Land of Unreason (2 page)

Authors: L. Sprague de Camp,Fletcher Pratt

Oh, for heaven's

sake! Why couldn't they let up? Why couldn't anybody let up? If he had been

more sure of Kaja, of where she might be spending that night when the bombers

came, he wouldn't have run out of the Embassy. If he could be more sure of Kaja

now, he wouldn't be miserable. He allowed his mind to dwell on Kaja, pleasant

thought, her red hair and long silky legs, and the fact that although she had a

straight nose and Hungarian name and claimed to be from Budapest, she was

unquestionably Jewish.

Kaja, pleasant thought,

always looking light enough to fly. The fragment of a song occurred to

him—"I wonder who's kissing her now"—and he smiled wryly. Anybody who

could buy her enough Scotch. Kaja preferred Scotch to champagne. It was a good

drink, Scotch. Useful when a man couldn't sleep.

He got up, more slowly this

time, and dug out his bottle of Scotch, pouring himself a hefty dram. He

swashed it around in the glass, staring at the pale-orange liquid. Useful

stuff, but only up to a limit. What was his limit? The limit of a diplomatic

career which had already reached its limit when he fed horse meat to the

Congressman. Oh, damn! Oh, hell! It might have been all right but for this war,

might have been forgotten if foreign affairs had not become so tense that every

member of the service was forced, so to speak, to operate in a show window,

with his name constantly under Congressional scrutiny. And Kaja ... ? He lifted

the glass.

Beroom.

And set it down

again. With a trick of automatic memory his mind had jerked back to the picture

of Mrs. Gurton going out the back door. She had had something in her hand, a

bowl, a bowl of ... milk. Milk? The Gurtons didn't keep a cat. Why milk to the

back door?

Fred Barber remembered that

Mrs. Gurton had said this was St. John's Eve, the twenty-third of June, the day

before Midsummer Day. Oh, yes, something in

The Golden Bough.

You leave

milk out for the Little People that night, especially if there is a baby in the

house, for unless the Little People receive their tribute they are likely to

steal the child and leave a changeling. Interesting survival; who would have

believed that a woman whose husband ran a drill press in a munitions factory

and who herself went to nurse a neighbor through a bomb wound, would leave milk

at the door for fairies? Almost worth writing a sardonic little note about, to

be sent to the

New Yorker

which would return him a check no doubt, to be

spent on Scotch for Kaja.

Milk.

Fred Barber liked milk, a

fact which he concealed with the most painful care from the gay, interesting,

mocking crowd in London. He had been brought up on a drink of milk before

bedtime. It made him sleep. But the war and milk rationing had made him go

without, like many others to whom milk was more of a hobby than a necessity.

Mrs. Gurton could have it for the baby of course. But if she were going to give

it to the fairies, why, Fred Barber argued to himself with a grin, he was as

good a fairy as any who would be abroad that night. The mission of fairies was

to bring gifts and he was bringing the Gurtons a pound sterling a week.

Milk. The mere idea of

drinking it instead of the Scotch gave him a sense of virtue and power. What

was it Nietzsche had said: "Every conquest is the result of courage, of

hardness towards one's self"? Well, he would conquer, in spite of the

crack on the head. His mind flashed back to the determination with which he had

set out on his career. If he could recover some of that, the old pep, a little

crack on the head wouldn't matter. He could demonstrate a capacity for hardness

to himself, recall the sense of destiny that had filled him once. To hell with

the Scotch, and Kaja too. He strode to the door, his mind so intent on the

peculiar nobleness of using milk instead of Scotch as a sleeping powder that he

carried the glass with him.

The moonlight showed the

bowl, sure enough, a pale circle beside one of the flowerpots that lined the

back of the cottage. Barber stuck his finger in the bowl and tasted. It was

milk—trust Mrs. Gurton. He set down the glass, and as the bombs in the distance

continued their infernal beat, lifted the bowl in both hands, drinking slowly

and with relish.

Over the edge of the vessel

he could see the red glow that marked something burning in Bradford, with searchlight

beams flickering cobwebby above. And what would the fairies of St. John's Eve

do now, poor things, with no milk, and bombs falling on their heads? Fred

Barber set the bowl down, and then grinned like a small boy in the dark as

inspiration came to him. They could drink Scotch!

He poured the slug of Scotch

into the bowl, watching the last dregs of the milk weave through it, and

chuckled at the thought of Mrs. Gurton's expression when she found the milk of

which she had robbed the baby so mysteriously transmuted. The delicious sense

of languor in every limb that presaged instant slumber was still wanting, as it

had been ever since his injury, but he knew now it would come, he was at peace.

The trouble with these

English feather beds, though, was not merely that they were too warm for the

twenty-third of June, but also that you went right on down through the softness

till you hit a bump. There was one under his hip and he shifted position to

avoid it. Wonderful people, these English— His carefully cultivated cynicism

broke down when he contemplated them. Fairies and machine shops and courage

under bombings—like something out of a poem by Walter de la Mare. Or Masefield.

Yes, especially Masefield.

His mind swung lazily into

contemplation of the essential Tightness of choosing Masefield as the poet

laureate of this people, for whom he wished he could do something—then drifted

into a hazy picture of Masefield characters, all mingled with fairies, Kaja and

the Gurtons. He came to with a start, realizing that he had almost been asleep.

Without regrets, he drifted into a blankness of thoughts half formed ...

Tik.

The door hinge,

faintly, as though someone had moved the door through a few minutes of arc.

Then again—tik—tik—tik, tik tik, tiktiktik.

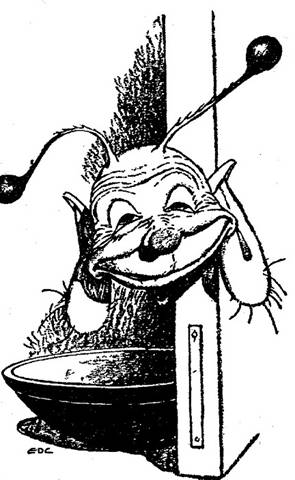

Barber, fully awake now,

looked toward the door. It was open, and something coming through it. He

couldn't be sure in the gloom, but it looked like a face, an incredible face

that might have come from a comic strip. The loose lips were drawn back in a

grin so extended that the corners of the mouth were out of sight. For all

Barber could tell the grin went all the way round and met at the back, like

Humpty Dumpty's. The ears were pendulous; over the grin was a head utterly

hairless but bearing a pair of knobbed antennae.

Oh, well,

that,

said

Fred Barber to himself, and with that strange double vision, outside and inside

of one's personality, that comes at the edge of sleep, felt certain he was

dreaming and slipped down into the blank again.

-

II

He was lying on his side,

one arm curled under his head and blue moonlight all around him. Bright

moonlight: one could read newsprint in such an illumination, he reflected in

the first half second of returning consciousness, and then write to Ripley about

it. Somewhere in the "Believe It or Not" collections was the

statement that the feat was impossible. If ...

He became aware that the

fingers of the hand underneath were touching grass and heaved himself to a

sitting posture, now bolt wide-awake. From beyond his own feet the face of the

dream was grinning under knobbed antennae, which pricked eagerly toward him

like the horns of a snail. Behind, Barber was conscious of other crowding

figures as he tried to concentrate on what Knob-horns was saying.

"... mickle bit o'

work, moom." Knob-horns spread arms and let the hands dangle from a pair

of loose wrists, slightly swaying like a tight-rope walker. " 'E were that

'eavy.

'ic."

There was a

little ripple of suppressed amusement behind Barber, with a clear contralto

voice rising out of it:

"Wittold! Is't so you

were taught to address the Queen's Majesty? What said you?"

The mobile features

regrouped themselves from a grin into an expression of comic and formidable

sullen-ness.

"I said 'e were

'eavy."

"Aye. One needs not

your ass's ears to have caught so much. But after that?"

Barber swiveled. The

contralto belonged to a beauty, built on the ample lines of a show-girl chorus

he had once seen, justifiably advertised as the "Ten Titanic

Swede-hearts." He caught a glimpse of patrician nose, masterful chin, dark

hair on which rode a diadem with a glowing crescent in front.

The being with the antennae

replied: "I said nowt after that,

'ic."

Barber

experienced the odd sensation of being informed by some sixth sense that the

individual was not quite sure of his own veracity. The tall lady had no such

doubts:

"Ah, 'tis time for a

shaping, indeed," she cried, "when my husband makes messengers of

louts that lie barefaced! What is't, I asked, some new form of address in mock

compliment from my gentle lord? You said

Ic!"

Antennae shifted

his feet, opened his mouth and abruptly fell down. The others clustered around

him, twittering, babbling and pushing, a singular crowd.

Some were as tall as Barber,

and some small, down to a foot in height, and their appearance was as various

as their size. Many, especially of the smaller ones, had wings growing out of

their backs; some were squat and broad, as though a gigantic hand had pushed

them groundward while they were in a semi-fluid state. An individual with a

beard and wall eyes that gave him an expression of perpetual surprise was

dressed like a Palmer Cox brownie; others wore elaborate clothes that might

have been thought up by King Richard II, and some had no more clothes than a

billiard ball.

Pink elephants, thought

Barber, or am I going nuts? One half of his mind was rather surprised to find

the other considering the question with complete detachment.

"What ails yon wight?"

demanded the regal lady, who had not condescended to join the crowd.

The brownie looked around.

"A sleeps; plain insensible like a stockfish, and snoring." There was

a chatter o£ other voices: "An enchantment, for sure— Send for Dos Erigu

... The leprechauns again, they followed the king ... Nay, that's no prank,

'tis sheer black kobbold malice ..."

"Peace!" The

contralto cut sharply across the other voices, and she extended her arm. Barber

saw that she held a slender rod about a foot long, with a point of light at its

tip. "If there's sorcery here we'll soon have it unsorcelled.

Azam-mancestu-monejalma—sto!" The point of light leaped from the tip of

the rod, and moved through the air with a sinuous, flowing motion. It lit on

the forehead of the antennaed one, where it spread across his features till

they seemed to glow from within. He grunted and turned over, a fatuous smile

spreading across his face, but did not wake. The tall lady let arm and rod

fall.