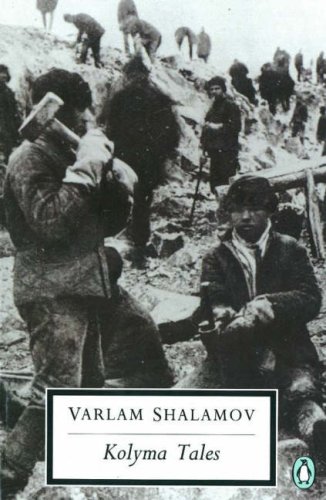

Kolyma Tales

Authors: Varlan Shalanov

PENGUIN TWENTIETH-CENTURY CLASSICS

KOLYMA TALES

Varlam Tikhonovich Shalamov was born in 1907. A prose writer and poet, he has become known chiefly for his

Kolyma Tales

, in which he describes life in the Soviet forced-labour camps in north eastern Siberia. It is a theme he returns to in a second collection of stories,

Graphite

.

Shalamov was arrested for some unknown ‘crime’ in 1929 when he was only twenty-two and a student at the law school of Moscow University. He was sentenced to three years in Solovki, a former monastery that had been confiscated from the Church and converted into a concentration camp. In 1937 he was arrested again and sentenced to five years in Kolyma. In 1942 his sentence was extended ‘till the end of the war’; in 1943 he received an additional ten-year sentence for having praised the effectiveness of the German army and having described Ivan Bunin, the Nobel laureate, as a ‘classic Russian writer’. He appears to have spent a total of seventeen years in Kolyma.

Shalamov did manage to smuggle

Kolyma Tales

out to the West, and they were published in German and French (and only much later in English). The Soviet authorities then forced him to sign a statement, published in

Literaturnaya gazeta

in 1972, in which he stated that the topic of

Kolyma Tales

was no longer relevant after the Twentieth Party Congress, ‘that he had never sent out any manuscripts, and that he was a loyal Soviet citizen’. Once Shalamov had renounced

Kolyma Tales

, he was permitted to publish his poems in the Soviet Union, and these began to appear in literary journals in 1956. Four small collections were published between 1961 and 1972. When he first came across an anthology of Shalamov’s poetry, Solzhenitsyn said that he ‘trembled as if he were meeting a brother’. Varlam Shalamov died in 1982.

John Glad is an associate professor in the department of Slavic Studies at the University of Maryland. His translation of

Kolyma Tales

was nominated for the American Book Award.

VARLAM SHALAMOV

Translated from the Russian by

JOHN

GLAD

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

The following stories in this collection were first published in 1980 in the USA by W. W. Norton & Company, ©John Glad 1980, under the title

Kolyma Tales. On Tick, In the Night, Dry Rations, A Child’s Drawings, Condensed Milk, The Snake Charmer, Shock Therapy, The Lawyers’ Plot, Magic, A Piece of Meat, Major Pugachov’s Last Battle, The Used-Book Dealer, Lend-Lease, Sententious, The Train and Quiet.

Other stories in this collection, as follows, were first published in 1981 in the USA by W. W. Norton & Company, © John Glad 1981, under the title

Graphite. Through the Snow, An Individual Assignment, The Apostle Paul, Berries, Tamara the Bitch, Cherry Brandy, The Golden Taiga, A Day Off, Dominoes, Typhoid Quarantine, The Procurator of Judea, The Lepers, Descendant of a Decembrist, Committees for the Poor, The Seizure, An Epitaph, Handwriting, Captain Tolly’s Love, The Green Procurator, The Red Cross, Women in the Criminal World, Grisbka Logun’s Thermometer, The Life of Engineer Kipreev, Mr Popp’s Visit, The Letter, Fire and Water and Graphite.

This collection published in Penguin Books 1994

Original stories copyright © Iraida Pavlovna Sirotinskaya, 1980

Translation copyright © John Glad, 1980, 1981, 1994

All rights reserved

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

ISBN: 978-0-14-196195-8

Foreword

In our positivistic civilization, one of the inappropriate compliments sometimes paid to literature is to reduce it to ‘artistic knowledge’. Not that such cognizance does not exist, but art is both more and less than knowledge. It is unique,

sui generis

, a thing in and of itself. And its experience is one of the precious justifications for our own existence.

While the work of art ‘enriches’ (another unsuitable analogy), at the same time it creates a postpartum sense of loss: the first experience is unique, an act never to be repeated – no matter how great the understanding and appreciation later achieved through the most intent study. If only we could erase from our minds the memory of our favorite books and return to the still unsuspected wonder contained in those works! When we recommend them to our friends, we do so in envy – that we cannot recreate that initial magic for ourselves. And the more we love a book, the greater is our own wistfulness. We cannot step into the same river twice, not so much because the river is different, but because we ourselves are in flux.

If you are about to read the stories of Varlam Shalamov for the first time, you are a person to be envied, a person whose life is about to be changed, a person who will envy others once you yourself have forded these waters.

Kolyma Tales

tell of life in the Soviet forced-labor camps and the stories are regarded by historians as important documentary materials. Nevertheless, the

Gulag

has many chroniclers, but only one Varlam Shalamov. This book can be profitably read as fictionalized history; the phrase ‘historical novel’ is itself a ‘historical accident’; history in literature is not limited to the larger genres. But

Kolyma Tales

is much more than that. If the camps had never existed, this volume, one of the great books of world literature, would be only the more astounding as a creation of the imagination.

Separated from Alaska by the 55-mile wide Bering Strait, Kolyma was first used as a place of exile and a source of gold under the Czars. In 1853, for example, the Czarist official Muraviov-Amurski was able to send to St Petersburg three tons of gold mined by convict labor. Over half a century later the Soviet Union, the world’s second largest gold producer, also exploited Kolyma as an enormous prison, where the principal occupation was gold-mining.

It is extraordinarily difficult to come up with a reliable estimate of the total number of political victims during the Soviet period. On 6 April 1990 the Soviet general and historian Dmitry Volkogonov, during a lecture delivered at the Pentagon, gave a preliminary estimate of the total number of ‘repressed persons’ (those imprisoned and/or murdered): 22.5 million. The estimates of some non-Soviet historians run considerably higher. If we speak only of Kolyma, there is a 1949 estimate by the Polish historian Kazimierz Zamorski of 3 million people exiled there, not more than 500,000 of whom supposedly survived.

1

In 1978 Robert Conquest estimated that 3 million people met their deaths in Kolyma – certainly not fewer than 2 million.

2

It is hard to grasp such figures.

The years 1937–9 were the period of the Great Purges. Millions of people were arrested, held for months in appalling prison conditions, tried on trumped-up charges and either executed or shipped to Siberia. Emaciated as a result of a hopelessly inadequate diet, denied even sufficient drinking water and toilet facilities, freezing from the cold, they would arrive at the Siberian ports of Vladivostok, Vanino or Nakhodka after a rail trip that lasted between thirty and forty days. There they were held in transit camps for varying periods of time.