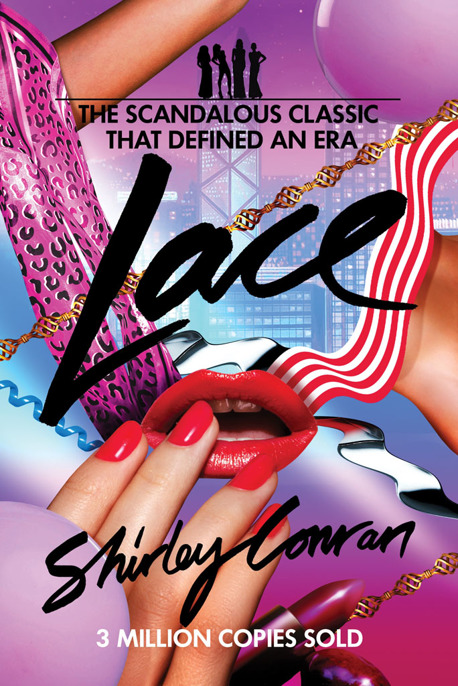

Lace

Authors: Shirley Conran

Also by Shirley Conran

FICTION

Lace 2

Savages

Crimson

Tiger Eyes

The Revenge

CHILDREN’S FICTION

The Amazing Umbrella Shop

NON-FICTION

Superwoman

Superwoman Yearbook

The Magic Garden

Down with Superwoman

This paperback edition published in 2012 by Canongate Books Ltd,

14 High Street, Edinburgh EH1 1TE

Copyright © Shirley Conran, 1982, 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted

First published in 1982 in the USA by Simon & Schuster

and in Great Britain by Sidgwick & Jackson

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on

request from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 85786 390 4

Export ISBN 978 0 85786 800 8

eISBN 978 0 85786 536 6

Book design by Mary Austin Speaker

This digital edition first published in 2012 by Canongate Books

This book is for

my sons,

SEBASTIAN CONRAN

and

JASPER CONRAN,

with love.

CONTENTS

PRELUDE

Paris, 1963

S

CRAPE

. . .

SCRAPE

. . .

SCRAPE

. . .

The cold, hard metal dug deep into

the child’s body. She forced her knuckles into her mouth and bit against the bone as hard as she could to fight pain with pain. She didn’t dare scream. She just mumbled, “Jesus,

Jesus, Jesus,” as she bit her hand.

Tears ran down her cheeks and onto the paper pillow. Her body was trembling and clammy with cold sweat. Outside she could hear the cheerful noise of a busy Paris street, but in this small brown

room there was no sound except the scraping and her mumbling and the occasional clink of steel against steel. She would count to ten and

then

she’d scream! Surely it couldn’t go

any higher, whatever he was pushing up inside her? It felt like a dagger, persistent, cold, merciless. She wanted to vomit, to faint, she wanted to die. She couldn’t bear it to go on and on

and on. . . .

The man was intent on what he was doing as she lay on the hard table, her knees forced high and apart by the steel surgical stirrups. It had been horrifying from the moment she entered this

place, the dark brown room with the hard, high table in the middle. A line of silvery instruments and a few odd-shaped bowls lay on another table; there was a camp bed and a cloth screen in one

corner of the room. A white-aproned woman had pointed to the screen and said, “You can take off your clothes behind that.” Naked, she had shivered behind the screen, not wanting to

leave its protection, but the woman had taken her briskly by the wrist and tugged her to the table in the centre of the room. She had been positioned on her back so that her narrow hips rested on

the edge of the table, while her legs were pulled apart by the woman and lifted into the cold surgical stirrups. The shivering child felt unbearably humiliated as she gazed into the powerful

overhead light.

There had been no anesthetic. The man wore a crumpled green surgeon’s gown. He had muttered some instruction to the woman and then he had inserted two fingers into the child’s

vaginal canal; he held the cervix with his fingers as he placed his other hand on her abdomen to feel the size and position of her uterus. Then she was swabbed with antiseptic, and he pushed in a

chill speculum shaped like a duck’s bill, which kept the walls of the vagina apart and enabled him to see the opening of her uterus. The speculum didn’t hurt, but it felt cold and

menacing inside her small body. Other instruments were also inserted and then the pain started as the cervix was opened slowly with the stainless steel dilators until it was wide enough for the

operation to start. The man picked up the curette—a metal loop on the end of a long thin handle—and the excavation began. The curette moved in and around the uterus, scraping the life

out of her; it took only two minutes, but the time seemed endless to the suffering child.

The man worked quickly; occasionally he muttered to the woman who was helping him. Hardened though he was, he carefully avoided looking at the child’s face; her little feet in the stirrups

were reproach enough as he swiftly finished the job and removed each bloodied steel instrument.

As the uterus was emptied it gradually contracted back to its original size, but the child’s body was jerked with agonizing cramps until the contractions stopped.

Now she was wailing like an animal, gasping as each new pain clawed her. The man abruptly left the room; the woman swabbed her; the cloying smell of antiseptic filled the air. “Stop making

such a noise,” hissed the woman. “You’ll feel fine in half an hour. Other girls don’t make such a fuss. You should be grateful that he was trained as a real doctor. You

haven’t been messed up inside; he knows what he’s doing, and he’s fast. You don’t know how lucky you are.” She helped the thin, thirteen-year-old girl off the table

and onto the camp bed in the corner. The child’s face was gray, and she shook uncontrollably as she lay under a blanket.

The woman gave her pills to swallow, then she sat and read a paperback romance. For half an hour there was no sound in the room except for the child’s occasional stifled sob. Then the

woman said, “You can go now.” She helped the girl to dress, gave her two large sanitary towels to put in her pants, handed her a bottle of antibiotic tablets and said, “Whatever

happens, don’t come back here. You’re not likely to hemorrhage, but if you start bleeding, call a doctor

immediately.

Now get home and stay in bed for twenty-four hours.”

For one moment the woman’s carefully controlled, impersonal toughness weakened. “

Pauvre petite!

Don’t let him touch you for at least a couple of months.” Awkwardly

she patted the child’s shoulder and led her through the passage to the heavy front door.

The child paused outside on the stone steps, wincing in the sharp sunlight. Slowly, painfully, Lili walked along the boulevard until she came to a small café where she ordered a hot

drink. She sat and sipped it, feeling the sun and the warm steam on her face as a jukebox pumped out the new Beatles hit, “She Loves You”.

PART

ONE

I

T WAS A

warm October evening in 1978 with the distant skyscrapers sparkling in the dusk as Maxine glanced through the

limousine window at the familiar New York skyline. She had chosen this route for that view. Now, in the discreet, hushed comfort of the Lincoln Continental, they stood stuck in traffic on the

Triboro Bridge. Never mind, she told herself, there was plenty of time before the meeting. And the view was worth it—like diamonds sprinkled across the sky.

Her neatly folded sable coat lay beside the maroon crocodile jewel case. The nine maroon-leather suitcases—all stamped in gold with a tiny coronet and the initials M de C—were

stacked beside the chauffeur or stowed in the trunk. Maxine travelled with very little fuss and at enormous expense, usually someone else’s. She took absolutely no notice of luggage

allowances; she would say, with a shrug of the shoulders, that she liked comfort; so one suitcase contained her pink silk sheets, her special down-filled pillow, and the baby’s shawl,

delicate as a cream lace cobweb, that she used instead of a bed jacket.

Although most of the suitcases held clothes (beautifully packed between crisp sheets of tissue paper), one case was fitted as a small maroon-leather office; another carried a large medicine box

packed with pills, creams, douches, ampoules, disposable syringes for her vitamin injections and the various suppositories that are considered normal treatment in France but frowned on by

Anglo-Saxons. Maxine had once tried to buy syringes in Detroit—

mon Dieu,

could they not tell the difference between a drug addict and a French countess? One had to look after

one’s body, it was the only one you were going to get and you had to be careful what you put on it and in it. Maxine saw no reason to force terrible food on the stomach merely because it was

suspended thirty-five thousand feet above sea level; all the other first-class passengers from Paris had munched their way through six overcooked courses, but Maxine had merely accepted a little

caviar (no toast) and only one glass of champagne (nonvintage, but Moët, she observed with approval before accepting it). From a burgundy suede tote bag she had then produced a small white

plastic box that contained a small silver spoon, a pot of homemade yogurt and a large, juicy peach from her own hothouse.

Afterward, while other passengers had read or dozed, Maxine had taken out her miniature tape recorder, her tiny gold pencil, and a large, cheap office duplicate book. The tape recorder was for

instructions to her secretary, the office duplicate book was for notes, drafts and memos of telephone conversations; Maxine tore them off and sent them on their way, always retaining a copy of what

she had written; then when she returned to France, her secretary filed the duplicates. Maxine was well organised in an unobtrusive way; she didn’t believe in being

too

well organised

and she couldn’t stand bustle or hustle, but she could only operate when things were orderly; she liked order even more than she liked comfort.

When Madame la Comtesse booked a reservation for a business trip, the Plaza automatically booked a bilingual secretary for her. She sometimes travelled with her own secretary, but it was not

always convenient to have the girl hanging round one’s neck like a pair of skates. Also, as the girl had now been with Maxine for almost twenty-five years, she was able to keep an eye on

things at home in Maxine’s absence; from the condition of her sons and her grapes to the times when Monsieur le Comte returned home and with whom.

Mademoiselle Janine reported everything with devoted zeal. Since 1956, Mademoiselle Janine had worked hard for the Château de Chazalle and she shone in the reflected glory of

Maxine’s success. She had first worked for the de Chazalles twenty-two years ago, when Maxine was twenty-five and had opened the château as a historical hotel, museum and amusement

park, before anybody (except the locals) had heard of de Chazalle champagne. Mademoiselle Janine had fussed around Maxine from the time her three sons were babies, and she would have found life

intolerably dull without the family. Indeed, she had been with the de Chazalles for so long that she almost

felt

like one of the family. But not quite. They were—and always would

be—separated by the invisible, unbreakable barriers of class.

Like New York, Maxine was glamorous and efficient, which was why she liked the quick pace of the city, liked the way that New Yorkers worked with neat, brisk speed whether they were serving

hamburgers, heaving garbage off the sidewalk or squeezing fifty cents’ worth of fresh orange juice for you on a sunny street corner. She appreciated these fast-thinking people, their tough

humour, their crisp jokes, and privately thought that New Yorkers had all the

joie de vivre

of the French, without being nearly so rude. She also felt at home with New York women. She

enjoyed observing, as if they were another species, those cool, polite, impeccable women executives as they operated under the merciless pressure of the grab for power, the lunge for money, the

lusting after someone else’s job. Like theirs, Maxine’s self-discipline was colossal, but—at the age of forty-seven—her grasp of people-politics was even better. Had it not

been so, she would not have been travelling to meet Lili.