Lamplighter (4 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

“Fire!” Grindrod hollered, and the prentice-watch let go a clattering volley at the beast. It gave voice to a disturbing, sheeplike bleat and ceased its struggling.

Still the calendar bane held the other two beasts in a prison unseen while a pistoleer pulled herself from the ruin of the transport. She drew forth two long-barreled pistolas and fired both point-blank into the glimmering, helpless eyes of one of the pinioned creatures.With a violent jerk and gouts of black pouring from its head, the beast expired.

All that remained was the largest monster. A tortured thing it was now, twisting and thrashing upon the ground, a captive of its own agony. The woman never moved, never touched it, a hand always at her temple. Slowly the creature’s movements slackened; slowly its writhings turned to twitchings and finally to nothing. Its terrifying orange eyes faded and at last were extinguished.

With an audible and weary exhalation, the calendar bane sagged to the ground.

Rossamünd let out a quiet relieved sigh of his own.

“Ye’ve done it, lads!” Grindrod exclaimed, proud and a little amazed. “Ye’ve just won through yer first theroscade.”

It’s not my first,

Rossamünd thought but kept to himself.

Rossamünd thought but kept to himself.

“There’ll be punctings for ye all after this tonight,” the lamplighter-sergeant continued.

“It’s been a prodigious long time since a prentice was marked,” Bellicos chipped in.

The prentices grinned at each other weakly, happy simply to be alive.

I don’t want to be puncted!

Rossamünd fretted.

Rossamünd fretted.

Grindrod turned to him. “Ye’re carrying the salt-bag, Master Lately.Ye can come with me,” he declared.

Leaving the lampsmen to organize the prentices into piquets, the lamplighter-sergeant stalked over to the wreck of the park-drag. The calendar bane and pistoleer were bent over one of their fallen while the long-haired wit sat slumped in the twigs and dirt by the bristled corpse of a dead nicker.

“The sniveling snot—almost ruined us all with her wanton wit’s pranks,” Grindrod cursed under his breath, then called as they approached, “Hoi, calendars! Bravely fought and well won, m’ladies! Lamplighter-Sergeant Grindrod and a prentice come to offer what aid we might.”

Crouched by the body of her comrade whose face was a gory mess, the bane looked up at him. Her cheeks and brow glistened with a lustrous patina of sweat; her eyes were sunken and her skin was flushed. Rossamünd thought she looked more ill than injured. “We may have triumphed in the fight, but the loss of two sisters is never well,” she returned in a soft voice, with a hint of a musical southern accent. “Lady Dolours you may call me, Lamplighter-Sergeant; bane and laude to the Lady Vey, esteemed august of the Right of the Pacific Dove.Your assistance is welcome. My sister languishes with these terrible bites to her face but will survive if attended to quickly. I would tend her myself, but I lack the right scripts. Do you carry staunches? Vigorants?” All this time she had not stood, and the effort of speaking left her breathless.

Keen to please, Rossamünd nodded eagerly. “Lamplighter-Sergeant, I have what she requires,” he said emphatically as he fossicked about in the potive satchel. “Thrombis and a jar of bellpomash.” The first would stop a wound’s flowing and the second revive spirits when taken in food or drink.

“As it should be, prentice.” Grindrod nodded curt approval. “Ye may give them what they need.”

Rossamünd held the jars of potives as the pistoleer ministered to the gruesome injuries on her sister’s face. He forced himself to keep watching, to not flinch and wince and look away from the gore: he was no use to anyone if he let others’ wounds trouble him. With a fright he saw a flash on the edge of his sight, and was startled by a

Crack!

as Bellicos put his fusil to the head of a prostrate nicker and brought its twitching throes to an end.

Crack!

as Bellicos put his fusil to the head of a prostrate nicker and brought its twitching throes to an end.

“I must ask ye, lady maiden-fraught, what possessed ye to be traveling in the eve of a day with a six-horse team?” Grindrod folded his arms. “Ye ought to know it only encourages the bogles!”

The diminutive calendar called Dolours looked the lamplighter-sergeant up and down as if he were a block-headed simpleton. “That I do,” she returned wearily, “as does even the least schooled. The horses were proofed in shabraques, sir, and doused with the best nullodors we possess; and had we been allowed a night’s succor by your less-than-cheerful brothers at Wellnigh, we would not have needed to venture forth so foolishly in the unkind hours.” She held the sergeant-lighter’s stare. “But we were refused lodging at that cot, directly and to our faces. No room for a six-horse team, or so they said.”

“That can’t be right.” Grindrod scowled. “Of course six horses can stable in Wellnigh—wouldn’t be much use if they couldn’t! What other reason did they give?”

“No other reason at all, Lamplighter-Sergeant,” the bane said coolly. “After this first exchange the charming Major-of-House himself simply refused entry and sent us on our way. Little less than storming the twin keeps would have got us within.”

“Bah!” Grindrod almost spat. “Another of the Master-of-Clerks’ spat-licking toadies,” he muttered. Aloud he said, “He’s one of the new lot shifted up from the Considine. If what ye say be true, I’ll be having words with the Lamplighter-Marshal—refusing folks bain’t the way we conduct ourselves out here on the Emperor’s Highroad. Succor to all and a light to their path,” he concluded, with one of the many maxims with which the prentices had been indoctrinated from the very first day of prenticing.

“A light to your path,” intoned the prentices automatically, as they had been taught.

“Indeed, Lamplighter-Sergeant,” Dolours returned, “the Emperor’s lampsmen seem not to be what they once were.”

Grindrod bridled.

Rossamünd too felt a twinge of loyal offense.The lampsmen he had come to know worked hard to keep the roads lit and well tended.

“Attacks rise and numbers dwindle, madam,” the lamplighter-sergeant countered, chin lifted in defensive pride, “yet the road has the same figure of lamps and still we have to compass it all. So I ask again: what be yer business on the road?”

The calendar stayed her ground. “As I understand it,” she said slowly, “time is running short for your prentices to be sufficiently learned in their trade, true?”

“Aye, precious short. What of that?”

“It’s a simple thing, you see,” Dolours said, ever so quietly. She looked to the long-haired calendar—Threnody, they had called her—who glared at both the lamplighter-sergeant and Rossamünd. “This young lady desires to become a lamplighter.”

2

WINGS OF A DOVE

fodicar(s)

(noun) also lantern-crook, lamp- or lantern-switch, poke-pole or just poke; the instrument of the lamplighter, a long iron pole with a perpendicular crank-hook protruding from one end, used to activate the seltzer lamps that illuminate many of the Empire’s important roads. The pike-head allows the fodicar to be employed as a weapon—a kind of halberd—to fend off man and monster alike.

(noun) also lantern-crook, lamp- or lantern-switch, poke-pole or just poke; the instrument of the lamplighter, a long iron pole with a perpendicular crank-hook protruding from one end, used to activate the seltzer lamps that illuminate many of the Empire’s important roads. The pike-head allows the fodicar to be employed as a weapon—a kind of halberd—to fend off man and monster alike.

F

ROM the little Rossamünd knew of these things, lamplighters rarely, if ever, employed women as lampsmen. As servants, as cothouse clerks, or even as soldiers maybe, but never a lighter.

ROM the little Rossamünd knew of these things, lamplighters rarely, if ever, employed women as lampsmen. As servants, as cothouse clerks, or even as soldiers maybe, but never a lighter.

Lamplighter-Sergeant Grindrod puffed his cheeks, his jaw jutting stubbornly. “Her?” Then he laughed—a loud, foolish noise in the mourning-quiet after the attack. “She near brought us all to ruin. She’ll be lucky I don’t clap her in the pillory for impeding the goodly duties of His Rightful Emperor’s servants!”

Threnody stood, clench-fisted. “I am a peer, you lowborn toadlet, of rank so far above yours, you’ll be lucky I don’t claim quo gratia and have you clapped in irons yourself, you sot-headed dottard!”

Rossamünd tried to pull his neck into his stock as a turtle might.

His fellow lighters gathered near, awestruck.

The lamplighter-sergeant was agog. “Lowborn? Sot-headed? Quo gratia?” Grindrod’s red face became an apoplectic purple. “I’m not the want-wit who frissioned my watch to a daze in the middle of a bogle attack! They wasted the surgeon’s fees on ye, poppet!”

Threnody let out a tight, wordless yell, both her hands clutching her temple.

Rossamünd’s head, his entire gall, revolted, and his sense of up and down collided. He staggered and fell, joining Grindrod, the lampsmen, the prentices and even the pistoleer writhing in the dirt.

“Enough!”

cried Dolours, and the wayward frission ceased. The bane was the only one standing, her left hand to her temple, her right stretched over the now prone Threnody. She had witted the girl, striven one of her own. “Enough,” she whispered again. Looking deeply unwell, she reached a conciliatory hand to Grindrod regardless, an offer of help.

cried Dolours, and the wayward frission ceased. The bane was the only one standing, her left hand to her temple, her right stretched over the now prone Threnody. She had witted the girl, striven one of her own. “Enough,” she whispered again. Looking deeply unwell, she reached a conciliatory hand to Grindrod regardless, an offer of help.

“I can get to me feet meself, madam,” he seethed, tottering dazedly as he proved his words.

As Rossamünd and his fellows unsteadily regained their feet, Dolours sighed. “That ‘poppet,’ Sergeant, is the daughter of our august and a marchioness-in-waiting in her own right: you’d do well to pay your due respect.”

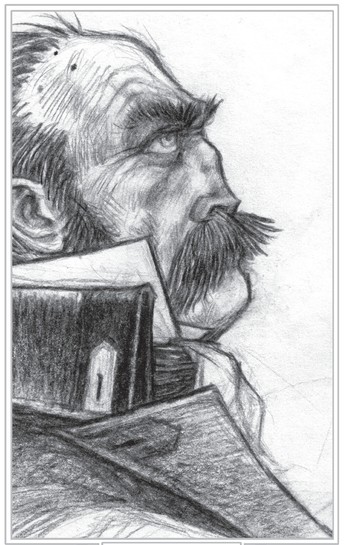

LAMPLIGHTER-SERGEANT GRINDROD

Lampsmen Bellicos, Puttinger and Assimus muttered grimly.

The prentice-lighters looked to their sergeant.

“And a great liability she’d be to ye too, I am sure.” Grindrod smiled. He nodded a bow, saying louder, “I apologize to ye.” He wrestled with himself a moment, then with deliberate, frosty calm added, “I don’t know where such a custard-headed notion sprang from, madam, but women bain’t wanted in the lighters!”

“We know it well, Lamplighter-Sergeant!” The calendar bane stood unsteadily and Rossamünd saw her face turn a ghastly gray. Clearly she suffered from some feverish malady. She smiled sadly. “Perhaps you are right, but yet it is not an impossible thing for a woman to take her place in your quartos, I am sure?”

Grindrod’s mustachios bristled and writhed as he considered her words. “Bain’t really for me to say one way or t’other, bane,” he said finally. “This shall have to be the decision of the Lamplighter-Marshal.”

“Hence our journey to Winstermill, Lamplighter-Sergeant,” Dolours countered.

“Well, our work tonight takes us in the contrary direction.” Grindrod rocked back on his heels, his arms still folded across his broad chest. “However, I’ll send back a transport with guard to gather the fallen and bring ye all back to Wellnigh. Now ye’re six horses less they’ll be having to give ye a billet, I reckon.” With that, the lamplighter-sergeant pivoted on his brightly polished heel and stepped out on to the road, calling the prentices and lampsmen to him.

Sick with too much frission, Rossamünd came tumbling after, trying hard not to trip over the putrid bodies of the dead bogles. The lamplighter-sergeant made hasty arrangements: he and Bellicos and the other prentices would continue on to Wellnigh House, the sturdy little cottage-fortress to the east, continuing to light the remaining lanterns as they went. Rossamünd, however, as possessor of the salumanticum, was to be left behind to tend the calendars’ wounds. With him would remain Lampsmen Assimus and Puttinger as a nominal guard and fatigue party to help with the fallen and to salvage the luggage.

With a cry of, “Prentice-watch in single file, by the left, march!” Lamplighter-Sergeant Grindrod, Lampsman 1st Class Bellicos and the wide-eyed, nervous prentices went on, leaving Rossamünd and the other two lampsmen with the vigilant, silent calendars.

Assimus and Puttinger ignored Rossamünd. Lampsmen rarely shared in chitter-chatter with prentices till they were full lampsmen themselves. Reluctantly they set to work finding belongings and goods amid the shatters and splinters, making a pile of the broken trunks and half-rent valises. Typical of the older men who worked on this easy stretch of road, they were crotchety half-pay pokers whose job was to babysit the lantern-sticks out on the road as they learned their trade. They paid no attention whatsoever to the lads unless duty demanded.

Other books

Least of Evils by J.M. Gregson

School of Discipline by John Simpson

An Exchange of Hostages by Susan R. Matthews

Where You Can Find Me by Cole, Fiona

Plea of Insanity by Jilliane Hoffman

Mason: A Manchester Bad Boys Romance by Foxworth, Lena

Founding America: Documents from the Revolution to the Bill of Rights by Jack N. Rakove (editor)

Diary of a Madman and Other Stories by Nikolai Gogol

TheAngryDoveAndTheAssassin by Stephani Hecht

The Monster of Shiversands Cove by Emma Fischel