Lamplighter (55 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

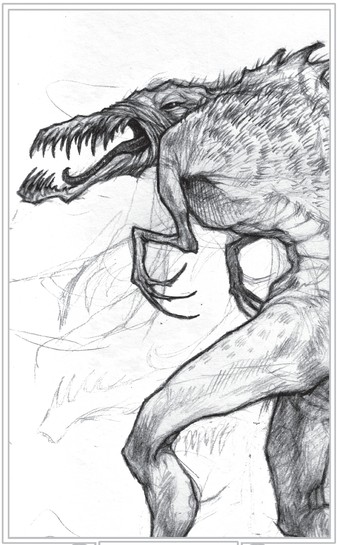

WORMSTOOL BRODCHIN

It was too much now—the bogles had had enough. They were quitting the fight, running back up the Wormway and off into the wilderness. Not satisfied, Threnody trod determinedly toward the cothouse, striving at the monsters inside. Still flailing in fury at the slobberer as it struggled to rise, Rossamünd was vaguely aware that lumpy bogles were fleeing the tower: one even leaped from the roof, landing with a mighty crash in some bushes and, yipping girlishly, disappeared into the scrub. With their escape, the malice of the threwd flared strong for a moment then subsided, leaving only confused watchfulness.

Rossamünd kept hitting, and only when he had smote the utter ruin of the stomping, slobbering nicker did he cease. He stared down at the shattered, mangled creature at his feet: somehow it still lived, glaring up at him, still defiant, still baleful, still hungry.Yet now Rossamünd could not hate the fiendly thing, no matter what it had done to the doughty, friendly lighters of Wormstool. Now he just felt tired and sorry: sorry for the death of his comrades; sorry for the harm he had done the monster before him, to all the monsters; sorry that

he

had become the murderer, the hypocrite.

he

had become the murderer, the hypocrite.

“I am sorry to have slain thee,” he whispered, little knowing from where the words came. “But we were at odds and I could not let you hurt my friends.”

The creature’s eyes glazed, a sadness—an ancient longing—seeming to dwell in them for a moment, and it ceased.

Gory fodicar still in hand, Rossamünd dropped to his knees and wept.

“Surely you don’t weep over the monsters!” he heard Threnody croak as she picked up her doglocks, still lying where she had discarded them. She sat exhausted on the road and thirstily downed a milky blue liquid.

Rossamünd doubled over, keening agony in his very depths. He felt a subtle touch on his lantern-crook. Looking up, he saw that same familiar sparrow perched on the bunting-hook. It gave a single firm chirp as if it were chiding him, and whirred away.

“Oh, go away!” Threnody shied the empty alembant bottle at the departing bird. “A fat lot of good you did for us just now! Go back to your master and tell him the happy news!”

“Threnody!” Rossamünd cried as the flask missed well wide and disappeared into the thistles below.

In her sudden fury the girl turned on him, and for a moment he thought she might throw something at him too. But she did not.

Rossamünd stood, leaning on his fodicar as if it were a geriatric’s cane.

Though smoke was billowing from the upper stories and carrion crows were already perching upon the chimney pots, Rossamünd and Threnody still walked to it and climbed to the front door, stepping with heavy grief over the body on the steps. It was Theudas. In the watch room the doors to the cellars had been torn from hinges and cast aside.The collapsible stair, now nothing more than a wreckage of timbers, had worked perfectly; yet this had not been enough to stop the murderous nickers from gaining the higher floors. It was, however, more than adequate in preventing the two survivors from getting above.They called out, screamed and screeched till they were hoarse, hoping to hear the answering plaints of a survivor from the upper levels. But no such answers came, only the hiss and crack of fire unchecked.

Together the two hastily scrounged whatever they could from the litter—food parcels and water skins found in the cellars and with them a flammagon. Among the ruination they discovered the inert white mass of Sequecious, bloodied and cold, collapsed across an equally fat, bilious-looking bogle with great bloodred fangs. It too was dead, the boltarde that slew it still clutched by Sequecious, the aspis-smeared blade thrust full through its ribs, scorch marks showing that it had received the blast of a firelock. Man and monster had died together.Whelpmoon lay faceup by his squat lectern, his glasses missing, his dead eyes staring. By the kennels the dogs had managed to destroy a brace of scaly, big-nosed bogles, perishing themselves as they did.

Men and dogs and monsters, everything was dead. Rossamünd could only imagine the gore and carnage on the floors above.

Too much . . . too much . . .

His extremities began tingling, and just as his anguish became overwhelming it was quickly obscured by a weird, empty flatness.

Too much . . . too much . . .

His extremities began tingling, and just as his anguish became overwhelming it was quickly obscured by a weird, empty flatness.

A terrible smashing report thundered from the floors above and shook the fortalice.

“We must go,” Threnody insisted, standing at the top of the cellar steps.

Back down on the road, the two survivors tried to bring Rabbit with them, but the loyal, stupid beast would not leave his friend and master. Flat cart still hitched, it had slowly followed them and now stood forlornly by Splinteazle’s remains and would not move. Not even a sprig of swamp oak could induce it to come away.The two young lighters would have had to drag it every single step to get the beast to Bleak Lynche, and they might have done but were desperate to be gone. So they unhitched the cart and left the faithful donkey standing at the base of the tower, ears down, head down, nosing the seltzerman’s cooling corpse.

“What a waste,” Threnody spat, venting her angry grief as they fled. “It’s idiotic. Even out here, with hardly anyone to benefit, they still go on risking lives to light the lamps each evening and douse them each dawning. No one in the cities cares—not even in the towns around about are people mindful or grateful.Whoever uses this part of road? The Bleaksmen stay put. That place is nothing more than a cothouse with a fistful of desperadoes setting up shop about it—what’s the point? Imperial waste!” She gagged back a sob.

“But if they did not make a stand here everyone west would suffer!” Rossamünd’s contradiction was reflexive, yet in truth he actually agreed with her.

“Do you really think the flimsy string they call the Wormway, with its few tottering towers so close to the Gluepot and the tired quartos that habit them, is a match for the gathered might of the monsters? Look how easy it was for a small band of brodchin to annihilate one cothouse. It’s the work of my sisters that keeps your precious western folk safe!”

Rossamünd had no answer for this—he just wanted to get to somewhere secure. He found himself hoping Mama Lieger might shuffle from the scrub and lend them aid.

How can she have let this happen? Did

she

cause all this?Was the threwd of the land itself the culprit? Is that what I felt?

How can she have let this happen? Did

she

cause all this?Was the threwd of the land itself the culprit? Is that what I felt?

An almighty shattering boom roared behind them, scaring them so much they both let out a yelp.They looked back to see the shingle roof of the cothouse collapsing inward with a seething eruption of smoke, sparks jetting from the shell of the tower. Rossamünd spied a hasty little shadow scuttling after them.

Freckle?

Walking on, Rossamünd ached to speak with the glamgorn, to ask question after question, but most of all—why? Why were they attacked? Why did the glamgorn not help? Why was he still following him? However, with Threnody by Rossamünd’s side, Freckle would never come near. Strangely, irrationally, the young prentice felt safer with Freckle at their backs.

The day grew darker still and, as poor dead Splinteazle had predicted, it began to rain. Monsterlike shapes seemed to lurk and lunge in the gloom, phantasms made by the rapid fall of water.

At least I have my hat,

Rossamünd thought bitterly.

At least I have my hat,

Rossamünd thought bitterly.

A far-off cry—a shriek and a gabber—came from somewhere out on the flatland. It was an inhuman call, a monster’s voice. Rossamünd cringed at the noise and almost tripped, expecting any moment to be waylaid again. Though they were exhausted, desperation and blank terror set the two lighters running, a weary stumbling lurch, each helping the other if ever one flagged.

When the glimmer of the lights of Bleak Lynche hove in sight, Rossamünd eagerly took up the flammagon and shot its spluttering pink fire into the air. The flare drew a high, lazy arc, the falling damps carrying it northward. It winked out as it fell on the downside of its curve. They had little hope of it attracting attention, yet it did: a ten-strong foray of the Bleakhall day-watch.

The band of lighters that found them could little believe what they were told: a whole cothouse slaughtered? Surely not! Several lampsmen gave shouts of lament. Scrutineers were sent to Wormstool, the sneakiest of the band, while Rossamünd and Threnody were hustled back to Bleakhall. There the astounded Fortunatus the house-major conducted a hasty inquiry. He kept asking the same questions: “What happened? Where are the other lampsmen? How is it just you two survived?”

Rossamünd did not know how to answer except with the truth.

Fortunatus could not accept their shocking tale until the piquet of scrutineers returned, dragging Rabbit, braying mournfully, with them. These doughty fellows confirmed the blackest truth: a whole cothouse slaughtered; friends torn and all dead, the ransacked fortlet open to the elements. They brought with them body parts and several bruicles of cruor as proof, and offered one of these to the two survivors. “So ye might mark yeselfs proudly!” they said.

Rossamünd refused. The handing out of awards at such a time seemed so wrong to him—ill-timed and disrespectful. It did not occur to him that his feats would warrant a marking, maybe even four according to the grisly count that revolved ceaselessly in his mind.

“Not want a mark?” was the general, incredulous reaction. “That ain’t natural!” But they did not press him.

Threnody, however, gladly received the blood, and this was a great satisfaction to the other lighters. “My first cruorpunxis,” she murmured, scrutinizing the bruicle closely. Either way, all agreed that Grindrod must have improved greatly in his teaching of prentices to raise such doughty young lighters.

27

A LIGHT TO YOUR PATH

obsequy

what we would call a funeral, also known as a funery or inurment. These rites typically include a declaration of the person’s merit and then some traditional farewell given by the mourners. In the Haacobin Empire it is most commonly thought that when people die they simply stop: a life begins, a life ends. In the cultures about them and in their own past there have been various beliefs about afterlife and some all-creating elemental personage, but such notions are considered oppressive and outmoded. They would rather leave these ideas to the eekers, pistins (believers in a God) and other odd fringe-dwellers.

what we would call a funeral, also known as a funery or inurment. These rites typically include a declaration of the person’s merit and then some traditional farewell given by the mourners. In the Haacobin Empire it is most commonly thought that when people die they simply stop: a life begins, a life ends. In the cultures about them and in their own past there have been various beliefs about afterlife and some all-creating elemental personage, but such notions are considered oppressive and outmoded. They would rather leave these ideas to the eekers, pistins (believers in a God) and other odd fringe-dwellers.

G

IVEN his own room in the Fend & Fodicar and saloop spiked with a healthy dose of bellpomash, Rossamünd slept two days through after the attack, while outside the rain became a fierce storming downpour. He did not know till he had woken again that a dispatch had been sent to Winstermill informing them of the terrible things done at Wormstool and of the two young survivors. Neither was he aware that the loss of that cothouse had occasioned the temporary suspension of lamplighting along the entire twenty-five-mile stretch of highroad between Bleak Lynche and Haltmire. Nor did he know that Europe had returned from a course while he slept and after a brief inquiry into his health, left again, quick on the trail of the surviving nickers. How the young lighter wished she had been with them at Wormstool; what lives might have been spared with the Branden Rose at the task.

IVEN his own room in the Fend & Fodicar and saloop spiked with a healthy dose of bellpomash, Rossamünd slept two days through after the attack, while outside the rain became a fierce storming downpour. He did not know till he had woken again that a dispatch had been sent to Winstermill informing them of the terrible things done at Wormstool and of the two young survivors. Neither was he aware that the loss of that cothouse had occasioned the temporary suspension of lamplighting along the entire twenty-five-mile stretch of highroad between Bleak Lynche and Haltmire. Nor did he know that Europe had returned from a course while he slept and after a brief inquiry into his health, left again, quick on the trail of the surviving nickers. How the young lighter wished she had been with them at Wormstool; what lives might have been spared with the Branden Rose at the task.

As he slowly awoke, eyes heavy and senses murky, Rossamünd was gradually cognizant of a figure looming at his side. In fright his senses became sharp and he sat up swiftly, pivoting on his hands ready to jump, to run, to shout red-screaming murder. With clarity came truth and with truth came the profoundest delight. It was Aubergene—his old billet-mate—sitting by Rossamünd’s recovery-bed on an old high-backed chair, dozing now as if he had been waiting at the bedside a goodly while. Even as Aubergene’s presence fully dawned on Rossamünd, the older lighter snorted awake.

“Aubergene!” Rossamünd exclaimed. “Aubergene!”

“Ah, little Haroldus.” The older lighter grinned, though sadness lurked at the nervous edges of his gaze. “Dead-happy news to find you and the pretty lass hale! I’ve heard from the house-major here how you won through. A mighty feat for young lighters.”

Other books

The Space In Between by Cherry, Brittainy

The Didymus Contingency by Jeremy Robinson

The Lifeboat Clique by Kathy Parks

Naughty in Nottinghamshire 02 - The Rogue Returns by Leigh LaValle

Forever Friends by Lynne Hinton

The Life and Prayers of Saint Paul the Apostle by Wyatt North

Lines We Forget by J.E. Warren

Warzone: Nemesis: A Novel of Mars by Graham, Morris

Hotel Living by Ioannis Pappos

George Washington Zombie Slayer by Wiles, David