Kosher and Traditional Jewish Cooking: Authentic Recipes From a Classic Culinary Heritage: 130 Delicious Dishes Shown in 220 Stunning Photographs (36 page)

Authors: Marlena Spieler

This halek is fragrant with rose water, cinnamon and nutmeg as well as the sweet flavours of dried fruits and nuts, which are so beloved by Persian Jews. Keep chilled in the refrigerator until you are ready to serve it.

SERVES ABOUT 10

60ml/4 tbsp blanched almonds

60ml/4 tbsp unsalted pistachio nuts

60ml/4 tbsp walnuts

15ml/1 tbsp skinned hazelnuts

30ml/2 tbsp unsalted shelled pumpkin seeds

90ml/6 tbsp raisins, chopped

90ml/6 tbsp pitted prunes, diced

90ml/6 tbsp dried apricots, diced

60ml/4 tbsp dried cherries

sugar or honey, to taste

juice of

1

/

2

lemon

30ml/2 tbsp rose water

seeds from 4–5 cardamon pods

pinch of ground cloves

pinch of freshly grated nutmeg

1.5ml/

1

/

4

tsp ground cinnamon

fruit juice of choice, if necessary

1

Roughly chop the almonds, pistachio nuts, walnuts, hazelnuts and pumpkin seeds and put in a large bowl.

2

Add the chopped raisins, prunes, apricots and cherries to the nuts and seeds and toss to combine. Stir in sugar or honey to taste and mix well until thoroughly combined.

3

Add the lemon juice, rose water, cardamom seeds, cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon to the fruit and nut mixture and mix until thoroughly combined.

4

If the halek is too thick, add a little fruit juice to thin the mixture. Pour into a serving bowl, cover and chill until ready to serve.

Nutritional information per portion: Energy 207kcal/863kJ; Protein 5.1g; Carbohydrate 14.9g, of which sugars 14.5g; Fat 14.6g, of which saturates 1.4g; Cholesterol 0mg; Calcium 66mg; Fibre 2.8g; Sodium 42mg.

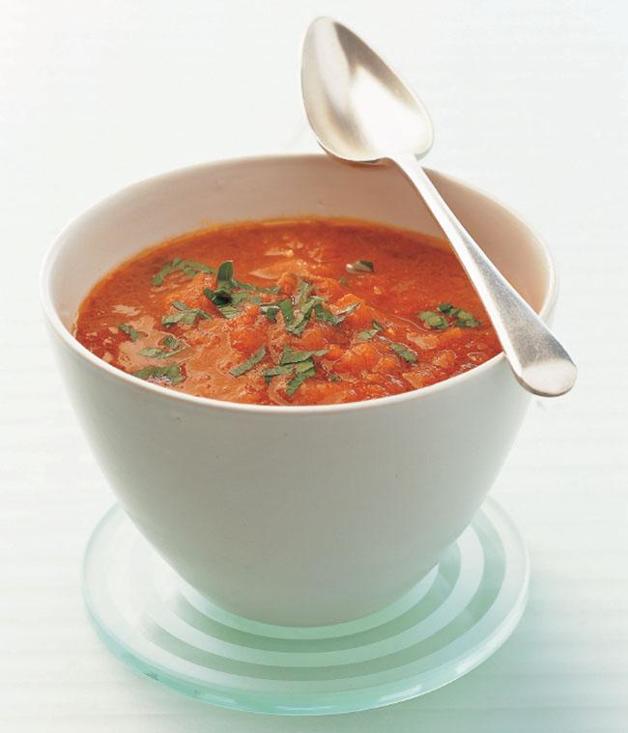

This is the Yemenite chilli sauce that has become Israel’s national seasoning. It is hot with chillies, pungent with garlic, and fragrant with exotic cardamom. Eat it with rice, couscous, soup, chicken or other meats. It can be stored in the refrigerator for up to 2 weeks.

MAKES ABOUT 475ML/16FL OZ/2 CUPS

5–8 garlic cloves, chopped

2–3 medium-hot chillies, such as jalapeño

5 fresh or canned tomatoes, diced

1 small bunch coriander (cilantro), roughly chopped

1 small bunch parsley, chopped

30ml/2 tbsp extra virgin olive oil

10ml/2 tsp ground cumin

2.5ml/

1

/

2

tsp turmeric

2.5ml/

1

/

2

tsp curry powder

seeds from 3–5 cardamom pods

juice of

1

/

2

lemon

pinch of sugar, if necessary

salt

1

Put the garlic, chillies, tomatoes, coriander, parsley, olive oil, cumin, turmeric, curry powder, cardamom seeds and lemon juice into a food processor or blender. Process until well combined, then season with the sugar and salt.

2

Pour the sauce into a serving bowl, cover and chill in the refrigerator until ready to serve.

Nutritional information per portion: Energy 326kcal/1361kJ; Protein 7.1g; Carbohydrate 21.4g, of which sugars 17.5g; Fat 24.3g, of which saturates 3.7g; Cholesterol 0mg; Calcium 142mg; Fibre 8.6g; Sodium 63mg

The foods of the Jewish table are global by nature, reflecting the flavours of the countries where Jews have settled. They also have their roots in tradition. Ashkenazi and Sephardi foods are very different but cross-cultural marriages and the intermingling of different people have blurred the boundaries.

Exile has been a common thread throughout Jewish history. It is this, linked with intrinsic religious and cultural considerations, that has been a major factor in developing a cuisine that is so diverse. As communities fled from one country to another, they took with them their culinary traditions but also adopted new ones along the way.

With the destruction by the Romans of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70

CE

(

AD

), the Jews were banished from their holy city. Since that date, they have travelled the world, establishing communities before being forced to flee once more.

Jews spread to nearly every corner of the globe and this dispersal or diaspora has helped to create the cultural and liturgical differences that exist within a single people. Following the dispersal, two important Jewish communities were established, which still define the two main Jewish groups that exist today: the Sephardim and the Ashkenazim, who each have their own individual culture, cuisine and liturgy.

The first of these communities was in Iberia and was called Sepharad after a city in Asia Minor mentioned in Obadiah 20. The second was in the Rhine River Valley and was called Ashkenaz, after a kingdom on the upper Euphrates.

A painting by Francesco Hayez of 1867 of the destruction of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem by the Romans in 70

CE

(

AD

).

Jews who settled in Iberia spoke Ladino, a dialect of Castilian Spanish written in Hebrew script. In many respects, their lifestyle was not so very different from that of their Arab neighbours, who had a similar outlook of generous hospitality.

The food the Sephardi Jews ate, and the way they cooked it, was a blend of their own heritage and dietary laws, with distinct influences from the Iberian and Arabic culinary tradition. What emerged was a cuisine rich with the flavours of the region.

At its heart, Sephardi cooking still has the warm undertones of Spain: it is olive oil-based, rich with fish from the sea and the vegetables of a warm climate, fragrant with garlic, herbs and spices. When meat is used, it is usually lamb.

The Sephardim also introduced their own influences on the Iberian and Arab cuisines. Even today, if you enquire in Andalucía in Spain as to what have been the major influences on their cuisine, the Jewish contribution will be acknowledged alongside that of the Moors.

Sephardi cooking reflected Sephardi life: sensual and imbued with life’s pleasures. This attitude went a lot further than just the food. It is reflected in all the celebrations for life’s happy occasions too. For instance, in Sephardi tradition, a typical wedding celebration lasted for two weeks, and a Brit Milah or Bar Mitzvah celebration lasted for a week. These old traditions still live on today.

The Sephardim, who had flourished in Spain for centuries, then found the tide beginning to turn against them. Shortly before the end of the 14th century, antagonism erupted into violent riots and thousands of Jews were massacred.

Many of those who survived were forced, on pain of death, to convert. These Jews were known as

conversos

or – less politely –

marranos

, which means pork eaters. They and their families often continued their religious practices in secret. Traditional food, and the rituals associated with it, became a source of comfort for the

conversos

and a reminder of their history.

For a few decades these clandestine Jews flourished but they were a thorn in the flesh of the Spanish rulers and led to the Spanish Inquisition at the end of the 15th century. In 1492 all the remaining Jews in Spain were expelled. They scattered to North Africa, Europe, the Middle East and the New World. With each migration, Sephardi Jews encountered new flavours, which they introduced into their own cooking.

The Jews who fled to the Rhine Valley were, over the centuries, to spread across Europe. Ashkenazi Jewish communities of France, Italy and Germany, which were so numerous in the early Middle Ages, were pushed further and further eastwards due to persecutions from the time of the Crusades, which began early in the 11th century. Many Jews fled to Eastern Europe, especially Poland. They spoke Yiddish, which is a combination of Middle High German and Hebrew, written in Hebrew script. Their non-Jewish neighbours ate abundant shellfish and pork, cooked with lard, and mixed milk with meat freely, none of which was permitted for Jews, so the only answer for them was to keep themselves apart. In Czarist Russia, they were only allowed to live in the Pale of Settlement, a portion of land that stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea. The Ashkenazi Jews lived – often uneasily – in

shtetlach

(villages) and never knew when they would be forced to flee again.